Financing Infrastructure with Value Capture: The Good, The Bad & The Ugly

Rick Rybeck is the Director of Just Economics, a firm that helps communities harmonize economic incentives with public policy objectives to build better places. We're pleased to share this guest article from him today. You can hear more from Rick in this 2014 episode of the Strong Towns Podcast.

President Trump’s infrastructure investment program was circulated recently. Page 24 of the program states that “value capture” financing will be required for any transit project to be eligible for federal funding assistance.

What is “value capture?” Unfortunately, the term has been poorly defined and applied by many so-called experts. Value capture is explained below along with some common misunderstandings about it.

Infrastructure Investments Create Land Value

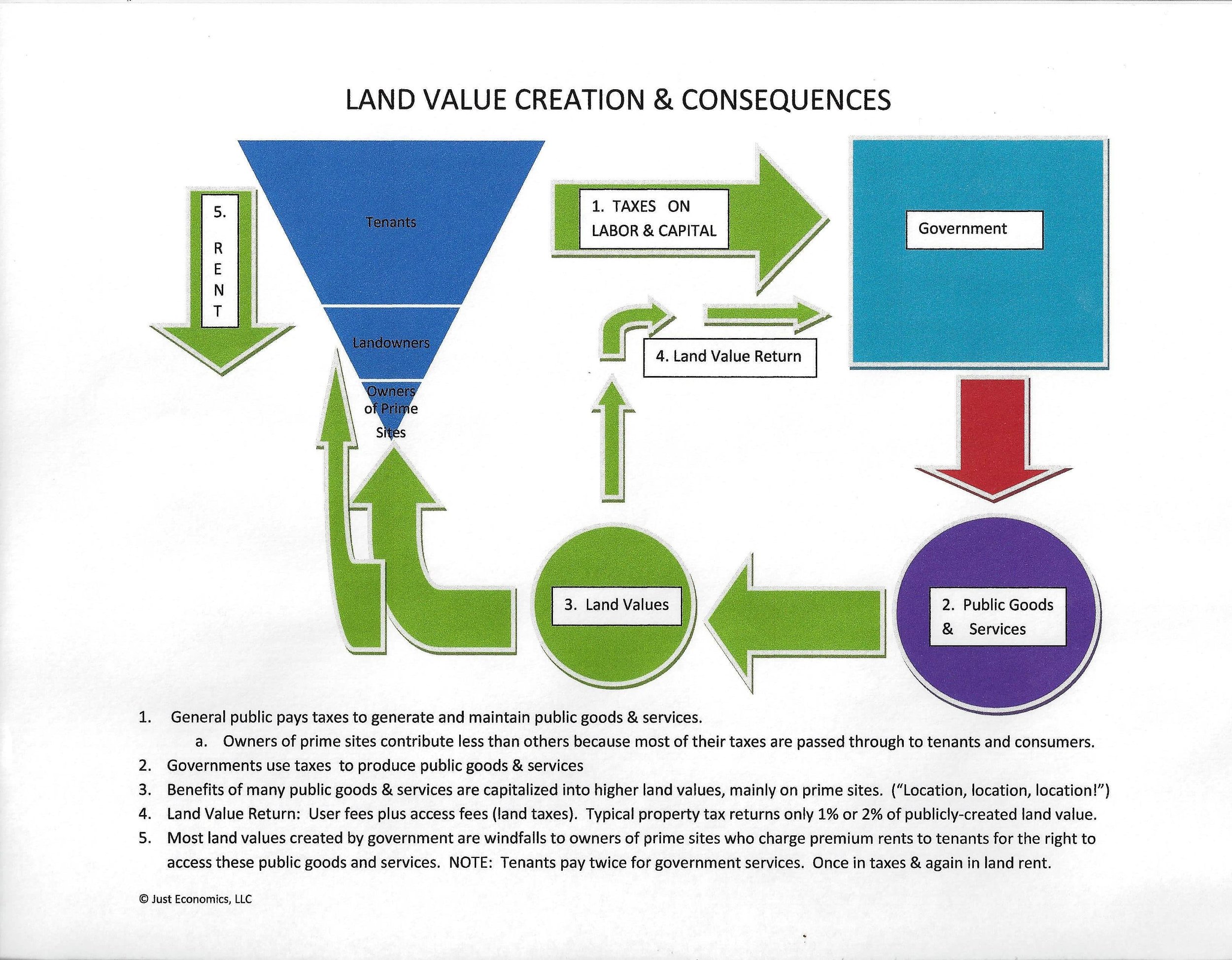

When infrastructure is well-designed and well-executed, it often increases the value and price of well-served locations. In urban areas, land value typically reflects the totality of all nearby amenities (and nuisances) that make a particular place suitable (or unsuitable) for residential, commercial or industrial purposes. Today, most of the land value created by new or improved infrastructure ends up as a windfall to those landowners who own the best-served land.

