Ready, Fire, Aim: Tax Incentives in Kansas City

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a long-term series exploring the history of Kansas City and the financial ramifications of its development pattern. It is based on a detailed survey of fiscal geography—its sources of tax revenue and its major expenses, its street network and its historical development patterns—conducted by geoanalytics firm Urban3. Here are all the articles in the series:

Kansas City's Fateful Suburban Experiment • Is Kansas City Still Living on Its Streetcar-Era Inheritance? • "Kansas City's Blitz": How Freeway-Building Blew Up Urban Wealth • The Road to Insolvency is Long • Asphalt City: How Parking Ate an American Metropolis •

The Local Case for Reparations • Ready, Fire Aim: Tax Incentives in Kansas City (Part 1) •

The Opportunity Cost of Tax Incentives in Kansas City (Part 2) • The Numbers Don’t Lie •

Kansas City Has Everything It Needs

Country Club Plaza in Kansas City. Image source.

In the first few decades of mass automobile ownership, Kansas City, Missouri embarked on a ruinous development experiment, much like cities all over North America. After World War II, through aggressive annexation of outlying areas, Kansas City simultaneously spread its tax base thin and ballooned its infrastructure liabilities (as exemplified by an explosion of roads and parking). The building of inner-city freeways devastated neighborhoods and set off a wave of depopulation and vacancy. Kansas City steadily lost residents and jobs to its suburbs, and this wave was worst in areas that had already been crippled economically by a pervasive and racially biased pattern of mortgage redlining.

In recent years, Kansas City leaders have made concerted efforts to begin recovering the prosperity lost in that postwar era. Some of those efforts have helped, but others have only sunk the city deeper into financial quicksand. High on the latter list is Kansas City's prolific use of tax incentives for development.

Tax incentives are not strictly good or bad. They are a public policy tool. At their best they can tip the scale in favor of types of development that serve some public interest. Or they can jump-start positive change, in places where it’s badly needed, that the private sector doesn't have the momentum to deliver if left to its own devices.

But incentives have pitfalls. The use of them is a temptation that plays right into some very universal human shortcomings:

a bias toward excessive optimism when it comes to the plans and projects we want to see succeed;

a tendency to discount future risks—and tie the hands of future leaders—in favor of short-term gains;

magical thinking about how promised benefits are supposed to materialize.

Cities need to do the math, openly and rigorously, and use this tool with a clear and measurable idea of what they hope to achieve. Kansas City has often not met that standard. Though tax incentives are a powerful weapon to attack urban problems, Kansas City has a history of using this weapon recklessly and ineffectively: more “Ready, Fire, Aim” than “Ready, Aim, Fire.”

The Risky Allure of Tax Incentives

Since the 1980s, Kansas City has a history of aggressively using incentives—specifically tax increment financing (TIF)—to spur development. TIF is most often intended as a tool for local governments to redevelop blighted areas, where market-rate development would be unprofitable without assistance. Often there are high up-front infrastructure costs associated with urban redevelopment sites: things like demolition of old buildings, remediation of contaminated land, or upgrading water and sewer connections. TIF can help defray these costs where they would otherwise be a prohibitive barrier to any redevelopment.

