Mapping the Effects of Parking Minimums

Today we welcome friend of Strong Towns, Joshua McCarty, who works at Urban Three. He’s sharing some incredible and illuminating maps created by Urban Three that show the disastrous effect of parking on our cities.

What makes surface parking so destructive is that it consumes a finite resource with virtually no direct financial benefit. Our pre-occupation at Urban Three is local finance. From that perspective, parking--in particular the vast kind that adorns strip malls and box stores--is dead weight. Local governments, be they in cities, towns, or counties, are all constrained by the land they can develop. What they do with that resource is thus, paramount to how well they can pay their bills. Tax revenue is but one of many resources squandered by each acre of land devoted to deactivated cars.

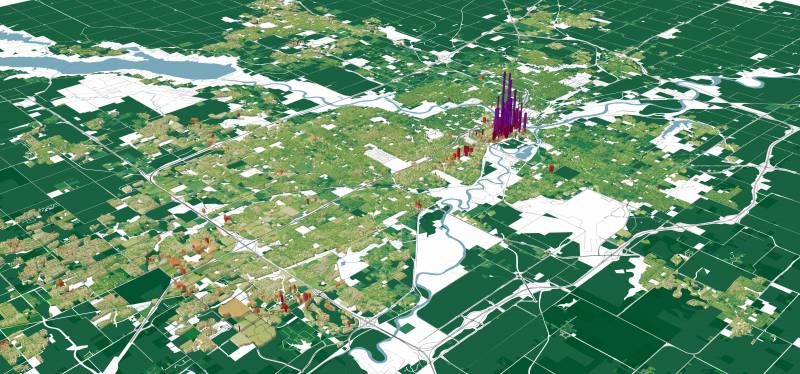

This year for #BlackFridayParking, I’ll delve deeper into the pattern of tax efficiency in our 3D models to focus on the impact of surface parking. Those of you who are familiar with Urban Three will recognize this image as the incredibly common pattern of property tax production per acre:

What’s fascinating about this model is that, without knowing the city or county, having no idea what the underlying development looks like, it’s nearly impossible not to find downtown. (It's Des Moines, by the way.) Smaller satellite downtowns, new urban developments, and historic districts are similarly easy to find. What’s more difficult is to find the more typical symbols of economic development. Can you find any of the three major shopping malls in this model? The vast office park headquarters of Wells Fargo? The Bass Pro Shop?

They blend in with the background radiation of suburban housing and are eclipsed by the potency of compact development. It’s important to keep in mind that this means an acre of big box store or shopping mall is only marginally more productive than modestly sized detached housing.

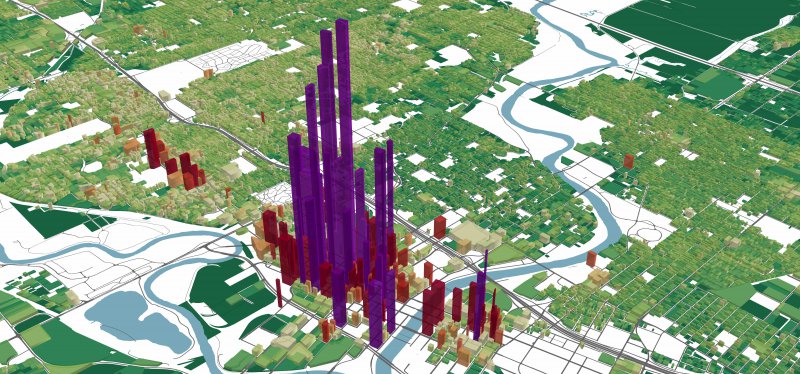

Developments such as these are not touted as success without cause. They often hold a substantial share of a community’s economic activity often producing more property tax individually than downtown buildings. What accounts for this huge disparity in efficiency though, is configuration. Parking dilutes the substantial tax production of development with fiscally barren waste. When we account for that waste we see a much different pattern of tax production.

MAPPING LAND WASTE

We can infer a great deal about the urban fabric from models like this and we can supplement that understanding with some direct concrete examples, but supplemental land cover data in this project gave us the opportunity to more directly compare efficient land use with tax productivity. This data codifies the components of development, building footprints, roads, and of particular importance, parking.

