What one town's history shows us about economic reliance on a single industry

The Peoria waterfront in 1909

In many ways, Peoria, IL is a typical Midwestern town. It’s full of parking lots and big box stores, and marked by poverty, but it also has beautiful buildings, passionate residents and an intriguing history which gives us clues to its present day predicament. If we pay attention to that history, we can learn something about the mistakes we're still making today and have the chance to right our course.

Peoria's Past

In the early 1900s, Peoria was known for one big industry: It produced close to one fifth of the nation’s liquor. At their height (in 1917), the distilleries in Peoria rolled out more than 62 million gallons of alcohol.

In an article for the Peoria Journal Star covering the history of the region, Brian Ellis, a local historian, remarks:

"Peoria provided the perfect alignment of everything you needed for the production of alcoholic beverages: good spring water filtered by limestone, a river that provided transportation, a rail hub and lots of corn. [...] You also had the experience of two of the biggest groups to settle this area: Germans and Irish. Both knew how to distill, and both were thirsty."

Liquor production in Peoria began in 1837 (a few years before the area was even incorporated as a city). By 1860, the town was home to nine distilleries and six breweries, and business only grew from there. The map below gives an approximate idea of the “Distillery Row” area (the white box) which took up much of downtown Peoria’s waterfront.

Keep this image in mind because it will be important later. (Source: Google Maps)

Not only did liquor production create profit for the city and jobs for its residents, but it also inspired a number of related industries, which contributed to the economy, too.

An article in Peoria Magazine explains:

Many of the houses along Peoria’s High Street and Moss Avenue owe their existence in one way or another to whiskey, for distilling spawned a host of related businesses. It required woodcutters, sawmills and barrel makers. The resulting sawdust was used by ice houses in the summer. Since one of the byproducts of whiskey was wet mash or slop, which made an excellent food for cattle, huge herds were maintained in an area near the foot of Western Avenue. As many as 28,000 animals munched contentedly on this alcoholic mash.

The presence of all these cattle made Peoria a major center for the dairy industry and for meat-packing houses. Other offshoot occupations included delivery wagons, repairmen, veterinarians, blacksmiths, farriers, shippers, drovers, stockyard workers, label printers and even workers whose specialty was caulking leaking whisky barrels with papyrus….

But, like all booms, this one couldn’t last forever. In 1919, the 18th Amendment passed and one year later, Prohibition began. This spelled the end of jobs and economic output for the sprawling liquor industry in Peoria. The 18th Amendment was repealed in 1933, but 13 years of no business was enough to kill the industry. Something that had once defined Peoria disappeared, never to return to its former glory.

Today, it’s hard to imagine a federal legal decision resulting in the elimination of a huge economic driver without some sort of bailout to ease the pain. Even with a subsidy though, it's unlikely the liquor business would have survived, especially given that the Great Depression started soon after Prohibition. For Peoria, there was truly no lifeline.

