In Praise of Streetcar Suburbs

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared on the author’s blog, The Corner Side Yard. It is republished here with permission.

The Streetcar Suburb: What It Is, and What It Isn’t

Oak Park, Illinois. Image credit: David WIlson on Flickr

If there is a single American development pattern or style I love most, it is the streetcar suburb. Bringing more of this pattern back to our cities would be a great thing.

Let me address one misnomer at the outset. This development pattern is called streetcar suburb, but it's not always suburban in the way we understand post-World War II suburbia. In fact, it's largely only suburban (as in, an independent municipality outside of a central city) in some East Coast and Midwest cities. There, places like Somerville, Massachusetts, outside Boston; Philadelphia's Main Line suburbs; Shaker Heights, Ohio outside of Cleveland; and Oak Park, Illinois outside of Chicago (seen right) are streetcar suburbs in the purest sense. They did indeed develop as suburban areas outside of cities, yet connected to them via streetcar networks. In other areas of the country, however, streetcar suburb development became the de facto urban development pattern of some cities; they are firmly within the boundaries of central cities in other parts of the Midwest, and more often in the South and West.

So what are streetcar suburbs? They were the predominant development type within American cities from about 1890-1930. It was the most widespread development type prior to the Supreme Court's upholding of Euclidean zoning (Euclid v. Amber Realty) in 1926, which allowed municipalities to pursue greater separation of land uses.

The website Living Places documents well the rise and expansion of the streetcar suburb:

The introduction of the first electric-powered streetcar system in Richmond, Virginia, in 1887 by Frank J. Sprague ushered in a new period of suburbanization. The electric streetcar, or trolley, allowed people to travel in 10 minutes as far they could walk in 30 minutes. It was quickly adopted in cities from Boston to Los Angeles. By 1902, 22,000 miles of streetcar tracks served American cities; from 1890 to 1907, this distance increased from 5,783 to 34,404 miles.

By 1890, streetcar lines began to foster a tremendous expansion of suburban growth in cities of all sizes. In older cities, electric streetcars quickly replaced horse-drawn cars, making it possible to extend transportation lines outward and greatly expanding the availability of land for residential development. Growth occurred first in outlying rural villages that were now interconnected by streetcar lines, and, second, along the new residential corridors created along the streetcar routes.

Living Places elaborates on the development type, describing its characteristics:

Neighborhood oriented commercial facilities, such as grocery stores, bakeries, and drugstores, clustered at the intersections of streetcar lines or along the more heavily traveled routes. Multiple story apartment houses also appeared at these locations, designed either to front directly on the street or to form a u-shaped enclosure around a recessed entrance court and garden.

Why the Streetcar Suburb Should Make a Comeback

Personally, I love streetcar suburbs because they often have a mixed-use character that places built after them lack. There's also often a community or neighborhood connectivity within them that I find appealing; many streetcar suburb communities are full of proud, organized and vocal residents who advocate strongly on behalf of their community's values. But I find three reasons that highlight why the streetcar suburb was—and is—a superior development type, and why it will make a comeback as American suburbs mature.

1. They are adaptable. Streetcar suburbs were often built along grid networks, but not exclusively so; variations in block sizes and topographical adjustments can create differences in them. Streetcar suburbs were built and designed with streetcar systems in mind, but they generally have been able to succeed far longer than the streetcars themselves.

2. They are efficient. Streetcar suburbs can accommodate a broad range of residential types and sizes, from large-lot single-family homes to midrise and high-rise multifamily developments. This is largely due to the kind of street networks given to them by the initial streetcars that created them. Another key efficiency: streetcar suburbs are well-suited to the "missing middle" of multifamily residential development—the townhouses, duplexes and small (2-12 units) multifamily buildings that create housing diversity and improve housing affordability.

Image source: Wikipedia

3. They are inherently multi-modal. As perhaps the original transit oriented development type, they are quite able to accommodate public transit; it's in their DNA. However, even if streetcar networks never come back, they usually have transit supportive densities that make other modes, like buses or bikes, quite useful.

