Is Kansas City Still Living on Its Streetcar-Era Inheritance?

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a long-term series exploring the history of Kansas City and the financial ramifications of its development pattern. It is based on a detailed survey of fiscal geography—its sources of tax revenue and its major expenses, its street network and its historical development patterns—conducted by geoanalytics firm Urban3. Here are all the articles in the series:

Kansas City's Fateful Suburban Experiment • Is Kansas City Still Living on Its Streetcar-Era Inheritance? • "Kansas City's Blitz": How Freeway-Building Blew Up Urban Wealth • The Road to Insolvency is Long • Asphalt City: How Parking Ate an American Metropolis •

The Local Case for Reparations • Ready, Fire Aim: Tax Incentives in Kansas City (Part 1) •

The Opportunity Cost of Tax Incentives in Kansas City (Part 2) • The Numbers Don’t Lie •

Kansas City Has Everything It Needs

Streetcar on Grand Avenue in 1903. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Every city in history has been shaped by the prevailing transportation system of its day. Kansas City, Missouri and its adjacent namesake of Kansas City, Kansas are no different: during their heyday in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, their growth beyond the core downtown districts was largely dictated by the new technology of the streetcar. In fact, Kansas City once had one of the most extensive streetcar systems in the world. You wouldn't know it today: the last line was shut down in 1957, as buses replaced streetcars and core Kansas City neighborhoods experienced population decline while the suburbs boomed.

