The Good Samaritan in the Age of the Automobile

This morning’s guest post breaks a bit from the usual Strong Towns mold. Our good friend Vince Graham wrote to us to share this personal story of an encounter he had on an Atlanta sidewalk in April, along with some meditations on the very real human stakes of the way we build our places—which can either serve to connect us, or to drive us apart. We’re pleased to share it with you.

My Encounter With Stanley Melvin

In the Parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25-37), Jesus responds to a lawyer’s question: “Who is my neighbor?” by telling a story of three men traveling along a narrow road between Jerusalem and Jericho. Each of the men is separately presented the same opportunity: choose to extend compassion (be a neighbor) to a beaten man, left for dead on the side of the road; or keep walking down to Jericho. Upon approaching the beaten man, the first two, a priest and a Levite, choose to “pass by on the other side,” going out of their way to avoid an encounter. The third, a Samaritan, chooses to help.

A conclusion one can draw from this story is that when given the opportunity, one out of every three people who encounter a person lying helplessly on the side of a road will choose to stop and help.

The story also provides the reader a choice: regret that only the Samaritan stopped to help; or be grateful he was willing to do so. And what about the road Jesus chose as the setting for the story? What role did that play?

I have a theory: Modern thoroughfares advance a dehumanizing tendency. Given the isolating circumstance created by contemporary streets, most of which are designed for motorists sealed up in metal boxes moving at relatively high speed, the proportion of passers-by willing to extend compassion to a helpless person lying alongside a road falls to less than the one third in Jesus’s parable.

My mother was admitted to Northside Hospital in the early spring of 2018. While there, my family received the terrible news that she had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Shortly thereafter we were able to take her home where she could be more comfortable. On April 6, 2018, my father and I took her back to the hospital for a procedure that involved draining fluid that had accumulated in her abdomen. What was supposed to take 30-45 minutes ended up taking several hours. While waiting, I went to lunch, then took a walk.

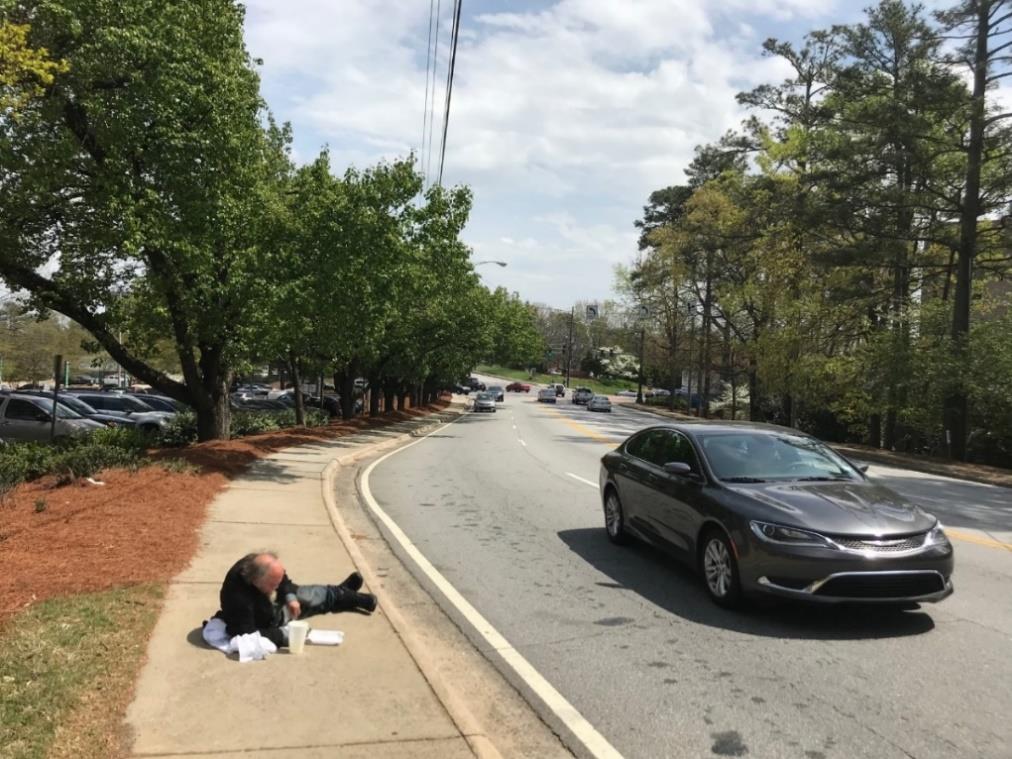

Just down from the corner of Johnson Ferry and Peachtree Dunwoody Road, I saw a man lying on the sidewalk. Seeing an opportunity to test my theory, I pulled out my iPhone to take a few photos and videos of passing traffic, and see if drivers would stop, or even pause to check on the man. Regrettably, no one even paused or rolled down a window.

