Revisiting: Distorted Housing Prices

In October 2016, we ran a series of articles from Charles Marohn about Portland's housing challenges—inspired by a Strong Towns trip to Portland. This week, in light of a new series we're running about incremental development, we felt it was time to revisit this Portland housing series and continue this important discussion about affordable housing, incremental growth and what it all means for modern American cities. If you'd like to skip ahead and read the whole series, you can do that here, but if you'd like to join the conversation this week (and we hope you do) please read on and comment with your thoughts. - The Strong Towns Team

Recently, I wrote about all the ways people explain the very high housing prices in a place like Portland, Oregon and why I found those explanations lacking. To summarize, while Portland is nice, it's not so extraordinarily nice as to defy natural market mechanisms. Portland could build more housing, but there's no evidence that housing is not keeping up with demand at current prices. Yes, Portland is cheaper than San Francisco, but so are a lot of places that are not experiencing such huge distortions. And there is decades -- perhaps centuries -- worth of developable property within the current urban growth boundary; the UGB is not creating an artificial scarcity.

So what is going on?

There are two parts to this conversation. One is psychological and one is financial. I've chosen to deal with the financial today and will tie in the essential psychological element in a follow up. To explain the financial, I'm going to present a hypothetical situation that I've seen in Portland as well as other bizarre housing markets like Austin, Texas and Northern California.

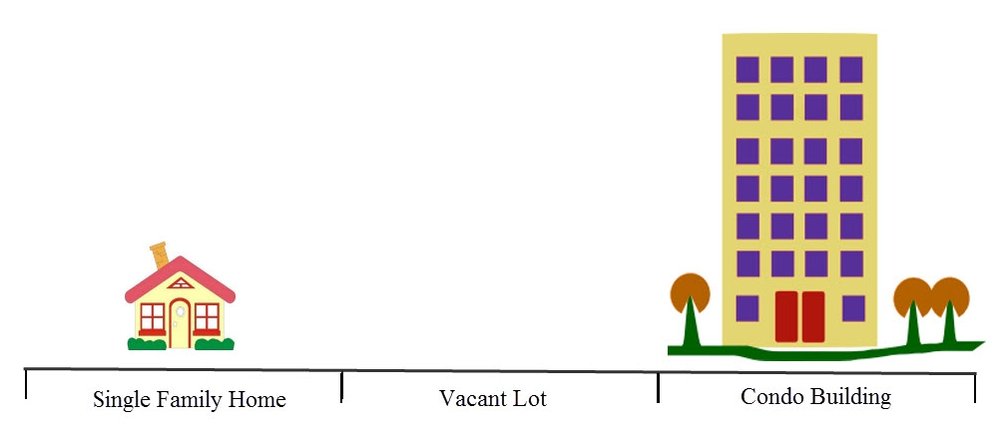

Consider three adjacent parcels of identical size, shape and all other defining characteristics. One contains a single family home that was built prior to the construction of Portland's light rail line. The second is a vacant lot. The third parcel contains a condominium unit that was built along the rail corridor consistent with the theory of transit oriented development (TOD), the idea of promoting increased density in areas where significant transportation investments have been made (i.e. "build it and they will come").

Let's consider a situation where the vacant lot in the middle is put up for sale. What should the asking price be? The most logical way to make that determination is to look at the adjacent properties and determine how the parcel could be developed. What is its highest and best use?

We see that the single family home is valued at $200,000 while the condo building is valued at $10 million. If you owned the vacant lot, how much would you ask for it?

You could look to the left and see a single family home and deduce that, if the purchaser of the parcel was going to build a single family home consistent with the local market, they could pay up to $30,000 for your parcel and still make the math work. However, if you look to the right, you'll realize that someone buying the parcel with the intention of building a condo unit could pay 50x that much, about $1.5 million.

Would you rather have $30,000 or $1.5 million?

Of course, the sale price of the parcel is going to reflect the highest reasonable possible use. With the TOD regulations in place encouraging the maximum use of that rail investment, that means the vacant parcel is going to sell for $1.5 million, a nice haul for the lucky individual who wound up with land near the rail line (I'm assuming there was no assessment when the rail line was built) and sold before the real estate bubble burst (more on that later).

Let's turn our attention to that single family home. It now sits next to a vacant lot worth $1.5 million and a condo unit worth $10 million. How much is that single family home worth?

Whatever the answer is, we can clearly see that it's not worth $200,000 anymore. With the vacant lot going for $1.5 million, all of the value of the single family home is now in the land. The home itself is essentially worthless, a scrape-off building that actually lowers the value of the property due to the demolition costs. The single family home in this situation is worth nearly the same as the vacant lot, $1.5 million.

In my next article, I'm going to explain how these elevated values get transmitted outside of the TOD areas, but before I finish today, I want to point out how this financial mechanism explains two unique features in cities where this is happening.

I mentioned in my last piece that I was shocked by how nice the nice parts of Portland were and how bad the bad parts of Portland were. There wasn't a lot in between, at least not that I saw. I believe that is because the development approach I've explained today represents an all-or-nothing, binary kind of endeavor. If you owned that single family home, would you install granite counter tops? Would you put in a Jacuzzi tub? Would you spend money on landscaping the back yard? Of course not. You own a home that's worth over a million dollars, yet it has none of the things a million dollar home would have and the reason is simple: you would never get that money back. The house is going to get torn down whether it has granite counter tops or not. Adding them may marginally improve your life, but it doesn't change the value and thus is a bad investment. The same goes for mowing the yard or picking up the trash, I'll note.

“The land values are so high, and the building values comparatively so low, that it actually makes financial sense for the very affluent to buy the parcel, tear down the building and build their own multi-million dollar home.”

You see this artificial distortion creating all kinds of unnatural side effects, such as the McMansion scrape off. The land values are so high, and the building values comparatively so low, that it actually makes financial sense for the very affluent to buy the parcel, tear down the building and build their own multi-million dollar home. That kind of thing may seem normal to those that have grown accustomed to it, but historically it's an aberration.

One last thing to note: If every parcel in Portland (or Austin or Northern California) that had unnaturally elevated land values were to be redeveloped to its highest and best use—the use that would justify those property values—then Portland would need millions more people. Perhaps tens of millions. That will not happen in any kind of reasonable timeframe so what is going to happen -- what must happen -- is that, at some point, supply will exceed demand and prices will fall dramatically. Everyone who sold before the inflection will be huge winners (condo-inflated prices). Everyone who sells after will get normal single-family home prices.

It's just like a stock market bubble with all the animal spirits and irrational exuberance, except for the fact that housing prices, like wages (but unlike stocks) are sticky. More on that in a later article.

And by the way, if you're new to Strong Towns, don't start thinking that I'm anti-transit just because I'm questioning the impacts of a rail station in this neighborhood. I'm very much not against transit. What I'm against though, is the build-it-and-they-will-come gambling and the market-distorting theories that go along with it. I also find immoral a system of local government finance that benefits -- by creating financial bubbles -- today's office holders and bureaucrats at the expense of tomorrow's America.

(All graphics created by Charles Marohn)

Charles Marohn (known as “Chuck” to friends and colleagues) is the founder and president of Strong Towns and the bestselling author of “Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis.” With decades of experience as a land use planner and civil engineer, Marohn is on a mission to help cities and towns become stronger and more prosperous. He spreads the Strong Towns message through in-person presentations, the Strong Towns Podcast, and his books and articles. In recognition of his efforts and impact, Planetizen named him one of the 15 Most Influential Urbanists of all time in 2017 and 2023.