Private Appropriation of Publicly-Created Land Value

Because private landowners can appropriate publicly-created land values, most members of the public end up paying twice for infrastructure. First, they pay taxes to create or improve infrastructure. Second, if they want to take advantage of that infrastructure by locating their home or business nearby, they must pay a landowner a premium rent or price for the privilege of getting access to the infrastructure that their taxes created.

The ability of private landowners to appropriate publicly-created land value is the fuel behind land speculation – a parasitic activity that produces nothing of value. However, it tends to create an artificial scarcity of developable land and thereby inflates land prices. Inflated land prices drive residents and businesses away from the most valuable (and productive) land towards cheaper, but more remote (and less productive) sites. The use of sub-prime sites creates sprawl and reduces productivity. This harms the environment, requires costly infrastructure duplication and creates a drag on the economy. Land speculation can also create land price bubbles. When they burst, they drag the entire economy down as happened in 2008 and in every major recession and depression in our country’s history.

Land Value Return and Recycling

Private development under construction benefits from the nearby public rail station (Source: Montgomery County Planning Commission

Almost every community practices some form of land value return and recycling. For example, the traditional property tax is a tax applied to the assessed value of buildings and the assessed value of land. That portion of the property tax applied to land values returns these publicly-created values to the public sector where they can be recycled to help make infrastructure financially self-sustaining.

Unfortunately, most communities capture only a small fraction of the land value that they create. While property tax rates vary from place to place, in most communities they range between 1% and 2% of fair market value. If this stream of payments were collapsed into a single, one-time payment, it would be worth about $10 to $20 for every $100 of publicly-created land value. Thus, many communities are giving away 80% to 90% of the land value that they create. And, not surprisingly, the best-served land in most communities is owned by very wealthy individuals and corporations. So most communities are collecting taxes from everyone and enriching those who are already the most affluent and powerful. This is part of the dynamic of growing inequality.