I approached the man and asked if he was ok. In a strong voice, he said, “Yes, just hungry.” I offered to buy him lunch. He stood and readily accepted. We shook hands and introduced ourselves. His name was Stanley Melvin. Articulate and friendly, he looked to be in his mid-70s. In conversation during our walk to the hospital cafeteria, I learned we shared things in common. Stanley was born at Emory Hospital (as I was), grew up in Atlanta (as I did), enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps after high school graduation, and completed basic training at Parris Island, SC near Beaufort (where I used to live). He later served two tours of duty in Vietnam. During his second tour, Stanley was shot several times including in the forehead, the scars from which he still bore.

Hospital security guards gave us a look as we entered the building, and in a low, gravelly voice Stanley mentioned they had previously given him trouble. I thought nothing of it and we proceeded to the cafeteria. Next door to the cafeteria is a McDonald’s restaurant. Standing in line at McDonald’s was a man wearing a “Vietnam Vet” baseball cap. Stanley stopped to say hello to the man and engage in brief conversation: “When were you in ‘Nam? What unit?, etc.”

Proceeding to the cafeteria line, Stanley selected pasta, broccoli, hush puppies, and lemonade. After paying, we found a table. Continuing our conversation, Stanley told me that after recovering from his wartime injuries, he left the Marine Corps, returned to Georgia, and got married. He was married for 25 years until his wife died of cancer. He now lived on the street, sleeping in MARTA train stations. I asked about a military pension. Waving off that idea, Stanley informed me a pension required having an address, and a post office box cost $25/month.

Two uniformed hospital security guards—a man and a woman—approached our table and asked what was going on. Puzzled, I said, “We’re having lunch.” They informed me Stanley had previously been arrested for trespass and wasn’t allowed in the hospital. I protested saying we had just sat down. One guard sympathized, but said Stanley had to go.

Stanley started to back talk, accusing the guards of not respecting their elders or veterans. As it was a lovely spring day, I suggested we leave and eat outside. The guards followed us out, with Stanley continuing to give them a piece of his mind.

We went out to the sidewalk along Johnson Ferry Road at the hospital’s entrance where Stanley plopped down and continued eating. Feeling the need to go back and check on my mother, we said our goodbyes, and I left him picnicking on the sidewalk.

Back in the waiting room, my father came out to report that Mom’s procedure was complete and they would soon bring her out.

Exiting the building to retrieve the car, I saw two police cars and an ambulance along the sidewalk where Stanley had been. My first thought was “Oh no, Stanley got hit by a passing car!”

Running over, I asked one of the three policemen on the scene what happened. He said, “Oh, just some drunk guy trespassing. He’s in the ambulance. Standard procedure.” I asked to talk with him, and the surprised officer said “Sure, go ahead.” I stuck my head through the ambulance door to see Stanley lying on a gurney with two attendants alongside. I said “Stanley, are you okay? He replied “Oh yeah. Everything’s fine. They’re taking me to the psych ward.” I said okay, wished him good luck, then left to retrieve the car.

I took a photo on the way. At least Stanley had the chance to finish his pasta and a hushpuppy or two!

I pulled the car around to the front of the hospital as my father and a hospice nurse brought my mother out in a wheel chair. Through the pain, her face lit up with a signature smile that said, “How wonderful to see you; all is well.”

A follow-up call to the Sandy Springs Police Department to check on Stanley was not returned, but I later found an incident report consistent with the date and time. The report didn’t give a name, but showed the offense as “Criminal Trespass.”

Incidentally, the word “hospital” is derived from 13th-century French ospital (shelter for the needy), and from the Latin hospitale (guest-house or inn). A hospital was once a place where hospitality was extended. My, how our institutions have changed.

An online search of Stanley Melvin produced the following:

Note that “Marine Private First Class Stanley T. Melvin” described above was born in Atlanta on February 17, 1947, but killed in action at the age of 20 on May 28, 1967.

I suppose it’s possible there were two Stanley Melvins born in Atlanta during the late 1940s who joined the Marines and served in Vietnam. After sharing this story with friends, one suggested Stanley was Jesus. Another imagined Stanley was either an angel, and/or a man who served in Stanley’s platoon. Expanding on this, she speculated that after an unsuccessful attempt to save his life, the brave Marine changed his name to honor Stanley’s spirit.

