"Does God care how wide a road is?"

Yesterday, in part one of this series, I wrote about how my wife, Kate, and I got serious about cultivating community among our actual neighbors—first in Portland, Oregon and then in Silverton, the small town 45 miles south of Portland where we live now.

Our community-building efforts focused on developing and deepening relationships, and enfolding hurting and lonely people into relational networks of care. This is rewarding work, and we were fortunate to develop life-changing—and lifelong—friendships in both places. Yet it was only after we moved to Silverton that we began to understand how aspects of the economy and built environment can undermine deep community. For a long time, we couldn’t fully articulate what was wrong, let alone a coherent approach to change.

That’s where Strong Towns came in.

Eric O. Jacobsen. Image via the Embedded Church podcast.

The first mention of Strong Towns in my email inbox is from December 2014.

Chris Smith, with whom I co-authored the book Slow Church, emailed me and two of our friends a link to a blog post Chuck Marohn had written. “Are you all familiar with the Strong Towns blog?” Chris asked. “Great post there today that fits with both New Parish and Slow Church.”

As it happened, I had started following Strong Towns just three months earlier, since listening to an interview with Eric O. Jacobsen on the Strong Towns podcast. Jacobsen is a pastor, author, urbanist, and the co-host of Embedded Church, a podcast that shares stories of churches in walkable neighborhoods. He also wrote two books that literally changed how I see my world: Sidewalks in the Kingdom: New Urbanism and the Christian Faith (2003) and The Space Between: A Christian Engagement with the Built Environment (2012).

I’m a Christian of Quaker persuasion. I really do try to let my faith inform every aspect of my life. Yet somehow it wasn’t until I read Sidewalks in the Kingdom that it occurred to me that I could—and even must—think “theologically” about how we build our towns and cities.

The more I read, the more I talked with Kate and our friends, the more attention I paid to where people were struggling in my own town, and the more I learned about “new urbanism”—a phrase I’m certain I’d never heard before Jacobsen’s Sidewalks—the more I started asking myself previously unimaginable questions:

Does God care how wide our roads are?

Does God have a preference for how tight the turning radius is at this intersection?

Will converting our downtown from one-way streets to two-way streets get us closer to God’s vision for shalom (peace)—or further away?

So, does God care how wide our roads are? I could only answer: Yes.

At the heart of my faith is the belief that we are created for community. And since the way we build and grow our cities can either bring people together or keep them apart, support human flourishing or work at cross-purposes to it, promote good stewardship of the land and its creatures or speed their destruction, I had to assume God had preferences. Preferences about the big things—like not running an interstate through a city and obliterating a neighborhood—and about the previously obscure details of my town, like whether an intersection turning radius should prioritize vehicle speed or pedestrian safety.

This is a ton of God-talk, and I promised my Strong Towns colleagues I wouldn’t be writing a theological treatise today. But the point of this series—and something we’re reminded of every Member Week, when our staff gets to connect with hundreds of our supporters—is that the Strong Towns conversation is one with many entry points. There are thousands of Strong Towns advocates standing together, all across North America (see the map below) and from nearly every walk of life. There are engineers and planners, architects and developers, mayors and city councillors, passionate community advocates (both professionals and laypeople alike), and more. We all have different Strong Towns origin stories, but we come together here (sometimes across major cultural and ideological divides) because we want our communities to be stronger, more livable, and more financially resilient...both now and long into the future. My Strong Towns journey happens to have begun as a faith journey.

After reading Sidewalks in the Kingdom, I followed Eric Jacobsen as best I could online. It was via Jacobsen that I stumbled across an organization called the Parish Collective, a network of faith communities across the world who are weaving fabrics of care in their particular neighborhoods. My wife and I have been involved with the Parish Collective since 2011 (Kate is now the board chair). Through Slow Church and the Parish Collective, we’ve met kindred spirits from around the world—including other people who were trying to think theologically about the built environment, and act faithfully in response.

We met a pastor in Seattle who, in order to best serve neighbors in danger of being displaced by gentrification, became a homegrown expert in zoning codes.

We met artists using their talents to beautify their neighborhoods, do intersection repairs, celebrate what is wonderful in their communities, and grieve what is broken.

We met a man who is caring for refugees who fled violence at home only to find themselves isolated and lonely after a few months in the U.S.

We met good people settling in for the long-haul to work for the flourishing of remote rural communities, inner-city neighborhoods, suburbs, trailer parks, and apartment complexes.