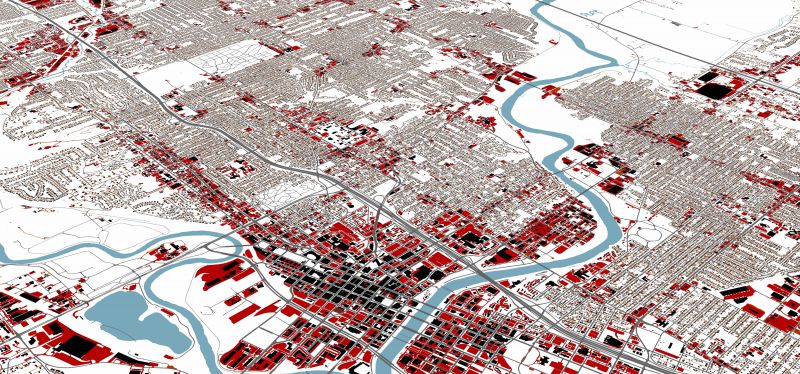

From the time of Nolli, figure ground maps such as this have been instrumental for understanding how development is woven together to form a place; what some call the urban fabric. With these other elements at our disposal we can explore a more perverse kind of map, the distribution of parking in the city shown here in glaring red. Let’s take a closer look at how different configurations of buildings and parking contribute to tax production efficiency in this example city of Des Moines.

The downtown area has the most tightly urban pattern of development and corresponds to the most potent taxable properties. Note the proportion of black to red along the four block wide swath between the rivers. This is also where the road network is the most predictable and uninterrupted. Within these blocks almost all available space is used for buildings. In short, this is the fingerprint of an urban area.

What the figure ground fails to capture is the compounded effect of not just covering land with buildings but stacking those buildings. The vast majority of development is just a few stories if that. Compact development uses all of its space and then some.

We find this same pattern again at a smaller scale even in humble Main Street settings. Notice how the configuration of the few blocks featured here have a profound impact on tax productivity. These are historic properties built before cars and car storage. The scarcity of developable land encouraged developers to maximize use of their sites. Once again using at least 100% of a lot for a building is the key to boosting tax production.

Now let’s contrast the previous patterns and height with a decidedly auto-oriented development. This is a major commercial corridor nestled along a major interchange. It boasts a shopping mall, numerous retail sites, and a substantial office park. Both configurations have considerable amounts of development and even have comparable amounts of pavement. The urban format locks small irregular developments along the street and tucks its parking off to the back in smaller pockets. The primary focus is more recognizably human. The car focused model maximizes distance between the street and the building and assembles its parking into large pools. The 3D model clearly shows financial benefits to accommodating humans on foot versus storing cars.

UBIQUITOUS PAVEMENT

One striking and troubling observation is the extent to which even the downtown is burdened with parking. The entire periphery of the potent urban core is lined with bare pavement. Downtown sits like a shining revenue oasis in a sea of flat pavement. Our small scale example too comes with its own red ring.

All the more troubling is that much of this parking was built on the remains of irreplaceable historic architecture. The proximity of these red swaths to major highway projects is also no accident. The “meat axe” of urban highway construction, as Robert Moses famously named it, tends to leave a scar in the form of broken real estate. Even within the intact urban core, parking has a conspicuous presence. This two dimensional representation also considers structured parking as though it were a building. From the standpoint of property taxation structured parking is still a structure. It is nonetheless troubling how much space is devoted to cars alone.

THE TAX CONTRIBUTION OF BARE PAVEMENT

One advantage of 3D modelling is that it gives us the ability to explore multiple layers of data at once. We typically depict both the height of the property and its color based on its tax value per acre. We can delve deeper into the question of parking by coloring property based on its relative content. In this model, height still represents value per acre. Redder properties have a greater proportion of parking, while bluer ones have more building. For our purposes we’ll ignore other uses like open space and we’ll consider driveways as though they were parking.

The result, aside from looking patriotic, is fairly noisy but nonetheless depicts a clear advantage for “very blue” over “very red” properties.

Ultimately parking is the single most important design feature that dilutes the tax productivity of development. Municipalities, for whom property taxes are their lifeblood, should treat parking for what it is: dead weight. Sadly the typical outlook found in most codes in most cities is to encourage such waste.

(All images copyright of Urban Three)

Related posts:

Joshua McCarty is Urban3’s Chief Analytics Researcher and resident Geo-Accountant. Josh’s work focuses on new ways to visualize local finance. At the core of this work is an ongoing effort to quantify, measure, and communicate patterns of urban development and the outcomes of design choices. His work focuses on the intersection of public policy, urban design, and economics. Joshua handles background work that turns raw data into relevant and recognizable patterns and is responsible for developing new analytical tools such as the 3D Tax Model. Prior to joining Urban3, Joshua worked as a researcher quantifying sprawl and environmental impacts in the Chesapeake Watershed and nationally. His graduate education at the University of North Carolina’s Department of City and Regional Planning focused on real estate development.