What if you and your neighbors redesigned your town's worst intersection?

We’ve all got one. That particularly awful intersection in your neighborhood that you can’t avoid passing through every single day. And almost all your neighbors hate it too: every other week, it seems like someone else has crashed their car, or narrowly missed being hit on their bike, or had to sprint to make a too-short walk signal — and every once in a while, something far worse happens.

You may not know what to do about it. But you know that if you and your neighbors had any kind of a say, that intersection would look a whole lot different.

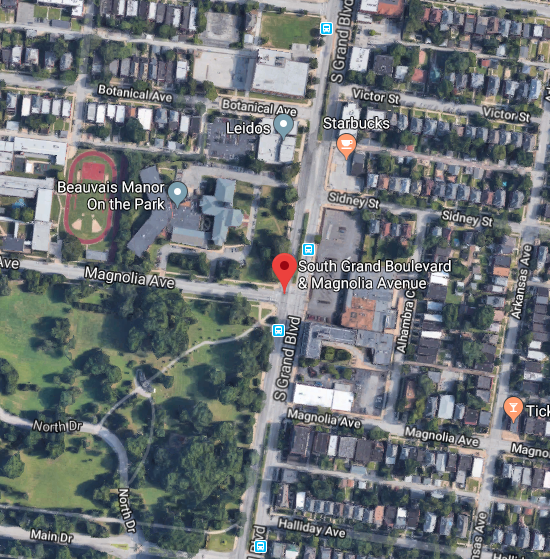

For many residents of my St. Louis neighborhood, that intersection is the northernmost divide of Magnolia and Grand.

Magnolia and Grand represents the intersection not just of two major streets, but of the many ways that the St. Louisans around it live. It's a five lane stroad that the city has done its best to turn into a complete street, maintaining a major bus route, a painted bike lane, and generous sidewalks.

It sits on the dividing line between two of the city's most popular mixed-residential neighborhoods (Shaw to the north and Tower Grove East to the east,) and it's just 0.3 miles away from the South Grand business district, home to a critical mass of our city's best international restaurants, groceries and shops. And closer in, the intersection is immediately adjacent to not one, but two retirement communities, the state's school for the blind, a preschool, a grocery store, and a major city park. (See locations mentioned on the map below.)

Stand on any corner of Magnolia and Grand on a Saturday morning, and you should be able to see the full diversity of our city — drivers intermingling with bikers and pedestrians, people of all ages and levels of mobility navigating a bustling intersection with ease.

But that's not always what you see.

For years, this intersection has had a reputation not as a multi-modal melting pot, but as the site of daily red-light runs, close calls with pedestrians, and even tragedy, such as the 2003 death of School for the Blind student-athlete DeJuan Banks. In an informal poll of residents of Tower Grove East, Shaw and nearby Fox Park, only 14.81% of respondents rated Magnolia and Grand as "safe" or "very safe."

At Strong Towns, we believe we need to really sit down and listen to what our citizens have to say about how they experience their streets. Here's what four users of this intersection told me about how they experience Magnolia and Grand, and how they'd shape its future.

Princilla Gold.

The Driver

In auto-oriented St. Louis, it's no surprise that most of the people I spoke with tend to drive cars as their primary mode of transportation. But that doesn't mean that the intersection is meeting their needs.

Fox Park resident Princilla Gold learned that first hand — she experienced a car crash at Magnolia and Grand. "There was a lot of traffic — that’s usually how it is at that part of Grand," Princilla says. "I was driving southbound, and another car was trying to turn off from Magnolia, heading east... An ambulance was starting to come up [behind them], and I think the driver kind of panicked about what to do, and so instead of pulling over, they pulled out into the middle of the street and hit me."

It might seem like a screaming ambulance is an outlier scenario that could easily explain a crash like this. But Gold and many of her fellow residents find the intersection chaotic even when there's no emergency. 41% of survey respondents pointed out that the Ruler Foods grocery store parking lot has a south Grand entrance that empties virtually into the intersection; it has its own traffic signal, but it's confusing to drivers on the roads.

Others cited that familiar drivers traveling south on Grand anticipate that the street splits into straight and turn only-lanes not far past the light, so these cars often start jockeying to get into position in the middle of the intersection, startling the unfamiliar. "The streets of South City are already difficult, and there isn’t clear direction on how to navigate that particular intersection," Princilla said. "If you're from out of town, or even if you’re a seasoned driver in St. Louis, it’s just problematic."

She also expressed concern for how confused drivers interact with non-drivers — particularly residents of the neighboring retirement homes. "[I see] elderly people trying to cross that street all the time," she says. "It’s scary, because they just can’t move that fast.”

As a non-planner — Gold is a benefits advocate in the insurance industry, as well as a mom — she isn't sure how the intersection might be redesigned. In the meantime, she's just not taking any chances. "After that accident, I try to be super cautious in that area," Gold says. "I try to stay away from it if I can, even if [my son’s] not in the car with me.”

Devin Durdin

The Public Transit Supporter

These days, Devin Durdin is mostly a driver as well. But as a former heavy user of public transit — Durdin, 34, didn't get a car until she was 27 — she tries to see Magnolia and Grand through a non-driver's eyes.

"I took the bus for years, so I have kind of a soft spot for pedestrians and bikes and motorcycles. My mom and dad both ride motorcycles," Durdin says. "And I’m well aware of how cars can be just oblivious to pedestrians. I know [when I'm walking in a crosswalk,] I’m one of those people who’s very like, this space is for me, and your car is violating it."

