How do we define affordable housing?

Today's guest article comes from Todd Litman, founder and executive director of the Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Unaffordability is a major problem, particularly in attractive and economically successful communities. Most households spend more on housing and transportation that is considered affordable. This is a great challenge and a great opportunity: increasing affordable housing supply makes communities more inclusive, and increases economic opportunity, freedom and happiness.

Living in a popular, dense urban neighborhood isn't so expensive compared to suburban living when you factor in savings on home maintenance, utilities and transportation. (Source: Johnny Sanphillippo)

How affordability is defined and measured can affect which solutions are implemented. Measured one way, a particular solution may seem effective and beneficial, but measured another it may seem wasteful and harmful overall. Let me describe a specific example.

The latest International Housing Affordability Survey (IHAS) was released late January. It rates Vancouver the third most unaffordable city in the world, blames this entirely on the region’s urban containment policies, and so recommends more urban fringe development. The Survey is heavily promoted by its authors and widely reported by media, with little critical analysis. I analyzed its methods and recommendations, and recently released my findings in a new report, True Affordability: Critiquing the International Housing Affordability Survey. Let me share some highlights of my study and hope that you will read the full Critique for more details.

My overall conclusion is that the IHAS is propaganda, intended to support a pro-suburban political agenda rather than provide objective guidance. The IHAS’s analysis methods are biased and many of its recommendations are unsupported by research. The authors, Wendell Cox and Hugh Pavletich, are either very poor researchers or intentionally misrepresent key issue.

Experts recommend measuring affordability based on the portion of household budgets needed to purchase basic goods and services. Affordability was originally defined as households being able to spend up to 30% of their budgets on housing, but since households often make trade-offs between housing and transportation costs, experts now define affordability as households spending up to 45% of their budgets on housing and transport combined. This recognizes that a cheap house is not truly affordable if it has high transport costs, and households can rationally spend more for more accessible housing with more affordable transport.

The IHAS analysis methods have various structural problems which bias results:

- The IHAS evaluates housing affordability using Median Multiples, which measure the ratio of median house prices to median household incomes. This only considers house purchase prices, ignoring other shelter costs such as maintenance, utilities and property taxes, and it ignores transportation costs. The costs the IHAS considers are smaller on average than the costs it ignores. Since detached, urban fringe housing tends to have higher maintenance, utility and transport costs, this exaggerates the affordability of urban expansion and underestimates the affordability of compact infill.

- It overlooks or under-samples affordable housing types including secondary suites, rentals, subsidized housing, and condominiums. This exaggerates unaffordability where such housing is common.

- It includes a limited set of regions. In some countries it includes both small and large cities, but in Asia it only includes large and expensive cities such as Hong Kong, Singapore and Tokyo. This exaggerates unaffordability in those countries.

- It fails to account for factors that affect regional affordability such as population and economic growth, incomes and geographic constraints. This exaggerates unaffordability in attractive, economically successful and geographically constrained regions.

- It measures entire regions, ignoring within-region affordability variations. Central neighborhoods are generally most affordable overall, considering total housing and transportation costs, and offer other benefits such as commute time savings and health benefits.

These biases make detached urban-fringe housing seem more affordable, and compact infill housing seem less affordable, than households actually experience.

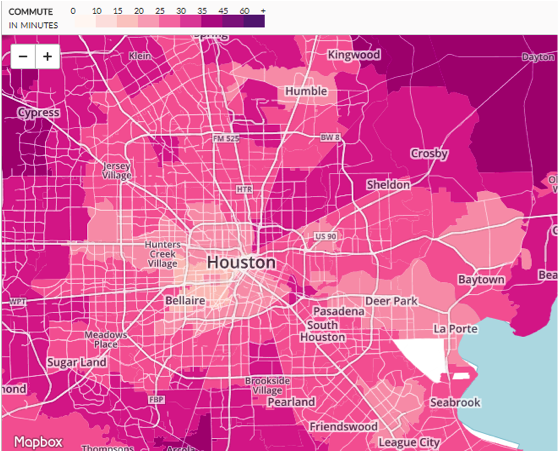

Although Houston and Atlanta households spend relatively little on housing, this is offset by their high transport costs, making them least affordable of all regions included in the U.S. Consumer Expenditure Survey. (Source)

More comprehensive analysis leads to different conclusions about unaffordability problems and appropriate solutions. For example, the IHAS ranks Atlanta and Houston as more affordable than Seattle and Washington DC, but when evaluated using actual consumer expenditure data the ranking reverse, because the sprawled regions’ low housing costs are more than offset by their higher maintenance, utility and transport costs, making the sprawled regions the least affordable of the 22 regions included in the U.S. Consumer Expenditure Survey, as indicated in the chart above.