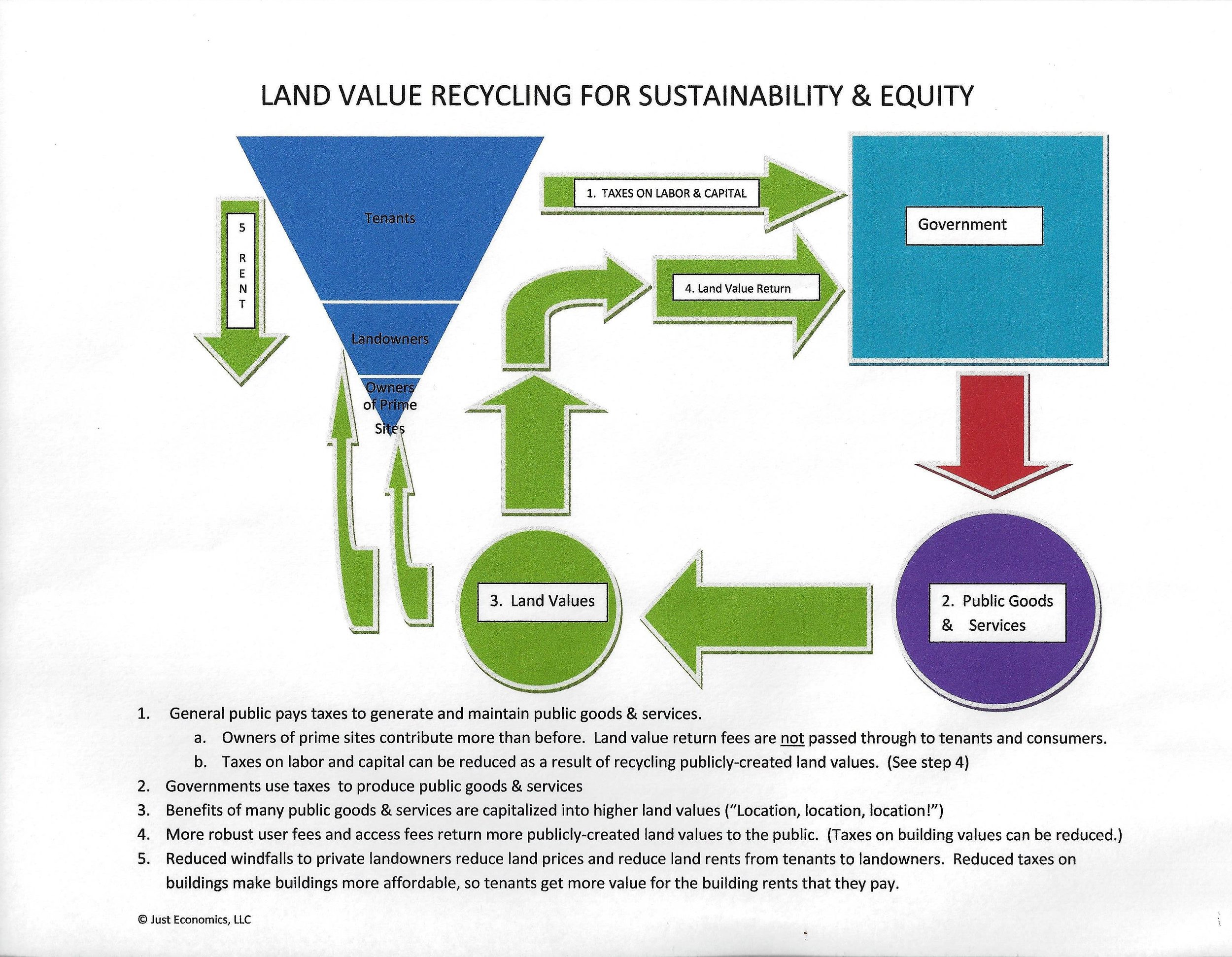

If communities were more vigorous in terms of land value return and recycling, the following results could be obtained:

- Land prices would moderate. (Land prices reflect the benefits that people expect to receive from owning it. Taxing land values more heavily reduces ownership benefits, thereby reducing what prospective purchasers will pay.)

- Because land values reflect the value of public infrastructure, landowners would pay in proportion to the public benefits that they receive. This is comprehensible, justifiable and equitable.

- Taxes would be highest where land values are highest. This would induce development on high-value sites (to generate income from which to pay the tax). High-value sites tend to be urban infill sites near infrastructure amenities (like transit), and this is where we want development to occur. Increasing development near infrastructure within cities and nearby suburbs reduces development pressure in outlying areas. This reduces sprawl. Compact cities require less infrastructure. They are more sustainable both environmentally and fiscally.

Using Land Value Returns to Reduce Other Taxes

As mentioned above, most publicly-created land value is a windfall to owners of prime sites. If more publicly-created land value was returned and recycled for public purposes, other taxes could be reduced. Indeed, some communities have pursued this approach by reducing the property tax rate applied to privately-created building values. A tax on the value of a building is a cost of production. Increasing the cost of production reduces the amount of buildings produced and increases the price of those that remain. So reducing the property tax applied to buildings makes them cheaper to build, improve and maintain. As can be inferred from above, the typical property tax applied to buildings has the economic impact of a 10% to 20% sales tax on construction labor and materials.

Thus, without increasing expenditures or reducing revenues, shifting the property tax off of privately-created building values and onto publicly-created land values can make buildings cheaper and land cheaper also. This would be good for residents and businesses alike and increase employment.

The Good, the Bad, the Ugly

Unfortunately, some people define “value capture,” as any tax or fee applied to real property without distinguishing whether the property being taxed is publicly-created or privately-created. This is not correct. Below are brief descriptions of various infrastructure funding mechanisms that have been referred to as "value capture."

Source: Johnny Sanphillippo

Development impact fees (DIFs) are one-time payments created to defray the cost of new or improved infrastructure required by new development (as determined by a formula). They are applied to privately-created building values. Thus, DIFs transfer privately-created value to the public sector. DIFs are more aptly characterized as “cost reimbursement” than as “value capture.” Note: A DIF makes development more expensive, thereby reducing the amount and raising its price. Would a community want to reduce development next to transit and make it more expensive? In this circumstance, a DIF would be counter-productive.

Exactions are negotiated, in-kind infrastructure donations required of developers in exchange for development permits. Like development impact fees, they should be based upon the infrastructure needs generated by the new development and are tied to the value of buildings. Exactions also transfer privately-created value to the public sector and are more aptly characterized as “cost avoidance” than as “value capture.”

Tax Increment Financing (TIF) is often referred to as value capture. TIFs are different in different jurisdictions. But most of them operate as follows:

- A new infrastructure project is planned that will benefit nearby properties.

- The legislature cannot justify spending everybody’s tax dollars to benefit a few property owners. So, instead of putting this project in the budget, they create an assumption. The assumption is that, but for the new infrastructure project, tax revenues in a defined area would be static.