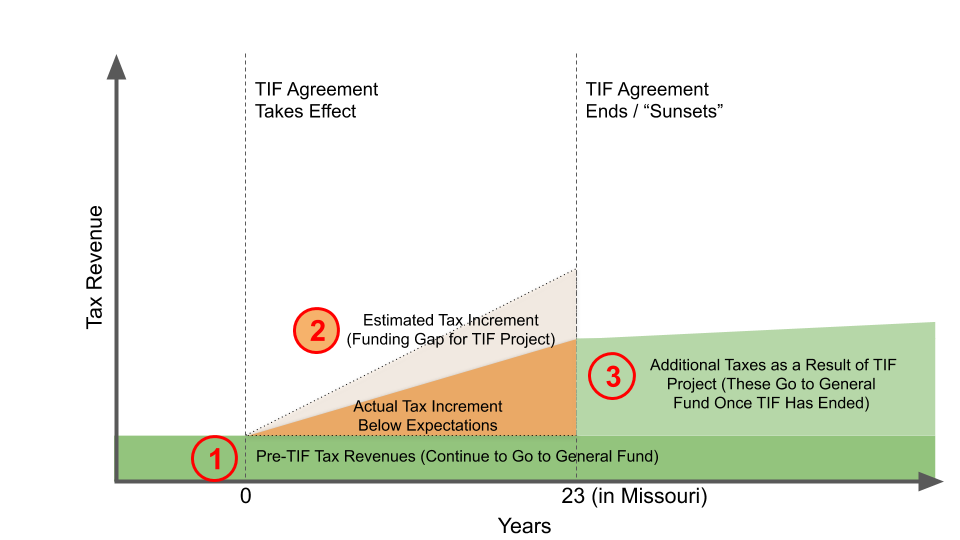

Under a TIF agreement, the local government designates a TIF district, which includes the specific property to be redeveloped but may also include nearby properties. Within the TIF district, property taxes are frozen at whatever their level was when the TIF was established. For a set period thereafter (in Missouri, up to 23 years) any taxes above and beyond that level—called the tax increment—go into a special fund used to subsidize specific costs associated with development of the property or associated public infrastructure. (The tax increment may also be simply forgiven and the property owner allowed to keep that money, in which case that is technically a tax abatement rather than a TIF. But don’t get hung up on the terminology.)

The appeal of TIF for local officials is that it is, in a sense, free money. Rather than a cash subsidy that must already be on hand somehow, the development is subsidized out of its own future taxes. The government, in theory, suffers no absolute loss of income: the tax increment consists of revenue that, but for the TIF, would never have existed at all, since development of the site would never have occurred. (We’ll revisit this “But For” test, an important part of the rationale for TIF, in Part 2 of this article.)

TIF may thus have the feel of a magic trick straight out of the Land of Oz. But it’s not: like any sort of debt, it’s simply a financial way of transferring resources from the future to the present. And, like any debt, it can be worth it, if we invest those resources in the present in a way that ends up making us richer in the future. That’s the fundamental test.

TIF can be a disastrous deal if the tax increment fails to materialize—which can happen because the developer misjudged the market, because the market changed rapidly, or because something else went wrong with the project. This can leave a shortfall in the project funding that must be filled, perhaps even out of taxpayer dollars depending on the specific terms of the agreement.

TIF can also be harmful if it is repeatedly used to subsidize, replace or crowd out development that would have happened anyway. In this case, tax revenue that the normal course of growth would have resulted in being available to the city is not available, because it has been siphoned away into a TIF district. That’s money that now isn’t available for schools, parks, public safety, public works—any of the normal business of running a city.

There are a lot of ways, in short, for a tax incentive deal to go wrong. And in Kansas City, the history of TIF has been characterized by a freewheeling approach to incentives that has not always produced strong returns, or reflected any clear and urgent public purpose.

Kansas City’s Troublesome Love Affair With TIF

This map shows the geographic extent of TIF districts in Kansas City, MO. TIF has been used as a tool in every section of the city, and in many areas that are neither poor nor disinvested. Click to view larger. (Source: Urban3)

TIF has shaped the face of modern Kansas City. Its most prominent use has been for the massive Power and Light District redevelopment, which we’ll discuss further in a future article. But TIF has been used as an all-purpose economic development tool across the city, from downtown to areas south to the largely-suburban-in-character Northland, and even previously undeveloped land (see the massive Shoal Creek Parkway TIF district on the accompanying map). It has been used for hotels; it has been used for office buildings; it has been used for historic preservation and for big-box retail; it has even been used to subsidize parking garages.

Given the broad range of sites and purposes to which Kansas City has put TIF, a noteworthy absence on the map is any TIF in most areas of the east side that were redlined and severely disinvested in for decades. A 2007 study found that at the time, 88% of TIF plans were in the four council districts (out of six) with the most affluent residents. The determining criterion for TIF in Kansas City does not appear to be the desire to turn around blighted neighborhoods, so much as economic development wherever the city can get it. (For what it’s worth, a city official told KCUR in 2016 that the issue on the east side was a lack of interested developers.)

This might be defensible if these projects were consistently generating positive economic returns, and thus revenue that could be put to any number of productive uses. But many of Kansas City’s TIF districts have floundered, and some have required multimillion-dollar bailouts at public expense. A third-party study by the libertarian Show-Me Institute found in 2017 no evidence that TIF had generated tangible net economic benefits in Kansas City.

Individual projects have sometimes borne fruit. An analysis by Urban3 of several specific TIF deals in Kansas City looks at a simple juxtaposition: how much subsidy did the project receive from TIF, and how much did the site’s value increase? A TIF that does not even recoup its own public investment in resulting property value is surely a money hole, and a project that should never have been subsidized.

Even if a TIF project does more than break even by this measure, there may be reasons it should not have received TIF—and this has a lot to do with the “but for” test. Again, more on this in the following article. For now let’s just say that even a seemingly in-the-black TIF deal might be more troublesome than meets the eye.