And Durdin has witnessed more than her fair share of close calls between people and cars on Grand, which is flanked by stops for the #70 city bus line.

"That light, because it’s near the blind school, it has sounds and whatnot," Durdin says, referring to accessible pedestrian signals at all four of the crosswalks. "But that isn't enough. Sometimes I think the lights aren’t long enough. [Walkers] get halfway across, and the hand will have already come up. And of course, people will have pulled into the pedestrian section of the street by then."

Durdin's not a planning professional — she's pregnant with her first child and currently preparing to be a stay at home mom — but she knows enough about the functionality of her streets to make confident recommendations for how they could be redesigned.

"I think the crosswalk needs to be painted better," she says. "And it needs another thick white line that says hey, your car belongs behind here, not in front of it or over it.”

Catherine Gilbert

The Pedestrian

As a pedestrian and as a professional urban planner, Catherine Gilbert agrees with Durdin that better pedestrian markings are a vital first step for the intersection. And as a pro, she has a few specific suggestions that she'll give the city for free.

"[The crosswalks] should be zebra striped and be much more noticeable, so cars have to stop behind them." Gilbert told me via email. "Right now, they appear to be suggestions."

Gilbert thinks this type of seemingly "suggestive" design isn't helping cyclists at Magnolia and Grand, either. She's particularly concerned about the sign that marks southbound Grand as no right on red — a sign that drivers typically don't even notice until they've pulled directly into the bike lane to try to make the turn.

"By then, some people still go on red, and some don't," Gilbert pointed out, which makes an already chaotic intersection even more unpredictable. "If you created a green box at the intersection indicating where bikes would be, it would make it harder for cars to sneak up on the right and ensure bikes remain safe."

Whatever the city does next, Catherine recognizes that simple signage almost certainly won't be enough to solve the problem. And she probably doesn't recommend this traffic calming approach she once happened across when out on a run in a different part of St. Louis: a hand-drawn yard sign that just says "SLOW."

Courtney Cushard

The Cyclist

Courtney Cushard is also an athlete — she's a state champion cross racing champion, and an avid bike commuter (and, full disclosure, a dear friend of mine). But she doesn't think Grand and Magnolia is safe even for the fastest cyclist — much less citizens who need a little more time to make their way across.

When I asked Courtney via email whether she found the intersection problematic, dangerous, or difficult to use, Courtney said "Yes to all of the above." She also added that cyclists have unique challenges when traveling down the Grand Avenue bike lane, noting that "the pavement in the bike lanes is poorly maintained and thus dangerous for bikes and treacherous for cars. The bike lanes are very narrow at this point on Grand and, with auto traffic moving so quickly and often over the speed limit, having unprotected bike lanes at the major access point to a popular park is quite dangerous."

Like all four of the residents I spoke to in depth, Courtney also noted that the mid-intersection entrance to Ruler foods is hugely dangerous for all modes of transport. But Courtney also pointed out something else that's just as problematic about the entrance: how steep it is.

"The grade change if the parking lot driveway is very dangerous for cars, cyclists, and pedestrians, and completely inaccessible for anyone with any kind of impairment or disability," Cushard added. "When icy, the slope of the driveway can cause cars to slide into the sidewalk, bike lane, or auto lane, creating a very dangerous situation... It needs to be made ADA compliant."

Courtney coordinates a study abroad program at a university, but as both a year-round cyclist and as someone who holds a master's in urban design, she's particularly attuned to how the intersection can become more dangerous under changing conditions. Aside from icy weather, she cited the intersection's poor night lighting, as well as how the planted medians to the north of the intersection limit visibility in the spring.

"With a school and senior living center so close, this intersection needs significant improvements for it to be safe to all users including physically impaired folks, children, and families."

Can Citizens Really Design a Public Space?

It's not hard to understand why so many of our cities don't seek enough citizen input when it comes to street design. The vast majority of the neighbors I spoke with weren't professional planners, designers, or engineers, and many didn't feel comfortable providing solutions to the problems they experienced in the intersection every day. And it wasn't easy or efficient to gather the solutions and perspectives that I did—this, by far, was the most time-consuming article I've ever written for Strong Towns, even though my survey was far from comprehensive.

But the wealth of knowledge that I got even from this miniature, completely unscientific poll of my neighbors astounded me. Collectively, the residents near Grand and Magnolia identified persistent, fixable problems:

- the mid-intersection Ruler Foods entrance (42%)

- a short walk signal (11%)

- cars driving into a painted bike lane (11%)

They also came up with a few easy solutions:

- closing or limiting entrance to that problematic driveway (42%)

- increasing crosswalk intervals and length (17%)

- improving pedestrian markings (15%).

They clearly shared their diverse experiences, needs, and dreams for this shared space, whether or not they had the vocabulary necessary to ask for a specific technical solution. And nearly everyone expressed ideas and concern not just for how they use the intersection, but how their entire community does.

Now imagine if I'd had just a little bit more, time, resources, money, and knowledge to do this work. Imagine if a few more neighbors did the same, and if maybe a few of our local leaders got on board.

Now let's dream big: imagine if all of our leaders committed the time to really listen to citizens, translate their ideas into creative solutions, and then circle back and make sure they'd accurately served their communities' needs. Imagine if we really took the time to experiment on our streets, tweaking and trying new things until we got it just right.

It'd be a major shift from how most of our cities work now. But it'd be a truly Strong Towns-style approach.