Striding Toward Walkability? 5 Insights About Walkable Urban Places

In the years immediately after the last housing market crash, a narrative took hold in mainstream media that there had been an inexorable, immediate, and permanent change in how we build our cities. Some writers went so far as to proclaim The End™ of suburbia, gravely or gleefully depending on the audience. The auto-oriented development pattern had been exposed as a Ponzi Scheme, and now we were forever done building Taco John’s and Walmarts at interstate off-ramps.

Of course, change in an entire continent’s development pattern—the result of a devilishly complex set of institutions, incentives, and feedback loops—is never going to be sudden and stark, barring a complete collapse the likes of which would make the Great Recession look mild.

And so naturally, the pendulum has swung back, in part due to public policy choices. Instead of reckoning honestly with the effects of a debt-driven, ultimately insolvent pattern of growth on our economy and society, we did what we could to keep the party going, and going it is. And so now, construction is back up (albeit nowhere near pre-2008 levels, especially where housing is concerned), including in car-oriented suburban areas. And now there’s a new think-piece every month or so declaring that “the suburbs reign supreme again” or “the back-to-the-city movement is over.”

“Suburbs versus cities” horse-race journalism is a particularly irritating brand of journalism for anyone who cares about precision of language, because that precision is pretty much never there. Most analyses look at the county level, for example, which is all but meaningless. In almost every major metro area, urban “core” counties (and even core cities) contain both very urban areas and very suburban areas in terms of their built form.

Our urban areas are still overwhelmingly automobile-oriented.

Rather than where we’ve built, I’m more interested in reading a study about what we’ve built, and especially when its lead authors are people I know to be smart and incisive. Foot Traffic Ahead: Ranking Walkable Urbanism in America’s Largest Metros by the George Washington University Center for Real Estate and Urban Analysis (along with Smart Growth America and some other partners) promised to be that kind of study: a look at trends in the actual development pattern of America’s metro areas, as far as walkable versus unwalkable places.

The study is long, and comes with a lot of caveats. Turns out it’s really hard to quantify this stuff, and even harder to do it rigorously in a way that also allows for a big-data approach. After all, the best way to know a walkable place is to, well, get out of your car and walk around it. Absent the ability to do that in the 761 walkable neighborhoods the authors catalogue, they settle for the use of WalkScore. A walkable urban place, or WalkUP in the study’s lingo, is defined by a critical mass of retail or office space combined with a Walk Score greater than 70 out of 100, a methodology borrowed from the Brookings Institution.

WalkScore is a far-from-perfect metric: it’s ultimately an algorithm making its best guess. But it does take into account some of the basic features of walkability, most notably whether the essentials of everyday life—the ability to buy groceries, for example—are available within an easy walk of a location.

The result is a study that is worth reading, which generally reinforces what we at Strong Towns have previously observed to be true: mixed-use, walkable neighborhoods have enduring appeal, are more financially productive than auto-oriented places… and we still don’t allow nearly enough of them to be built.

5 Take-Aways about Walkable Places From Foot Traffic Ahead

1. The momentum is toward walkable urban places in every metropolitan area.

The WalkUP office and rental multi-family product types in all 30 of the metro areas have had market share gains of 130 percent in this real estate cycle relative to the 2010 market share base. This means that drivable sub-urban real estate products have been losing market share to walkable urban real estate products during this economic cycle. In the case of Pittsburgh, Boston, and Denver, walkable urban product market share has been nearly or even above 100 percent of the net absorption in these two product types, meaning drivable sub-urban occupancy has added no net absorption or even lost absolute occupancy since 2010, as shown by the growing vacancies in business parks and regional malls.

This doesn’t mean we’re not still building auto-oriented development—or even more auto-oriented development in absolute quantity, because American metro areas are overwhelmingly dominated by suburban, auto-centric land use. If 80% of retail in a city exists in driveable shopping plazas and strip malls, for example, it would be possible to build twice as much retail in such auto-centric formats as in walkable formats, and the overall market share for walkable development would still increase.