We connected with churches who are renovating abandoned and foreclosed houses on behalf of neighbors, creating community gardens, building Little Free Libraries, putting in bike lanes, helping neighbors start new businesses, and on and on.

All around the United States and Canada were these amazing people pushing back against something in their cities I can only describe as “anti-human.” Not always willfully anti-human, but anti-human nevertheless. But what was it we were pushing against?

This was the last big question for me. It wasn’t just happenstance that our roads were so unsafe that regular folk had to take matters into their own hands to slow the cars. It wasn’t by accident that many of our poorer neighborhoods were suffering from decades of disinvestment and deferred maintenance. It wasn’t a coincidence that every city seemed to have huge swaths of “non-places”—whether in the form of huge, mostly-empty parking lots, or mile after mile of chain restaurants, car lots, malls and big box stores.

We were all fighting the good fight, but I wasn’t sure who our real opponent was.

Then, in 2014, I listened to that interview on the Strong Towns podcast. After that, I started following Strong Towns in earnest.

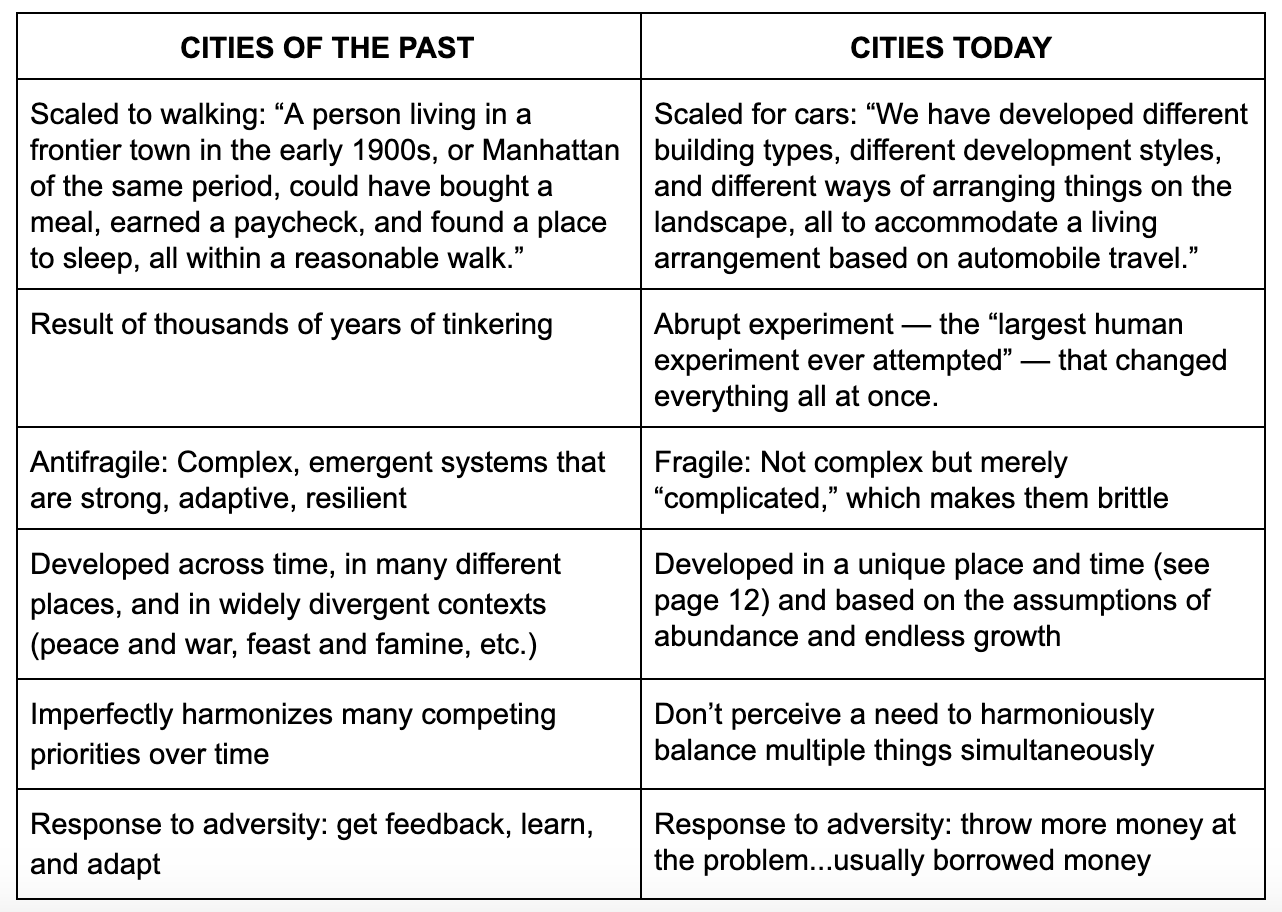

My friend Dwight Friesen, one of the co-founders of the Parish Collective, is fond of phoropter metaphors. A phoropter is the instrument used by optometrists to determine your eye prescription. (“Which is clearer: #1 or #2, #1 or #2?”) With Strong Towns, a lens clicked into place and the world around me became suddenly, stunningly clearer. (“#2!”) I began to see that what we were up against was a suburban development pattern that had been standard operating procedure since at least World War II. In both its speed and scope, it represented a radical break from how cities have been built for thousands of years. This chart, which I summarized from Chapter One of the Strong Towns book, begins to demonstrate just what a divergence it’s been:

Before Strong Towns it never registered with me that my kids and grandkids were going to have pay forever for all the new infrastructure we were creating. That we were going to need new growth to pay for the old growth—a kind of pyramid scheme that leads to decline and eventual collapse—was, I promise, something I’d never thought about either. But now I could see it all around me.

It wasn’t just Strong Towns’ diagnosis of the problems that resonated with me, but its approach to solving them too. Strong Towns took the long-view, resisted one-size-fits-all formulas, valued resilience over efficiency, and shifted the power for change from the top-down to the bottom-up. It was also hyperlocal, improving our cities neighborhood by neighborhood and block by block. In fact, what I now know as Strong Towns’ four steps of public investment sounded a lot like what our friends in the Parish Collective were already doing.

