Is this new high school really an upgrade?

Matt Steele is a founding member of Strong Towns and writer for the Minnesota land use and transportation blog, Streets.MN. This essay is reprinted from Streets.MN with permission.

A couple years ago, Alexandria, MN built a brand new high school. It was immediately highlighted as a model of innovation by many, including in this piece by Jenna Ross in the Star Tribune:

This $73.2 million high school, recently heralded “the Googleplex of Schools” by technology magazine Fast Company, reflects a broader shift in education and is already becoming a template. Students have given more than 50 tours of the place — 40 of them to officials and teachers from other school districts. Looking to build one high school and renovate another, St. Cloud folks stopped by, then hired the same architects.

The new facility, designed by Cunningham Group in Minneapolis, may be a model 21st Century education facility. An investment in the education and future of a city should be applauded, and I’m glad to see we are constantly re-evaluating the environment in which students learn the best.

Yet this is part of a depressing trend in modern school planning, playing out in other Minnesota towns like Mankato, New Ulm, and St. Cloud: isolated schools on the unwalkable fringe. This one appears no different. Fast Company notes, “When the city of Alexandria, Minnesota, asked community members what they wanted in their new high school to be like, they replied, ‘like the Google campus.'” Fitting, since Google operates hundreds of buses each day to shuttle workers from their walkable San Francisco neighborhoods 40 miles south to their sprawling Mountain View campus.

Location matters

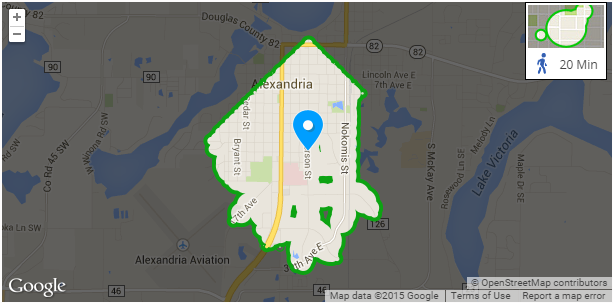

The old high school in Alexandria is located at 1401 Jefferson, on the southern fringe of Alexandria’s traditional development pattern and humane grid. It had a Walk Score of 42. A majority of the traditional grid was within a 20 minute walkshed, and even the northern fringes of the city were within 20 minutes by bicycle.

Looking for a safe route? Take your pick on the grid!

The new high school a mile and a half south, surrounded by farm fields and an active railroad track. It has a Walk Score of 8. There’s literally no pedestrian shed to show. Even if students wanted to bicycle on the shoulders of unsafe high-speed rural highways, they couldn’t get to town within 20 minutes.

Want a safe route to school? Nope. And this bikeshed is giving you the finger for asking.

Not even a Safe Routes to School grant will fix this land use mistake. The school district will need to pay to bus students, who used to be able to walk or bike, in perpetuity. Students will be more likely to drive, and no longer have active lifestyle choices for their school commute which will likely cascade through their adult lives. Students who cannot afford a car or aren’t capable of driving will be even more isolated and less likely to participate in enriching after-school sports or activities that do not coincide with a busing schedule.

A lesson for other school districts

In the Star Tribune piece, classrooms are equated to “cell-like boxes.” Other references are made to classrooms as the “c-word.” Okay, we have a prison metaphor. A prison isolates. So does two miles of farm fields. The promotional video (below) from the architect, who usually builds quality work in human-scale environments, starts with a hubris-laden quote from (anti-urban?) Buckminster Fuller: “The best way to predict the future is to design it.” If that’s the case, let’s design our schools to integrate with the built environment of the community they serve, rather than isolate from it.

Alexandria’s new school is already built, and the old one, demolished. So let’s not dwell on their case study. But let it be a lesson for other school districts who can choose to build their new school facilities in a land use that connects students with their communities.

We need build beautiful, enriching school facilities. But let’s build them in beautiful, connected places.

In the battle for street safety, crossing guards are on the front lines. Their verdict: The streets outside of schools are extremely unsafe. One crossing guard in Denver decided to do something about it.