As today's suburbs are confronting ways to retrofit their development in the face of a changing economy and shifts in societal preferences, streetcar suburbs might offer some insight on how more recently built suburbs can make changes while maintaining their traditional appeal. My guess is that newer suburbs will look to implement many of the principles that girded the streetcar suburb.

But first, let me clarify a couple of things. My preference for the streetcar suburb is rooted in its land use design, and should not be taken as a public transit call to arms. I like public transit, make frequent use of public transit, and believe public transit should play a big role in the development of metropolitan areas. But some comments I've received thus far assume that I'm advocating for bringing back the streetcar as well as the land use design, and that's not necessarily the case. In fact, what I like about the design is that it is still fully functional long after the streetcar line tracks have been pulled up. Places like Birmingham, Michigan, outside of Detroit, do well despite losing the streetcar long ago. Some may argue that economics has more to do with that than land use design, but I maintain design is a significant factor.

The Benefits of the Streetcar Suburb, Illustrated

The adaptability and efficiency of streetcar suburbs is evident when illustrated. Below are some streetcar suburb design examples I've put together to illustrate the design's adaptability and efficiency. The examples assume a pretty strict grid orientation, but such a grid orientation is not necessary. Following the illustrations are land use data tables that provide a sense of the kinds of residential densities that can be achieved without the construction of a total high-rise environment.

As you look at the designs and the data tables, remember that there are essentially three principles that inform the designs:

Concentrate commercial development at the intersections of arterial roadways. In this instance, I'm assuming the roads at the edges of the designs to be arterial roadways that carry larger amounts of traffic.

Include mixed uses and multifamily uses along the interior parts of arterial roadways, and on collector streets. One problem with today's suburban development is the overabundance of commercial land as suburban municipalities try to game each other for commercial sales tax and property tax revenue. Most communities can't support the commercial development they try to attract; mixed uses and multifamily uses can be a more feasible option.

Keep single-family uses within the center of design sections, buffered from the edges by more intense uses. I know part of the appeal of single-family homes is the sense of separation from undesirable uses like multifamily or commercial uses. However, I think most people attracted to single-family homes will live with those uses as long as they are not immediately next to them, and will abide by more intense uses as long as their refuge area is maintained. This design scheme allows for that.

On to the designs.

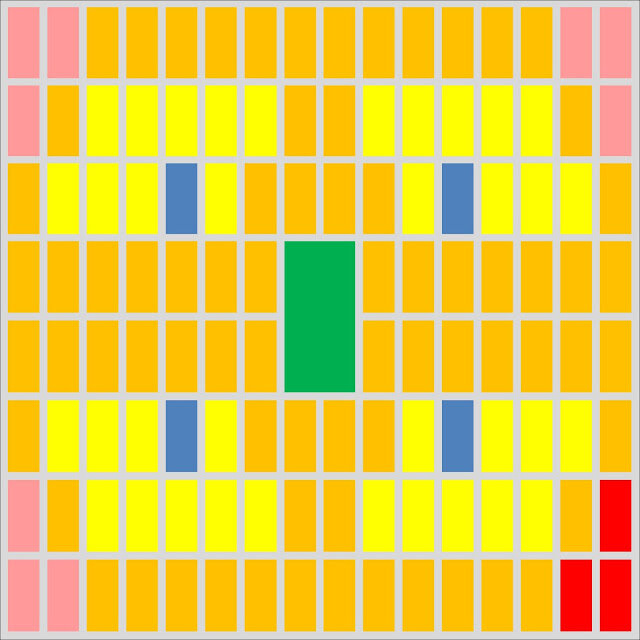

This graphic represents a low density streetcar suburb design for a one-square-mile area. For those unfamiliar with traditional "land use colors":

Yellow: Single-family home blocks

Pink: Mixed-use development blocks

Green: Parks/green space

Blue: Public/institutional uses (schools, churches, etc.)

Gray: Roadways

Subsequent graphics will include two additional land use types not shown here—orange (multifamily uses) and red (commercial uses).