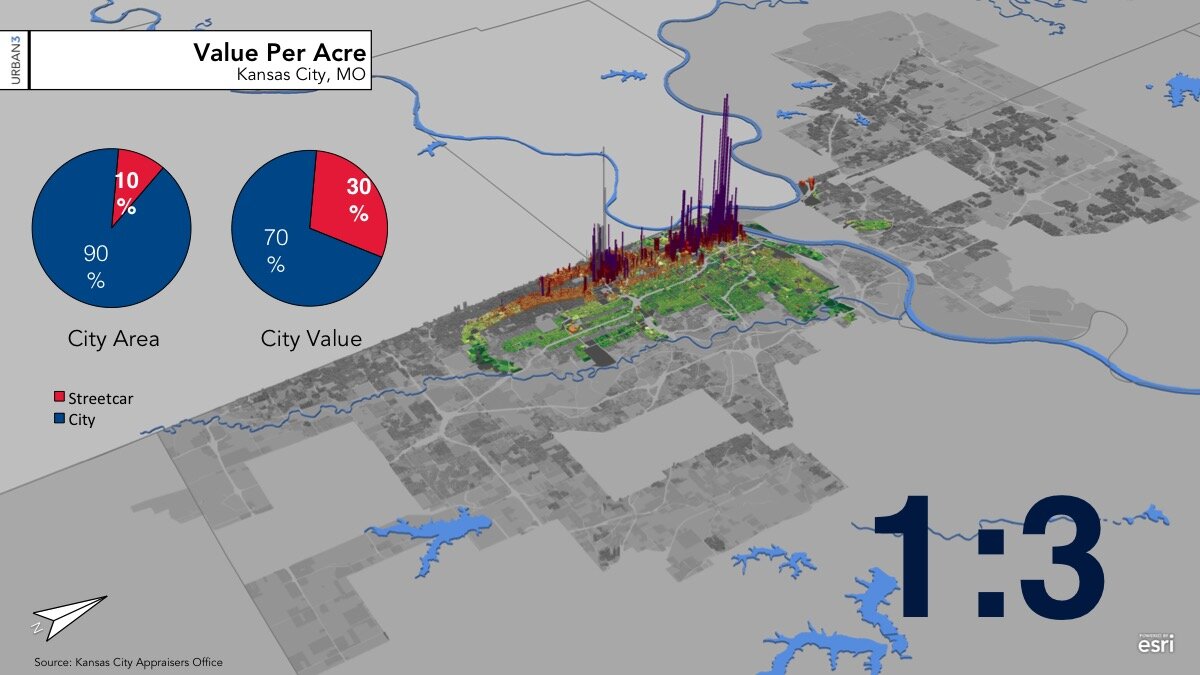

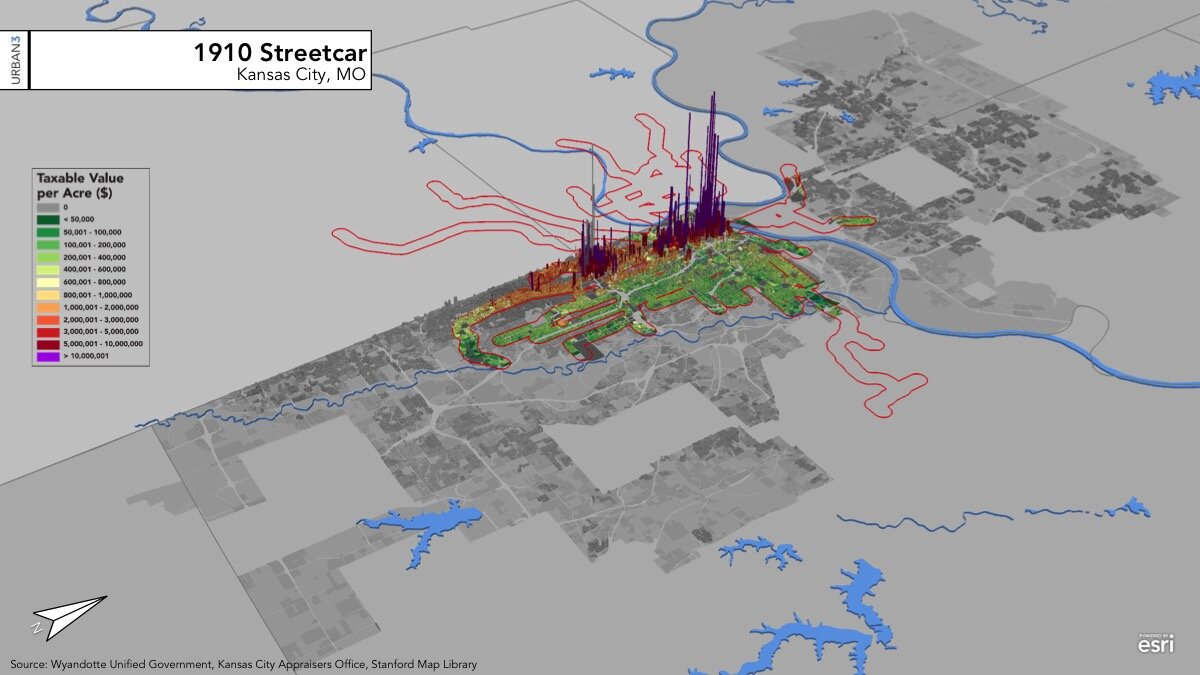

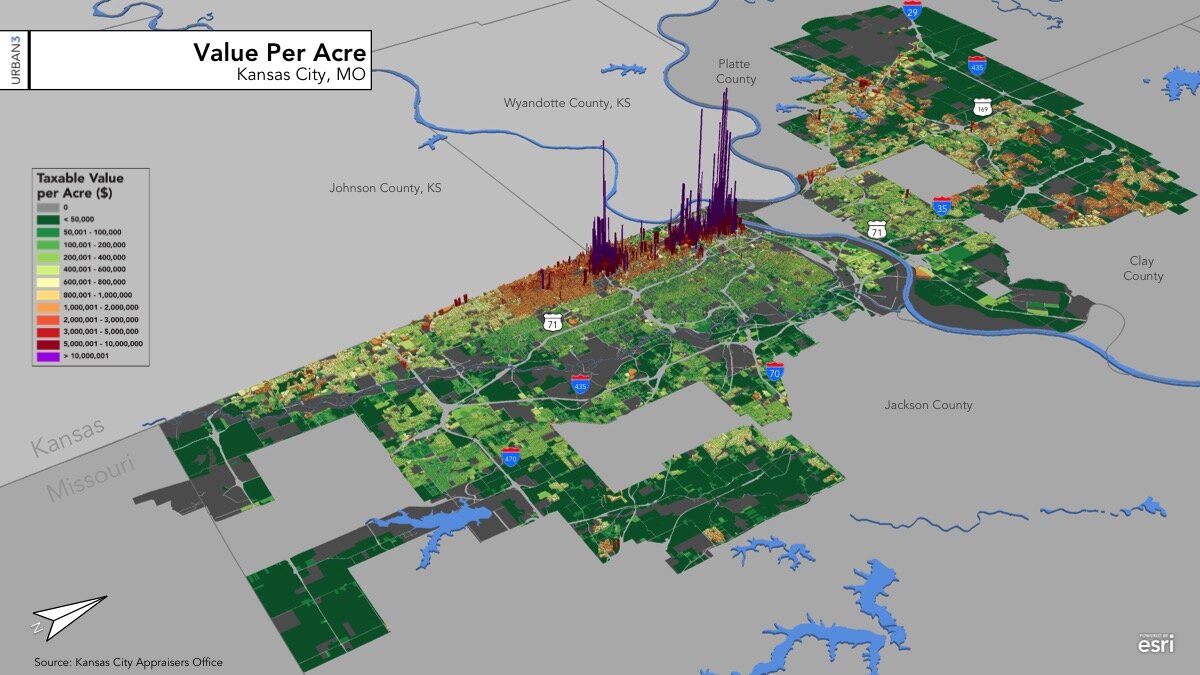

When we take a look at the value of the taxable property in Kansas City today—thanks to a thorough study conducted by geoanalytics firm Urban3—we see that the streetcar era left the city with an enduring inheritance. The pattern of development that streetcars fostered was a highly productive one that has stood the test of time. So well, in fact, that the places that were served by streetcars (within short walking distance of a line) in 1910 still provide an outsized share of the city's wealth in 2020.