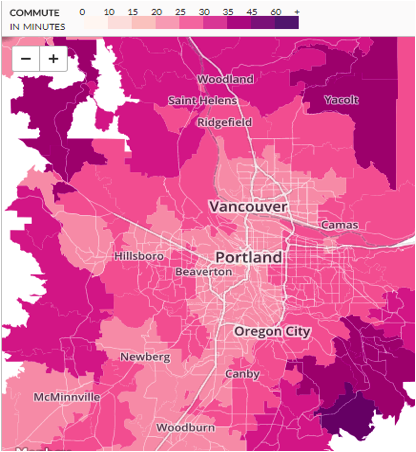

IHAS ignores many benefits of living in a walkable urban neighborhood. It claims that suburban design reduces travel time costs, but within virtually all regions, more central neighborhood residents have better access to jobs and services, and shorter duration commutes than urban fringe residents, as indicated below. This is particularly true for non-drivers, who have far more independent mobility and therefore greater economic opportunities in central urban neighborhood. The IHAS ignores these benefits.

Residents of more central urban neighborhoods tend to have much shorter commutes than at the urban fringe.

The IHAS claims with great certitude but no real evidence that urban containment policies are the primary cause of urban housing price increases. In fact, even studies it cites indicate that restrictions on urban infill are much more common and costly than urban expansion restrictions, as illustrated below, and therefore a much larger cause of unaffordability. Reducing these constraints on affordable infill, so more households can find suitable housing in walkable urban neighborhoods, is the key to creating truly inclusive communities.

Most zoning codes and development policies limit urban infill. Few jurisdictions have urban containment policies, and these generally allow some urban fringe development.(Source)

More objective analysis indicates that housing unaffordability results from a combination of population and economic growth, plus constraints on both urban expansion and infill. Expansion may be appropriate in cities with abundant land nearby, but incurs high costs to residents and communities. As a result, there are good reasons to favor infill with policies that increase affordable housing in existing urban areas.

The IHAS makes recommendations unsupported by research. It advocates urban expansion but ignores the additional costs of suburban design to residents and communities. The IHAS ignores the mobility needs of people who cannot, should not or prefer not to drive, and therefore the isolation and higher transport costs they experience in automobile-dependent, urban-fringe areas. It claims incorrectly that sprawl benefits disadvantaged people. Good research indicates the opposite: physically, economically and socially disadvantaged people have more independence, better economic opportunities, and better outcomes in walkable urban neighborhoods than in automobile-dependent urban fringe areas.

Although the IHAS is presented as objective research, it does not reflect professional standards: its analysis is not transparent, it misrepresents key issues, fails to respond to legitimate criticism, and lacks peer review. The IHAS is propaganda, intended to support a political agenda. It is important to consider these biases and misrepresentations when using information from the IHAS.

(Top photo by Kimson Doan)

About the author

Todd Litman is founder and executive director of the Victoria Transport Policy Institute, an independent research organization dedicated to developing innovative solutions to transport problems. His work helps expand the range of impacts and options considered in transportation decision-making, improve evaluation methods, and make specialized technical concepts accessible to a larger audience. His research is used worldwide in transport planning and policy analysis. Mr. Litman has worked as a research and planning consultant for a diverse range of clients, including government agencies, professional organizations, developers and non- government organizations. He has worked in more than two dozen countries, on every continent except Antarctica. Mr. Litman is a frequent speaker at conferences and workshops. His presentations range from technical and practical to humorous and inspirational. He regularly blogs on the Planetizen website. He is active in several professional organizations including the Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE) and the Transportation Research Board (TRB, a section of U.S. National Academy of Sciences).

With interest rates rising, the cost and availability of housing are becoming increasingly popular topics of debate. But most of these discussions fail to challenge the root of the issue: the absurdity of mortgages as an investment vehicle.