The Clemens House Paradox: When Development Dollars Speed Neighborhood Decline

The Northside of St. Louis, Missouri, is disappearing. That isn’t a figurative statement, nor is it simply waxing lyrical about the slow tragedy of urban decline. It’s literal: whole houses are being stolen, brick by brick, off of their foundations, by thieves who leave only stone facades and heaps of destroyed millwork behind. Buildings that, in virtually any other city—or even in another neighborhood of St. Louis itself—would be considered historic treasures to be carefully guarded by preservationists and fussed over by groundskeepers are being targeted by arsonists and vandals instead.

One of the most recent buildings to vanish is the James L. Clemens House, formerly one of the city’s most intact antebellum mansions and home to a relative of Mark Twain (yes, we’re talking about that Clemens family). In the early hours of the morning, flames engulfed the property, possibly ending decades of hope for the restoration of a city landmark in a single blaze. While no cause of this fire has yet been identified in local media, what we do know about how the Clemens House burned shines a light on some of the greatest challenges facing Northside St. Louis, and the uncomfortable realities of how we seek to revitalize so many of our cities and towns.

To understand the Clemens House tragedy, you first have to understand the landscape of north St. Louis. A combination of white flight, disproportionate government subsidies for central corridor development at the expense of Northside neighborhoods and other forms of systemic disinvestment (more on that later) has left the region deeply segregated, cash-strapped and crumbling. In all but a small handful of neighborhoods north of the city dividing line at Delmar Avenue, between 90 and 100% of residents are black, and median household incomes hover around $18,000 per year in the neighborhoods closest to the divide. Unsurprisingly, this stratification isn’t good news for the housing stock: median home value in that particular neighborhood is stuck at $73,000 (compared to $335,000 south of Delmar) and the majority of St. Louis’ 12,000-some tax delinquent and abandoned properties, many in dangerous disrepair, are located there.

The Clemens house, though, wasn’t tax delinquent, nor was it abandoned. It was dilapidated before the fire, but it did have an owner, and that owner had spoken publicly for years about his plans to restore this local landmark to its former glory.

The only problem? That restoration never materialized. And that same developer has been promising the restoration of literally hundreds of crumbling buildings on the Northside for over a decade.

The owner of the Clemens house is Paul McKee of Northside Regeneration, LLC. McKee is a Northside native and professional developer who’s become controversial for, some would say, not doing much development at all, and doing so for carefully guarded reasons that raise significant questions about how we revitalize our town’s most disinvested neighborhoods. Local architect, preservationist and writer Paul Hohmann recently gave an excellent summary of McKee’s contentious history in the region for his excellent Vanishing STL blog; I recommend that you read it in full, but here’s a thorough excerpt:

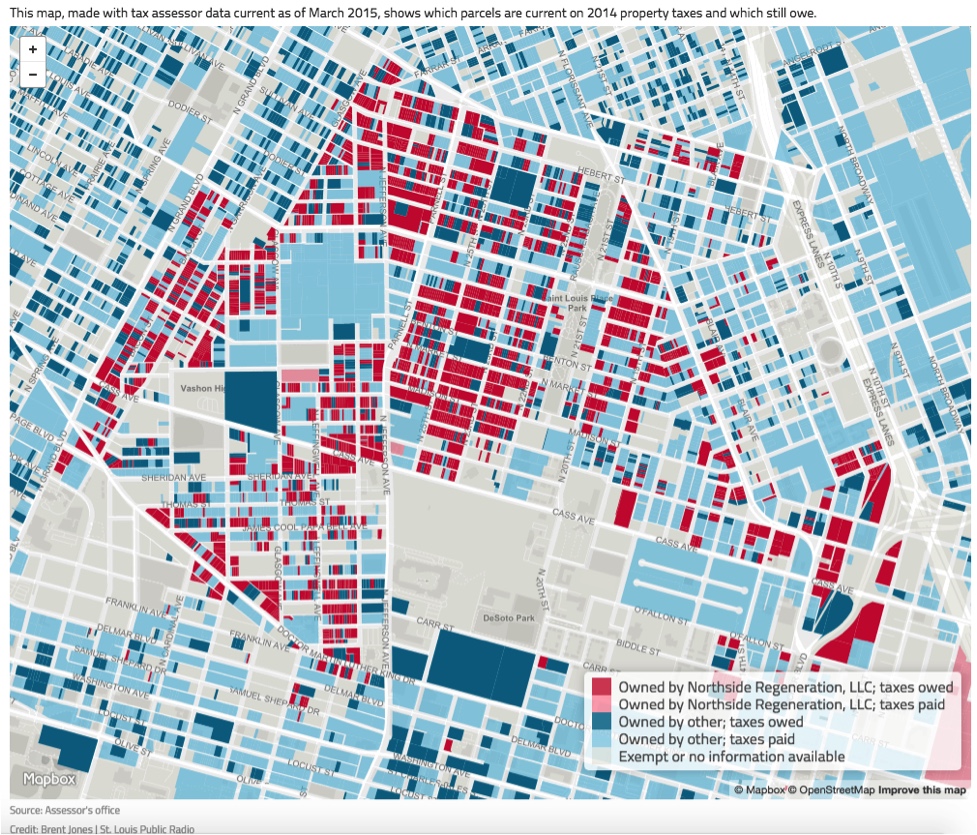

After spending years secretly acquiring thousands of buildings and vacant parcels through anonymous shell corporations, Paul McKee publicly revealed his grand plan for Northside in May 2009. The plan he said would include 3 million square feet of office and retail space, 1 million square feet of light industrial space, hundreds of new apartments and single family homes, parks, street improvements and even its own trolley system. In October 2013 the St. Louis Board of Aldermen approved $390 Million in TIF [or tax increment financing] for McKee's Northside plan. Additionally, the State of Missouri gave McKee $43 Million in Distressed Areas Land Assemblage Tax Credits. The Land Assemblage Tax Credit was custom written by McKee's lawyers and due to the large quantity of land required to be purchased, he is to date the only recipient.