The below slideshow shows the extent of 1910 streetcar lines, and reveals that the 10% of present-day Kansas City that was served by streetcars 110 years ago contains a full 30% of the city's property tax value today:

The Virtuous Cycle of Transportation and Land Development

This history provides a useful opportunity to reflect on the purpose of an urban transportation system. Done right, transportation goes hand in hand with building a productive place in a virtuous cycle. A productive place—as big as a neighborhood or city, as small as a single intersection—is one that people gravitate to, businesses invest in, and that thus generates the sustained wealth to ensure its own upkeep.

When we build transportation to connect such successful places to each other, the transportation investment, in turn, should increase the desirability of the place and the value of the land, encouraging further development. In fact, in many countries (Japan is a prominent example), that property development is used to fund the transit investment itself: an approach known as value capture that further contributes to the virtuous cycle. This is rarely true of U.S. public transit today; however, private streetcar operators a century ago often had close ties to real-estate developers—or were the developers themselves—and used exactly this model.

A cluster of older buildings in a traditional, mixed-use style. This kind of “node,” surrounded by less intensive development, is common evidence of where streetcar lines used to meet. (Image via Google Maps)

People aren't generally willing to spend more than about an hour of their normal day traveling from place to place—a rule known as Marchetti's Constant. As Kansas City boomed after the Civil War, it was streetcars—the first of which were actually horse-powered—that allowed the city to expand beyond the walking radius of its core downtown. Many of the neighborhoods that arose became enduring stores of wealth, tightly connected to the city by the tether of the streetcar line. The permanence of the stations encouraged investment: you can still see the legacy of many of these streetcar stations today, in concentrations of neighborhood-serving retail and mixed-use buildings.

And the walkability of a streetcar node meant that you could replicate a development pattern built to the human scale even outside of downtown. Kansas City developed a veritable alphabet of Missing Middle buildings: small apartments, fourplexes, neighborhood retail buildings, and so forth. Most would be illegal today because they don't provide any parking. They didn't have to in the 1920s: people lived off the streetcar, which connected areas on both sides of the state line, and served rich and poor, white and black neighborhoods alike.

Reviving a Good Idea?

Kansas City has a streetcar again. The modern incarnation (whose unofficial theme song by Kemet the Phantom you can hear on each week’s episode of our Upzoned podcast) opened in 2016, and serves a single 2.2-mile route between the River Market and Union Station, running through downtown. It has been one of the more successful modern streetcar projects, amid a host of high-profile, expensive failures in other cities (such as St. Louis and Atlanta) that don’t seem to recognize the fundamental purpose of transit.

Looking at a value per acre map helps reveal what the modern KC Streetcar does right: in a nutshell, it connects two productive places to each other. Two of the most productive places in the entire city, in fact. The KC Streetcar connects places where people have already demonstrated that they want to be, and knits those places closer together by making it easier to make short trips—say, between an office downtown and a bar in the Crossroads, or between a hotel near historic Union Station and a concert or sporting event at Sprint Center.

This does not mean that a streetcar is always the right solution to a 21st-century transportation problem. But it’s worth understanding what this means of connecting neighborhoods does best, when it works, and the advantages it bestowed in a prior era.

Put simply, if you live in Kansas City today, your great-grandparents’ generation invested in something that is still providing the foundation for much of the city’s wealth today. Consider it a civic inheritance.

In Contrast: The Freeway Model

The freeways built in Kansas City after World War II created very different incentives. Their primary function was to connect downtown to the growing suburbs; in the process, freeways acted as moats carving up and separating portions of the city, and proved disastrous for the value of centrally-located neighborhoods. In the next essay in this series, we’ll dig into Kansas City’s history with freeways, and how, rather than creating enduring value the way the streetcar system did, the freeways have destroyed such value.

Daniel Herriges has been a regular contributor to Strong Towns since 2015 and is a founding member of the Strong Towns movement. He is the co-author of Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis, with Charles Marohn. Daniel now works as the Policy Director at the Parking Reform Network, an organization which seeks to accelerate the reform of harmful parking policies by educating the public about these policies and serving as a connecting hub for advocates and policy makers. Daniel’s work reflects a lifelong fascination with cities and how they work. When he’s not perusing maps (for work or pleasure), he can be found exploring out-of-the-way neighborhoods on foot or bicycle. Daniel has lived in Northern California and Southwest Florida, and he now resides back in his hometown of St. Paul, Minnesota, along with his wife and two children. Daniel has a Masters in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Minnesota.