And here's the data table that goes with it:

Assuming roads with a 66’ right-of-way for streets, a 66' x 124' typical single-family lot and even a 16 ' public alley between blocks, the design is able to achieve a pretty reasonable residential density of almost four units per acre despite the facts that more than three-quarters of the homes are single-family homes. On a net basis, the single-family homes come in at five units per acre, and the mixed-use areas at the corners of the design come in at 13 units per acre. Overall, assuming some reasonable household sizes, this design could accommodate more than 7,000 people per square mile.

Here's the medium density design:

And the medium density design data table:

Here, I removed some of the single-family blocks to include multifamily uses near commercial uses and mixed uses, and filling in multifamily uses on arterial roadways. Doing that shifts the proportion of unit types substantially (single-family homes now are 45 percent of all units, and multifamily and mixed-use units are 55 percent), but it does so without altering the character of the single-family blocks that remain. Single-family lots are slightly smaller (54' x 124'). Overall, the units per acre jumps to 6.7, and the gross density of the design jumps to more than 10,000 people per square mile.

Here is also a good place for me to elaborate on exactly the kind of multifamily development I envision in this design scheme. Notice that, in the data tables, I never call for more than four units per standard lot in any design scenario. That necessarily enforces a "missing middle" multifamily design of townhouses, duplexes, four-unit buildings and courtyard buildings that look much more like this—

—or this—

—and which can easily fit into the fabric of a community that has a strong single-family orientation without compromising its design integrity. Such multifamily designs can also stand on their own in larger multifamily sub-communities.

And now the high density design:

And the data:

Here, single-family lot widths are reduced to (an admittedly narrow) 33' x 124', and multifamily blocks line the arterial and collector roadways of the square mile site. Doing this causes the units per acre count to rise to nearly 13, and a gross density that exceeds 14,000 people per square mile.

Put it all together and what do you get?

Here I put together four square-mile designs (two low density and one each of the medium and high density) to see how it might look. I re-oriented the commercial and mixed uses in the medium density section (the upper right) to create a commercial core at the center of the larger area.

Here's the data:

Overall, you end up with a community that is efficient in its design, dense but not overwhelmingly so. This area could potentially house as many as 41,000 people in its mix of single-family and multifamily units, giving it a mix that is rarely achieved in most American cities and suburbs. As a four-square-mile area with nearly seven residential units per acre, it is able to be adequately served by public transit. The 40/60 single-family/multifamily unit split means that there should be units available in the area, making it affordable to a broader range of residents. The concentration of mixed uses and multifamily uses near the commercial center means there is a ready and sizable market nearby to support retail and services. Even as there are vibrant areas that would rely on pedestrian traffic, there are nearby single-family enclaves that can be refuges to those who want space, peace and quiet.

I understand the critiques that may come from people regarding these schemes. Those who know Chicago very well may see the city in these designs; I admit that. Others may say that the strong grid orientation isn't feasible everywhere, and that's true, too. Still others will say that the methodical implementation of the design is boring; I can't disagree with that, either, if it's implemented without ways to break up the grid in interesting ways.

Ultimately, as community retrofitting, particularly suburban retrofitting, starts to happen throughout the nation, communities should consider the three principles of the streetcar suburb mentioned at the outset: Create commercial centers, don't be afraid of mixed uses and multifamily uses, and set aside buffered single-family enclaves for those who want them. Do that, and we vastly improve the quality of our built environment.

About the Author

Pete Saunders is Detroit-born and raised, Hoosier-trained, and Chicago-polished. A planner for more than 20 years, he has worked in the private, public and nonprofit sectors, and is currently a planning consultant. He was steered into the profession by growing up in Detroit, and his interest has always been in the rise, fall and (hopeful) revitalization of old industrial cities. His writing has been featured in Urbanophile, Planetizen, Rust Wire, New Geography and the Atlantic Cities. He is also a regular contributor to Business Insider. You can connect with Pete on his website, The Corner Side Yard, and on Twitter @PeteSaunders3.

Varsha Gopal is an architect from Chennai, India. She joins Norm today to discuss discuss two research projects she recently conducted in her city and what they taught her about thriving cities, urban design and community engagement. (Transcript included.)