Since unveiling the grand plan for "Northside Regeneration" over eight years ago and with hundreds of properties now owned for over a decade, McKee’s track record as a property owner has been nothing short of abysmal. The reality has been [what might seem like] an intentional Northside Disintegration. Buildings owned by Mckee, many of which were occupied and in decent condition, were immediately emptied and left unsecured. Doors and windows mysteriously disappeared hastening the cycle of intentional demolition by neglect. Many buildings succumbed to demolition by brick theft, and many of these were were hastened by arson fires. See Built St. Louis' pages on Blairmont, one of several of Mckee's shell companies that purchased the properties. Note: Almost all the beautiful historic structures on the page linked above have since been demolished.

While there are certainly many other absentee landlords who abandoned their properties and let them rot and crumble (St. Louis Public Schools could be included on this list), the sheer quantity of historic buildings that have fallen in the last 10 years as a direct result of McKee's blatant and [some would say] intentional neglect has probably not been seen since the days of urban renewal clearance in the 1960s. It only seems less dramatic because it has occurred over a decade...Out of all that was to come from the grand plan, the only Northside project McKee has completed is a moderate rehab flip of an existing office warehouse building.

It’s relatively clear how McKee came to be the owner of hundreds of derelict properties, and even how he was allowed to maintain ownership of them as they declined; it’s important to note that fines for building code violations are on the negligible order of $25 per violation, as are court costs for developers cited for chronic non-compliance, which the building department told me run “about $200”, both of which are low costs of doing business.

But until recently, it’s been less clear to St. Louis residents why anyone would choose to buy so many acres of crumbling brick simply to let it rot. One explanation, as local preservationist Michael Allen has postulated, is that all those cheap, unusable buildings can become shockingly valuable when the developer has amassed enough acreage for a land bank, especially if development in the rich central corridor ever expands beyond that stark Delmar border.

And some think McKee’s moment to cash in has already arrived; recently, the city bought back land it had previously sold to McKee in order to establish a campus for the National Geospatial Institute, a move that the city hopes will create jobs. (Ironically, this area is the site of the former Pruitt-Igoe housing complex, one of the most significant cautionary tales in urbanism about the hazards of large-scale transformative development.)

McKee initially paid an estimated $3-6 million for the property, inclusive of legal fees; the city bought it back later for $12 million. And while every dime of that money went to pay McKee’s debts, he still owns such a significant land mass that it’s not hard to imagine that opportunity might knock again soon. City voters recently rejected a proposal to fund the purchase of land from McKee to build a professional soccer stadium; some think it’s only a matter of time before McKee will get another shot at a payday.

And while he waits, his history suggests that the buildings he owns may continue to crumble and burn.

So often, our debates about city economics run up against hard binaries. Pro-development vs. anti-development. Reinvestment and revitalization vs. disinvestment and dereliction. Yet McKee represents a breed of developer who falls somewhere in the middle: someone who’s invested heavily in a region on paper, but who, for whatever reason you choose to believe, has undoubtedly contributed to his region’s drastic decline. The city of St. Louis can claim no small part of the blame here; they’ve chosen to heavily subsidize McKee’s efforts through tax increment financing packages—the largest in city history—and they’ve chosen to encourage a real estate market that, for better or worse, permits a single developer to buy up parcels totaling more than 1,500 acres, many of them in strategic areas where the central corridor is highly likely to expand.

When those tax deferment packages expired, by the way, McKee didn’t always pay.

But we’re all to blame for this, a bit—and more importantly, we’re all equipped to change it. As a society, we’ve created, sustained, or chosen to ignore a culture of development that favors silver-bullet transformative projects, whether they come in the form of a single massive development like a soccer stadium or a single massive developer who buys up a significant fraction of a vulnerable area and promises (whether he actually intends to comes through or not) to remake it all. We’ve ignored the centuries of evidence that this, simply, is not how towns have ever grown strong.

Look at the above graphic above again, and imagine for a moment that every red and pink parcel on it was owned by someone who cared. Imagine a city that had invested in low-cost, small-bet projects: putting eager homeowners in those beautiful old greek revival style brick houses and equipping them to shore up the foundation and patch up the roof, experimenting with narrowing the wide stroads that connect those gorgeous, pre-auto-centric neighborhoods.

Picture the real people who’d be a part of this change: individuals with real skin in the game, for whom property wasn’t just an abstract real estate investment, but a home and a hearth, for themselves or their tenants. Imagine if we had city governments that paused a bit longer before a big developer asked to buy a property and skip the tax for a few years; imagine if our leaders had a better way of looking past the seeming short term win of getting some money back into a disinvested neighborhood and asked a different set of questions about the long term implications of the bet they were making. Imagine if properties like the Clemens house, even post-fire, were owned by someone who took steps to secure it and, eventually, make it shine; Hohmann is sure that it isn’t too late.

We can have that, in St. Louis and beyond. But we all need to demand it.

(All images courtesy of Vanishing STL unless otherwise noted.)