For years, the built environment was little more than a backdrop against which which my community building efforts were set. Only the most egregious cases of injustice—gentrification, redlining, and so on—caught my attention. Now I understood that our cities’ development patterns weren’t just the backdrop but rather the stage itself—a stage that influences what is and isn’t possible for the actors, one that the following generations will inherit, and one that we ultimately have control over.

I recently went back and re-read the post my Slow Church coauthor emailed me and our two friends. In “Living in Communion,” Chuck is reflecting on some anti-bike lane statements his priest made in church one Sunday. Chuck ends his post this way:

I’ve long wondered just how much more fulfilling our lives would be if we did not live in such isolation. If God dwells in each of our hearts—and I truly believe that is the case—then seeking to live in communion with God should mean that we seek to have lives immersed with each other. To truly live in this way cannot be an active pursuit, one in which we have to get in the car and drive 25 minutes to a parking lot at a set time for a scheduled event with a self-selected group of people. It must be passive, where our natural day-to-day existence includes random interactions with the humanity that makes up our community, be they Christian or not. Be they affluent enough to own a car or not.

Not only should we not be opposing bike lanes, church leaders around the country should be doing everything they can to reconnect the social bonds of our communities. We reconnect the social bonds most easily and effectively by reconnecting the physical bonds. We should not only be building bike lanes, we should be obsessed with getting people out of their cars and back into each other’s lives.

That’s a Strong Towns thing to do. I humbly suggest that it is also a Christian thing to do.

Five-plus years after first reading those words, I agree more than ever.

Other articles in this series:

Part One: We’re Not in Mayberry Anymore. And That’s a Good Thing.

Part Two: “Does God care how wide a road is?”

Part Three: I work for Strong Towns and sometimes even I know don’t know what the Strong Towns approach is.

Part Four: Finding the Good Life on Danger Hill

This is Member Week at Strong Towns. As we’ve seen, the Strong Towns conversation is one with many entry points. Will you help us reach even more people and grow this movement? Consider becoming a member today.

John Pattison is the Community Builder for Strong Towns. In this role, he works with advocates in hundreds of communities as they start and lead local Strong Towns groups called Local Conversations. John is the author of two books, most recently Slow Church (IVP), which takes inspiration from Slow Food and the other Slow movements to help faith communities reimagine how they live life together in the neighborhood. He also co-hosts The Membership, a podcast inspired by the life and work of Wendell Berry, the Kentucky farmer, writer, and activist. John and his family live in Silverton, Oregon. You can connect with him on Twitter at @johnepattison.

Want to start a Local Conversation, or implement the Strong Towns approach in your community? Email John.