The Emerging Democratized Economy

Today we welcome a new Strong Towns writer and member, Alexander Dukes. Alexander stood out to us for his intelligent and thoughtful comments on our website over the past year. This essay will be the first in a series on "The Democratized Economy." Read the second article: "The Democratized Economy: Big Boxes, Urban Centers and Placemaking' or the third article: "The Democratized Economy: How to Build a Successful Urban Center."

A coal miner in Appalachia, 1946. Photo by Russell Lee

We’ve all heard of small towns whose economies have been devastated by the depression of a national industry that employs most of the townspeople. Appalachian coal mining towns are becoming the latest victim of this phenomenon due to the decreasing cost of renewable energy. These towns’ reliance on only a couple of employers to sustain their economy sets them up to be communities with a single point of failure. When these towns’ economies are only subjected to the economic stresses they were designed to handle, they perform quite well. On the other hand, economies with a single point of failure tend to break when they encounter an unexpected economic condition- like falling renewable energy prices.

Our communities’ tenuous relationship with these massive employers is not some recent accident. Rather, this state of reliance is built into the economic culture we’ve harbored in the United States since the beginning of the 20th century.

The Modernist Economy

Our current national economy looks to a relatively small cadre of massive corporations to drive economic growth. This economy came of age during the industrial revolution. A product of its time, it is deeply associated with the early 20th century dogma of “the one best way” and “form follows function.” For this reason, I call it “the Modernist Economy.” The Modernist Economy is defined by large national and multinational corporations that use mechanization and standardization to achieve mass production.

Prior to the advent of mass production, most communities relied on highly skilled craftsmen to produce goods for their regional market. Each product produced by the craftsman tended to be fairly unique to the individual and was adapted to the region from which the maker hailed. The market for most consumer products at this time was the same region in which they were produced.

When the Modernist Economy arrived, comparatively less-skilled laborers were employed on a massive scale to produce goods and services with the aid of machines. The volume of products produced by the modernist corporations greatly outpaced the craftsmen. Further, modernist corporations took advantage of new transportation options like railroads, canals, and highways to expand product markets from the regional scale to the national and multinational scales. Unable to compete with the modernist corporations on volume, market penetration, or price, the majority of American craftsmen were driven out of business.

“Because there are only a few companies left in many industries, communities feel they have nowhere to turn except to these massive corporations to drive local economic growth. ”

The phenomenon of larger companies forcing smaller firms out of business has continued among the Modernist firms themselves. Over time, the capital requirements needed to sustain mechanization and mass production have priced all but a few companies out of their respective industries. Through mergers and market share dominance, the practice of pricing out the competition has only allowed the surviving companies to grow larger.

This is why so many of our communities are totally reliant on one or two industries to sustain their economies. Because there are only a few companies left in many industries, communities feel they have nowhere to turn except to these massive corporations to drive local economic growth. Communities that lack local industries sufficient to sustain their economies are often desperate to attract companies. The odd phenomenon of giving away huge tax breaks or massive infrastructure gifts to attract far away employers is the logical result of this local industry shortage.

Fortunately, it seems that a grassroots reaction to the modernist economic ethos of standardization and mass production is beginning to birth a new economic paradigm.

The Democratized Economy

Demos, the root word for democracy translates from Greek to English as “the common people.” A “Democratized Economy” is an economy that looks to the talent and wisdom of the population at large to drive the economy. Unlike the Modernist Economy, the Democratized Economy does not see the public merely as “consumers-” to whom a few industrial titans sell products. Rather, the Democratized Economy views the public as a resource from which new ideas and products emerge spontaneously. The Democratized Economy is defined by a more inclusive culture of production that pulls us back to regional economies based on locally crafted products that are specialized to serve niches that the Modernist Economy ignores.