- One or more revenue streams in the defined area are benchmarked before the infrastructure project is started.

- Thereafter, any increased revenue within the defined district is assumed to be the direct result of the infrastructure project. This “tax increment” does not go to the general fund, but is set aside into a dedicated account to pay for the infrastructure project.

NOTE: Under most TIFs, property owners pay the same rate of tax as they would if there was no TIF. So there is no more (and no less) value capture after the TIF is created than there was before. Thus TIF is more aptly described as “revenue segregation” than as “value capture.”

Transportation Utility Fees (TUFs) are generally assessed against building users (tenants) based upon assumed trip generation associated with various uses (restaurants, retail stores, offices, theaters, apartments, etc.). Each use has an estimated trip generation per square foot of developed space. Thus, each space user is assessed a fee (based on type of use and total square footage) that is intended to represent their impact on the transportation system. Thus TUFs are based on privately-created value – the type and size of occupied building spaces. Although a TUF might resemble a user fee, it is not. The fee is based on estimatedtrip generation and those who must pay have no opportunity to change their financial liability by changing their actual use of (or impact on) the transportation system. Because TUFs will be an additional expense for those who occupy space within a defined TUF district, it will tend to depress land values and rents within that area. If commercial tenants are locked into long-term leases when a TUF is applied, then these businesses might become less cost-competitive with rival businesses located outside of the TUF area. Depending on the level of the fee and the intensity of the competition, this could lead to lower profits and/or business closings within the TUF area. Unlike land value return, the cost of TUFs will be passed along to customers & employees. Thus, TUF is more aptly described as “value transfer” than as “value capture.”

Sale or Lease of Public Land or Air Rights if conducted through an arms-length transaction at market rates, will be a form of “value-capture.” Sale of public land or air rights results in a one-time infusion of cash. If public sector infrastructure improvements enhance that land after the sale, that enhancement will largely be a windfall to the subsequent private owner. Leasing of public land or air rights results in a continual stream of revenue and retains public control in the long term. Furthermore, if public sector infrastructure improvements enhance that land in the future, that enhanced value can be returned and recycled by future rent increases.

Joint development is a process whereby a private developer creates or pays for a public facility (like a transit station) in exchange for permission to create a private development above or adjacent to that public facility. If the infrastructure created by the developer has a cost roughly equivalent to the land value consumed by the private developer for its private development, then this too would be aptly characterized as “value capture.”

Land value tax is a property tax applied only to land value. As such, this is clearly land value return and recycling. This is accurately characterized as “value capture.” In the US, pure land value taxes are rare. However some communities employ a "split-rate property tax” whereby a higher tax rate is applied to land values and a lower tax rate is applied to building values.

Special assessments are additional property taxes levied within a defined area where new or improved infrastructure benefits those properties. If the special assessment is based solely upon land value, then it is “value capture.” If the special assessment is based solely upon building value, then it is “value transfer.” If the special assessment is applied to both land and building values, then it is both “value capture” and “value transfer.”

These distinctions are not trivial. How we raise money for infrastructure is as important as how much we raise. The distinction between funding techniques that utilize land value return and recycling (LVRR) and those that do not is illustrated below. This graphic depicts a transit station (T) with a vacant lot to the left and a developed lot to the right.

The transit station enhances the value of both lots equally. The owner of the vacant lot pays nothing under a DIF approach. Under LVRR, both owners pay the same fee for the same benefit. Unlike a DIF, LVRR results in no economic penalty for constructing, improving or maintaining a building adjacent to the transit stop.

---

All of the eight infrastructure funding techniques described above might be appropriate under certain circumstances. For example, employing a development impact fee might be appropriate in rural and exurban areas where necessary infrastructure is lacking. Raising the cost of development in these areas might help steer development back to areas where necessary infrastructure already exists and thereby help curb urban sprawl. Likewise, employing land value return & recycling in an urban area would help ensure more intense and more affordable development near existing infrastructure and thereby help curb urban sprawl also.

Today, “no good deed goes unpunished.” Infrastructure improvements are often accompanied by adverse, unintended consequences such as urban sprawl, higher real estate prices and displacement of low-income households. If properly designed and implemented, more robust land value return and recycling (or “land value capture”) combined with lower taxes on buildings can fund our infrastructure needs while avoiding these negative consequences.

Returning to the draft infrastructure investment outline, most infrastructure will increase the value of well-served land. Therefore, requiring “value capture” financing (if it is defined as “land value return and recycling”) would be an appropriate requirement for most infrastructure projects – and not merely for transit projects alone.

(Top photo source: Sounderbruce)