2. Walkable places are, indeed, more financially productive.

The weighted rent per square foot premium for WalkUP office, retail, and multi-family product types is 75 percent over the balance of the metro inventory, nearly twice the rent in drivable sub-urban places. This rent premium for walkable urbanism has increased by 19 percentage points during the course of the cycle beginning in 2010, indicating that the premium still may not have reached its peak. From other research in select metropolitan areas, we have found that there can be a capitalization rate premium for walkable urban income-producing real estate of between 30 to 50 percent. This means that the value of a walkable urban square foot is more than that of a drivable suburban square foot.

These places are the absolute powerhouses of our regional economies, in regions with dense urban centers and regions known for spread-out development alike:

At one end of the walkable urban spectrum, metro New York City, the 2016 WalkUP Wake-Up Call analysis of the New York metro found that WalkUPs comprised only 0.5 percent of the metro’s land area. At the same time, WalkUPs contributed 55.6 percent of the region’s metropolitan gross regional product (GRP) and contained 38 percent of the region’s real estate market value.

At the other end of the walkable urban spectrum, the Dallas-Fort Worth metro, a region in the Sun Belt defined by its sprawling, low-density development, WalkUPs are also disproportionately contributing to the region’s economy. In the 2019 WalkUP Wake-Up Call analysis of the Dallas-Fort Worth metro area, the 38 WalkUPs comprised 0.10 percent of the metro area’s land, but generated 12 percent of metropolitan GRP.

3. There’s still a dramatic shortage of walkable places. (And that shortage drives up the price.)

The high price of walkable urban places isn’t just a matter of intrinsic desirability. It’s also a matter of scarcity: strong demand for real-estate (both residential and commercial) in walkable neighborhoods, coupled with extremely inadequate supply in most metro areas. Housing in walkable areas costs more—a lot more—which is indicative of strong demand and limited supply:

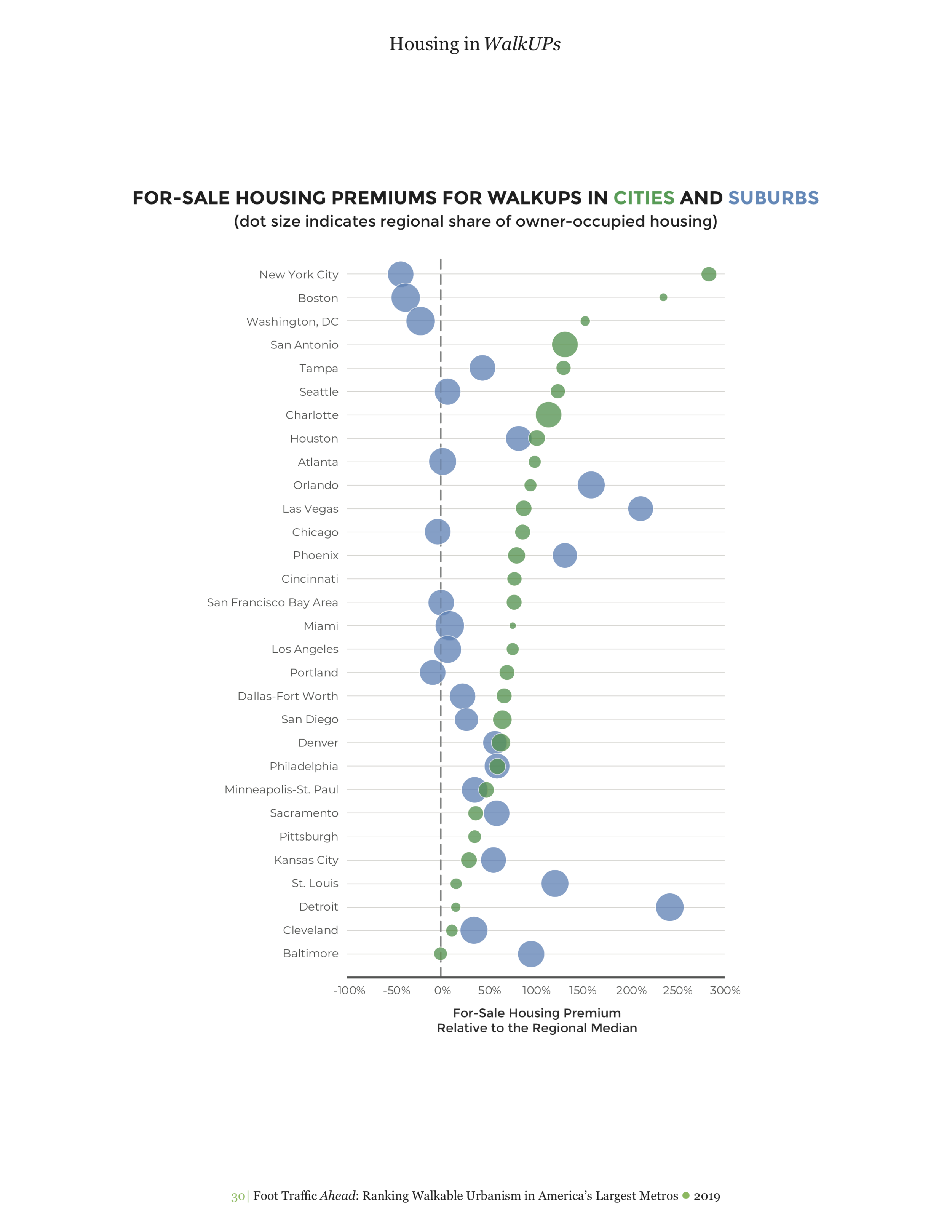

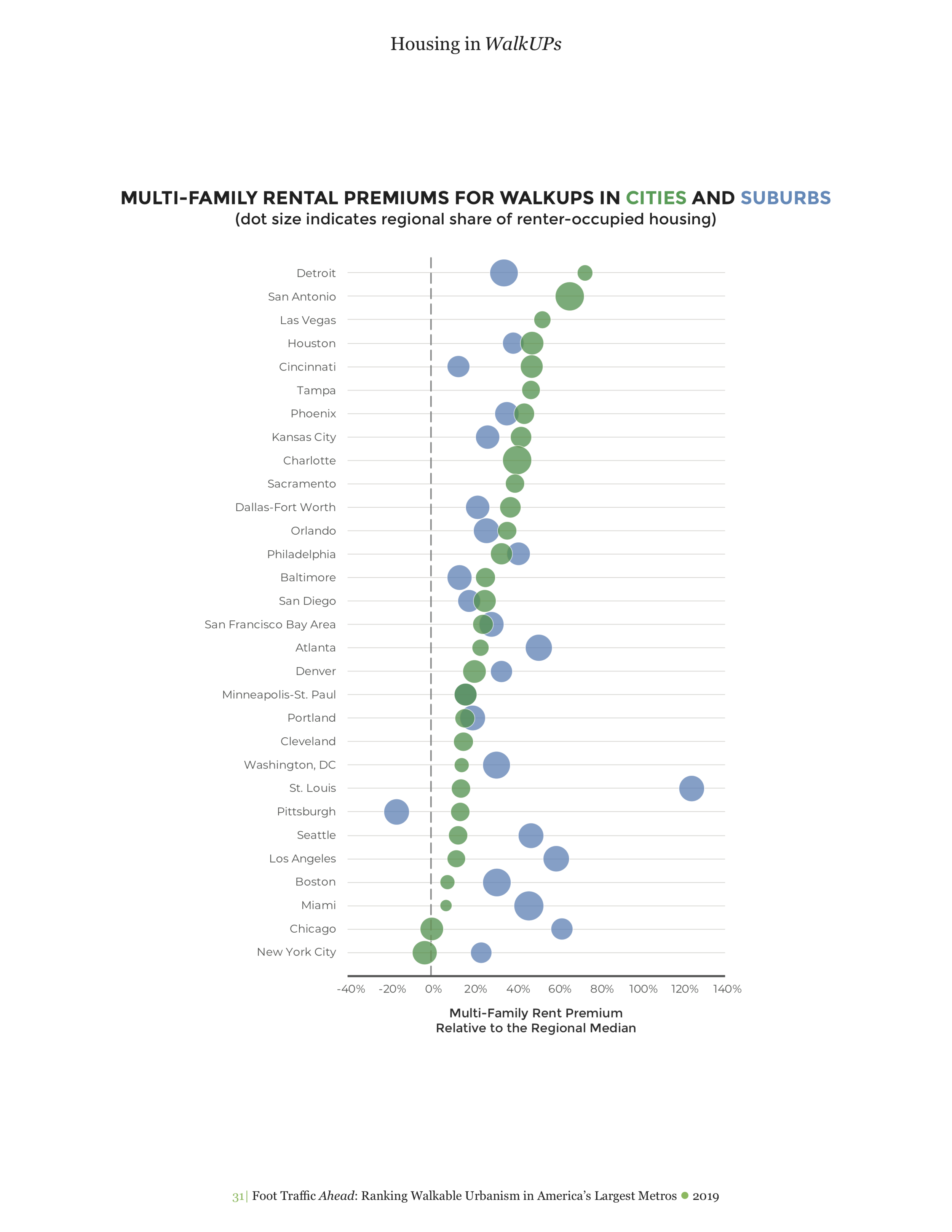

The average for-sale per square foot premium was 90 percent, or the estimated equivalent of an additional $174 per square foot in home sale price when located in a WalkUP. The average rental premium was 46 percent, ranging from 27 percent in Denver to 88 percent in Detroit. For-sale premiums varied more dramatically by metro, with Boston leading the country at a whopping 223 percent estimated premium to buy a home in a WalkUP, contrasted with the relative bargains still available in Baltimore, where a home in a WalkUP costs only an estimated 17 percent more than the regional median.

City Observatory has written before about this national “shortage of cities.” A major root cause: zoning restrictions that ban apartments or any sort of missing middle housing, and other rules, such as parking minimums, that require so much land to be devoted to accommodating cars as to make it effectively illegal in many places to actually build walkable development.

The Foot Traffic study suggests that, in metro areas where the premium for walkable development is still increasing—i.e. the gap between the high price of walkable real estate and the lower price of driveable real estate is growing—that suggests that pent-up demand continues to drive up the price of such places.

4. Walkability is good for affordability in one crucial way, despite the premium you pay.

According to the study authors, the price (and thus tax-base) premium for walkable areas does not have to mean that such areas are exclusive or inaccessible to the majority of people, because living in such a place comes with its own benefit to the household bottom line: low transportation costs. This is reflected in the study’s “Social Equity Index”:

It is counter-intuitive but the upper right hand corner of the scatterplot contains the metros with both the highest economic performance for their WalkUPs and the highest social equity for lower income households. While the “rent is too damn high” in nearly every metro for low income households, it is partially offset by lower household transportation costs. The majority of the WalkUPs in these six highest ranked metros (green dots) on both economic