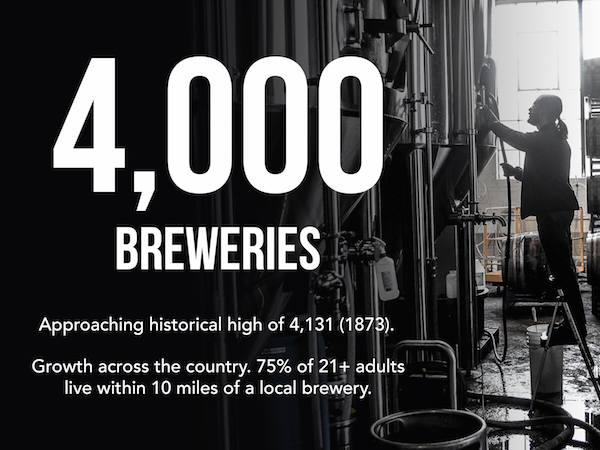

The recent popularization of craft beer across the United States is just the latest example of specialization becoming the norm. Craft beer companies have no need for Anheuser-Busch’s automated assembly lines and massive labor force. Rather, craft beer companies rely on a few local craftsmen that manage every step of the beer-making process. This combination of skill and a lean labor force gives craft beer companies a distinct advantage over Anheuser-Busch: the ability to adapt their product to a regional market.

Without having to commit thousands of workers and machines to a new product, craft breweries can quickly and easily adapt to their respective region. Of course, craft brewers will never make as much revenue as Big Busch, but being big isn’t the point. The point is to be sustainable at an appropriate scale. For craft breweries, the “appropriate scale” is to be a locally owned and operated seller to a regional market.

It is important to note that local craft breweries still have ample room to grow. The U.S. population has grown a bit since the brewery climax in 1873. To reach a brewery per-capita equivalent to 1873, there would have to be 30,000 breweries in the United States today. No one expects the number to reach that height anytime soon; however, it does give you an idea of the hyper-locality of the pre-Modernist economy, and how much more local we can become. (Source)

These craft brewers are seeing success at their smaller scale. In 2015, the Brewers Association calculated that there were more than 4,000 breweries actively making beer in the United States. This is the highest number of brewers since 1873, when there were 4,131 breweries. For perspective, in 1970 there were fewer than 100 breweries nationwide. By the mid 1990’s craft breweries began a gradual resurgence that as steadily grown to the current fever pitch of about a thousand new breweries opening every year.

The Democratized Economy’s leaner, more specialized means of producing goods and services is not just limited to beer companies. The advent of digital distribution has allowed highly specialized music production facilities to take root in many small cities across America. The progressive internet news network, “The Young Turks” is an example of a smaller, more specialized media company that could (and sometimes does, using local correspondents) broadcast from any town with an Internet connection. Online seller Etsy’s whole existence is based on linking leaner, more specialized producers with customers. And as 3D printing continues to improve, many believe that the 21st century equivalent of a blacksmith’s shop will emerge to produce local consumer products on demand.

New localized ventures like craft breweries, micro-music studios, small-scale news networks, and local consumer product manufacturers are the “canaries in the coal mine” for the democratized economic paradigm. Towns and cities should leverage the accessibility of the Democratized Economy to move away from their dependency on one or two massive employers in a national industry. Instead, local economies should be based on several smaller employers in a variety of industries that serve their respective region. In practice, this means communities should focus less on begging non-local corporations to bring jobs to their town, and focus more on supporting their own local entrepreneurs to build their economy from the bottom up.

Ultimately, the key to building a sustainable local economy is to nurture a diverse set of employers that operate in multiple industries. In the Modernist Economy, only larger cities could hope to achieve this due to corporate consolidation. With the emergence of the Democratized Economy, localized production for regional markets is returning to the fore. It will eventually allow smaller communities to achieve economic diversity by playing host to their own home-grown, regional scale ventures. Our communities should seize this opportunity by investing in their local population to encourage the spontaneous entrepreneurship at the heart of American culture, and the Democratized Economy.

(Top photo by Khara Woods)

Related stories

About the author

Alexander Dukes is a United States Air Force Community Planner working at Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst in New Jersey. He is a graduate of Tuskegee University and Auburn University, with a Bachelor’s Political Science and a Master’s in Community Planning, respectively. With this background, Alexander focuses his planning work on both urban public policy and the design of the physical realm for both military and civilian applications. Alexander is principally concerned with building sustainable cities, towns, and neiborhoods that provide all citizens- regardless of income or ethnicity, with access to meaningful employment, civic resources, and beautiful places.