Peoria's Present

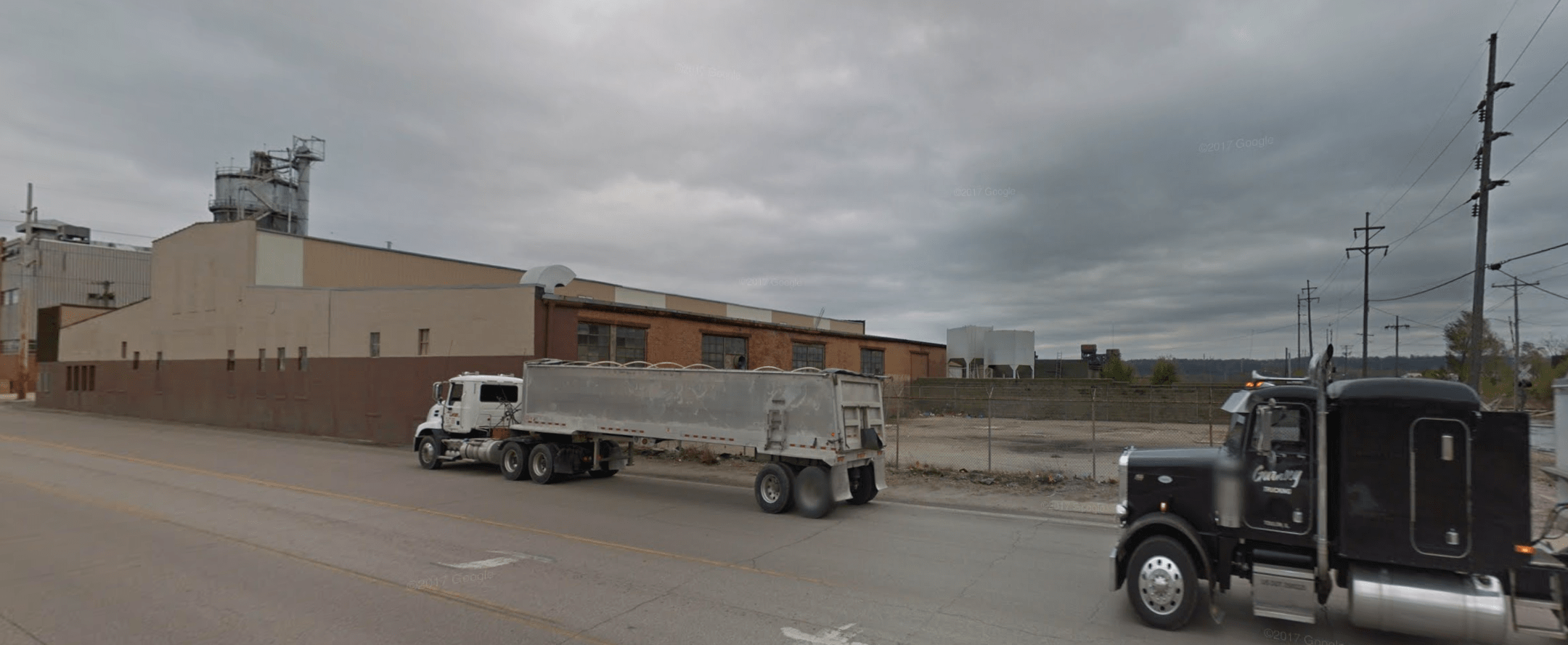

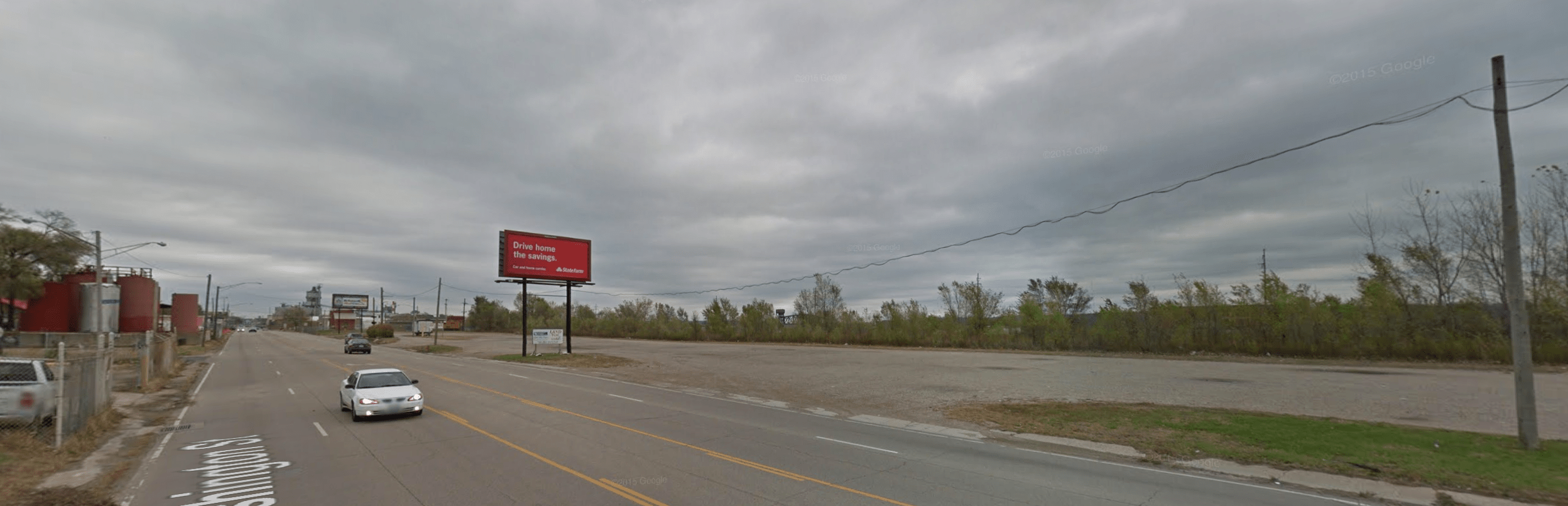

What became of this city in the aftermath? Its warehouses, factories and other buildings involved in the liquor business emptied out and were later replaced with parking lots, some small industrial businesses and the occasional restaurant. That white rectangle of land has become this:

(Images from Google Maps)

Empty and ill-used space.

Peoria wasn’t completely destitute though, because just before Prohibition, another industry had appeared on the scene.

[Caterpillar] started somewhat inauspiciously in 1910 at a time when Peoria had a wealth of prosperous industries, cranking out everything from plows and bicycles to automobiles, tractors and washing machines. Then, the Holt Caterpillar Co. operated out of a small East Peoria plant that employed 65 people by year end.

At a time when Horace Greeley was urging Americans to go west, the California-based Holt Manufacturing Company decided to add a plant in the east. […] The company began its major growth during World War I, as the Holt Caterpillar track-type tractor proved adept at dragging heavy artillery equipment through the mud of the Western front. Thousands of these tractors were sold to the Allies.

The enormous Caterpillar Administration Building in downtown Peoria (Source: Roger Wollstadt)

The company weathered the Great Depression and then “received a major boost from the outbreak of World War II.”

Today, Caterpillar facilities dominate both downtown Peoria and East Peoria (the sister city across the Illinois River). Caterpillar employs more people than any other business in the area and the company is mentioned many times in the city’s budget plans. It's a huge player in Peoria.