and social equity metrics have multiple transportation options, in addition to cars and trucks, which allow for lower income households to participate in society without maintaining a fleet of vehicles. By shifting household income from ownership and maintenance of automobiles (always depreciable assets) to housing (generally an appreciative asset), there is a far better opportunity to build household wealth. By dropping one car out of a household budget (AAA estimates the cost of car ownership averages $8,849 per year), a family can increase their mortgage capacity by approximately $150,000 at a 4 percent mortgage rate.

5. A lot of walkable urbanism is located in suburbs, especially in some regions you might not expect.

Here’s where the “most growth is in suburbs, not cities” analyses really fall short: in the 2010s, America’s suburbs have urbanized to an unprecedented extent. This is not a universal trend, but it is a significant one, especially in certain metro areas. The Boston and Washington, D.C. metros, well known for compact development, have nearly half of their “WalkUPs” located in suburbs; but so, less intuitively, does Miami. Other cities, such as Dallas and Atlanta, are surrounded by suburbs with traditional town centers that are urbanizing and becoming walkable cores in their own right.

Is the long-foretold End of the Suburbs coming to pass anywhere? In an interesting aside, the authors conclude that if it is, that somewhere is metropolitan Boston:

99 percent of office and multi-family rental net absorption has been in WalkUPs during the 2010-2018 economic cycle.

This analysis [including other data points] allows us to “call” the end of drivable sub-urban sprawl in office, retail, and rental multi-family in the Boston metro area.

I’d say the jury’s still out—nothing ever really “ends.” And of course, the suburbs aren’t actually going anywhere, though they may (read: will) transform as our economy and our regulations do.

What is clear, though, from this study and prior ones, is that the fiscal case for walkability is strong—and so is the case that we don’t allow walkable development patterns in nearly enough places, including suburbs and central cities alike. Let’s fix that.

(Cover photo by Daniel Herriges)