Stanley Melvin’s name also brought to mind Stanley Milgram, the famous psychologist who conducted the “Milgram Experiment” at Yale University and elsewhere in the early 1960s. Below is an excerpt from the Wikipedia article describing the experiment. Plenty more can be found online, including videos on YouTube.

The experiment was prompted by the (at the time) recently completed trial of Adolf Eichmann, a Nazi officer during World War II whose job involved transporting Jews to concentration camps, many of whom were later executed. Defending his actions prior to being convicted for crimes against humanity, Eichmann argued he was “just following orders.” In a follow-up plea for a pardon Eichmann wrote:

"There is a need to draw a line between the leaders responsible and the people like me forced to serve as mere instruments in the hands of the leaders... I was not a responsible leader, and as such do not feel myself guilty."

The Milgram experiment’s disturbing results indicated that only roughly one third of study participants (the “teachers”) were willing to disobey the authority figure’s instructions to shock the “learner” with ever increasing voltage to the point of death. Coincidentally(?), this one third is the same ratio of people who chose to extend compassion to the beaten-up man in the Parable of the Good Samaritan.

Milgram repeated the experiment over several years under a variety of circumstances. Among his findings was that proximity made a difference. The further removed the authority figure was from the teacher, the less inclined the teacher was to obey authority and deliver a fatal shock. Conversely, the more intimate the teacher was to the learner (for example, if they were in the same space, rather than separated by a wall) the greater the tendency of a participant to act in accordance with moral conscience and disobey authority.

Eichmann’s trial also influenced political theorist Hannah Arendt, herself a German-born Jew who escaped the Holocaust, and moved to the United States. The New Yorker magazine commissioned Arendt to cover the trial, and her articles were later incorporated into her 1963 book Eichmann in Jerusalem. Arendt concluded that many evils throughout history, and the Holocaust in particular, were not perpetrated by fanatics or sociopaths, but by ordinary people willing to unquestioningly accept an official’s instructions to “just follow orders.” She deemed such thoughtlessness “the banality of evil” and included the phrase in the book’s subtitle.

Arendt’s book prior to Eichmann was The Human Condition. In this work, published in 1958, Arendt distinguished the contemplative life from the active life, dividing the latter into labor, work, and action. Action, Arendt maintained, takes place in the public realm where connective ties emerge and excellence is recognized. She felt the modern age had produced an alienating public realm, one with a tendency to turn people inward, undermining the potential for relationship. Drawing on her observations, Arendt concluded:

“The public realm, as the common world, gathers us together and yet prevents us from falling over each other. What makes mass society so difficult to bear is not the number of people involved, but the fact that the world between them has lost its power to gather them together.”

It would seem Arendt was correct. The physical design of the modern public realm, with its emphasis on speedy efficiency, inhibits formation of the kind of healthy connection in which Arendt felt “great words and great deeds” might be realized. It also undermines the opportunity to be a neighbor.

Most can appreciate the importance of opportunity to advancing civilization. The ancient Greek poet, Alcaeus of Mytilene, understood it all too well. Around 600 B.C., he observed:

“Not houses finely roofed, not the stones of walls well built, nor canals nor dockyards make the city, but men able to use their opportunity."

Following that logic, perhaps the counterintuitive instructions of Jesus near the end of his Sermon on the Mount are worth taking to heart:

“Enter through the narrow gate. For wide is the gate and broad is the road that leads to destruction, and many enter through it. But small is the gate and narrow the road that leads to life. And only a few find it.” (Matthew 7:13-14)

In an isolating culture of hurriedness, which supports following authorized instructions through the wide gate and down the broad road, is it still possible to build a common world that provides the choice of loving one another?

Yes!

Thank God for Stanley and the one third! May they be forever blessed with the opportunity to be a neighbor!

Postscript: Faye Dyer Graham, definitely a one-thirder, passed away on April 8, 2018. Exiting the hospital after her procedure that spring day was the last time I saw my mom smile.

About the Author

Combining modern advances with time-tested urban principles, Vince Graham founded the traditional walking neighborhood of Newpoint in Beaufort, SC in 1991. Since that time he has participated in building eight other neighborhoods: the Village of Port Royal, Broad Street, I'On, Morris Square, Hammonds Ferry, Mixson, and Earl's Court in South Carolina; and East Beach in Virginia.

In addition to garnering numerous design and environmental stewardship awards, these neighborhoods have also been the subject of articles and stories in The Wall Street Journal, Builder, Landscape Architecture, and National Geographic magazines, Home and Garden Television, CNN, the BBC and more. Graham is a passionate advocate for advancing human-scaled urbanism, and has spoken at architectural and planning symposiums in Australia, Europe, and throughout the United States.