But Caterpillar was not the knight in shining army that Peoria might have hoped for. Earlier this year, the company announced it would be moving its headquarters to Deerfield, IL, once again leaving Peoria in the dust.

Over the last several decades, with an awareness of this history, the city has worked to shift its reliance on one industry and has expanded to include other major employers in the healthcare, banking and technology industries. Efforts to support smaller businesses through groups like Start Up Greater Peoria are also helping to change the economic landscape of the region. Still the process to build an economy that isn't reliant on one or two industries is an ongoing challenge that won't be accomplished overnight.

---

The story of Peoria is not so different from many other towns’ stories. A community builds itself up around one primary industry—be it healthcare, technology or tourism—and when that industry disappears, they’re left to pick up the pieces. Just like Peoria, we haven’t learned our lesson from the stories of the past. We pull out all the stops to attract a Walmart or a new tech company, only to see the business close up shop and leave a few decades later.

This is a cautionary tale, but it doesn't have to have a sad ending. We can start paying attention to our history and learning from this lesson. We can't put all our eggs in one basket and delude ourselves into believing it will last forever.

We need to encourage local food systems, develop import replacement strategies and shore up diversified local economies, full of small businesses and not reliant on one big industry. Only then will we have strong towns.

A big thanks to Josh McCarty and the team at Urban3 for their research into Peoria.

(Top image source: Google Maps and Urban3)

We talk with author Jake Berman about the history of rail networks in America’s cities and why our transit systems are the way that they are in the current era.