Urban3 has illustrated, in a series of graphics, a stunningly broad range of return on investment in just a few Kansas City TIF projects, from deeply negative to positive many times over—complete with promised magical Land of Oz metaphor to drive home the point that TIF is a tool that can be used for good, bad, or perhaps even wicked results. (The years in the top corner represent the period that each TIF will be in effect.)

There is an involved and nuanced story behind each of these projects which isn’t contained in the numbers you see here—and we will revisit a couple of them in the future. The point is that Kansas City has approved a startling range of these projects, in a startling range of contexts, without much evident scrutiny as to whether the assumptions about return on investment were accurate or reasonable.

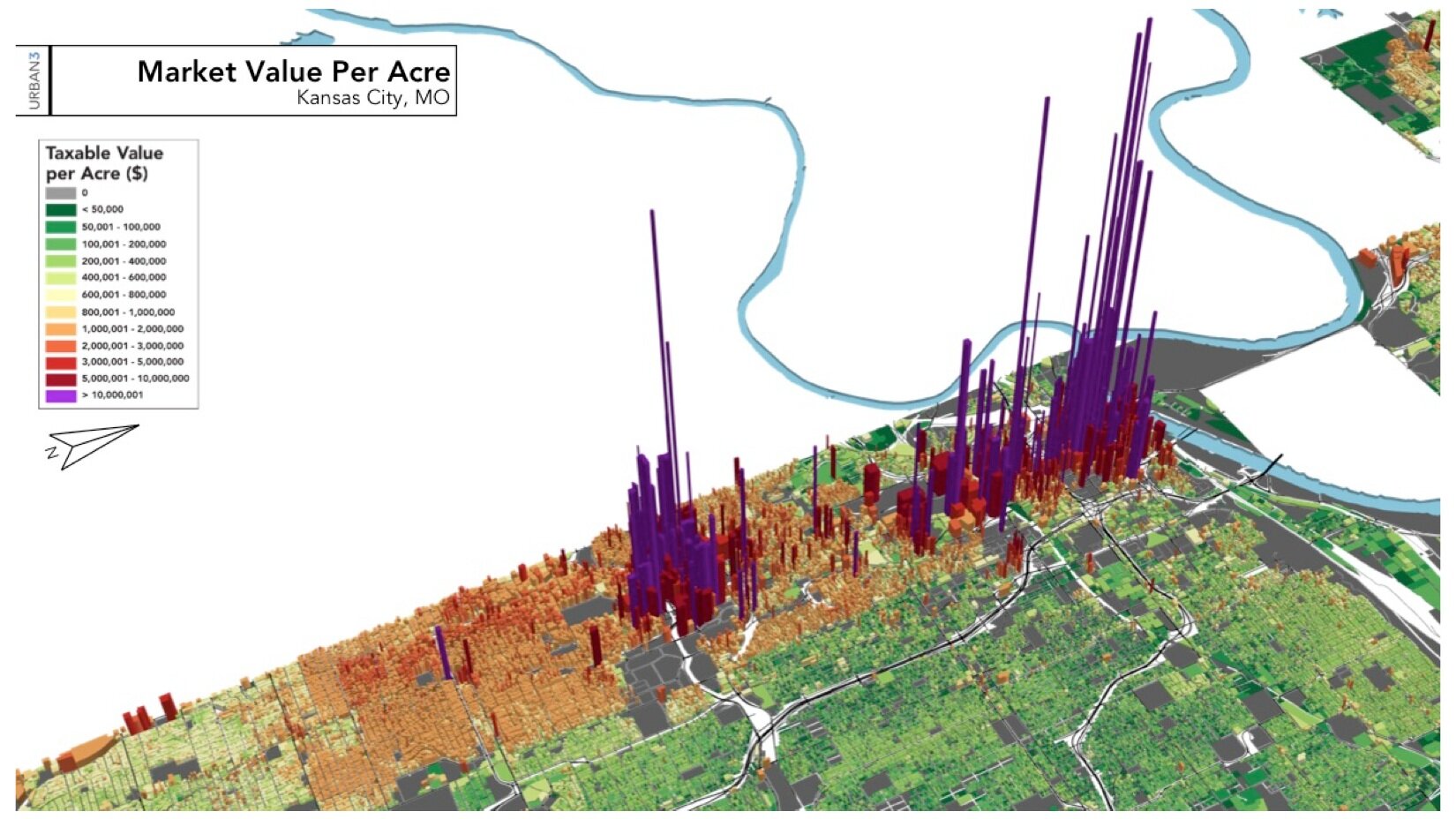

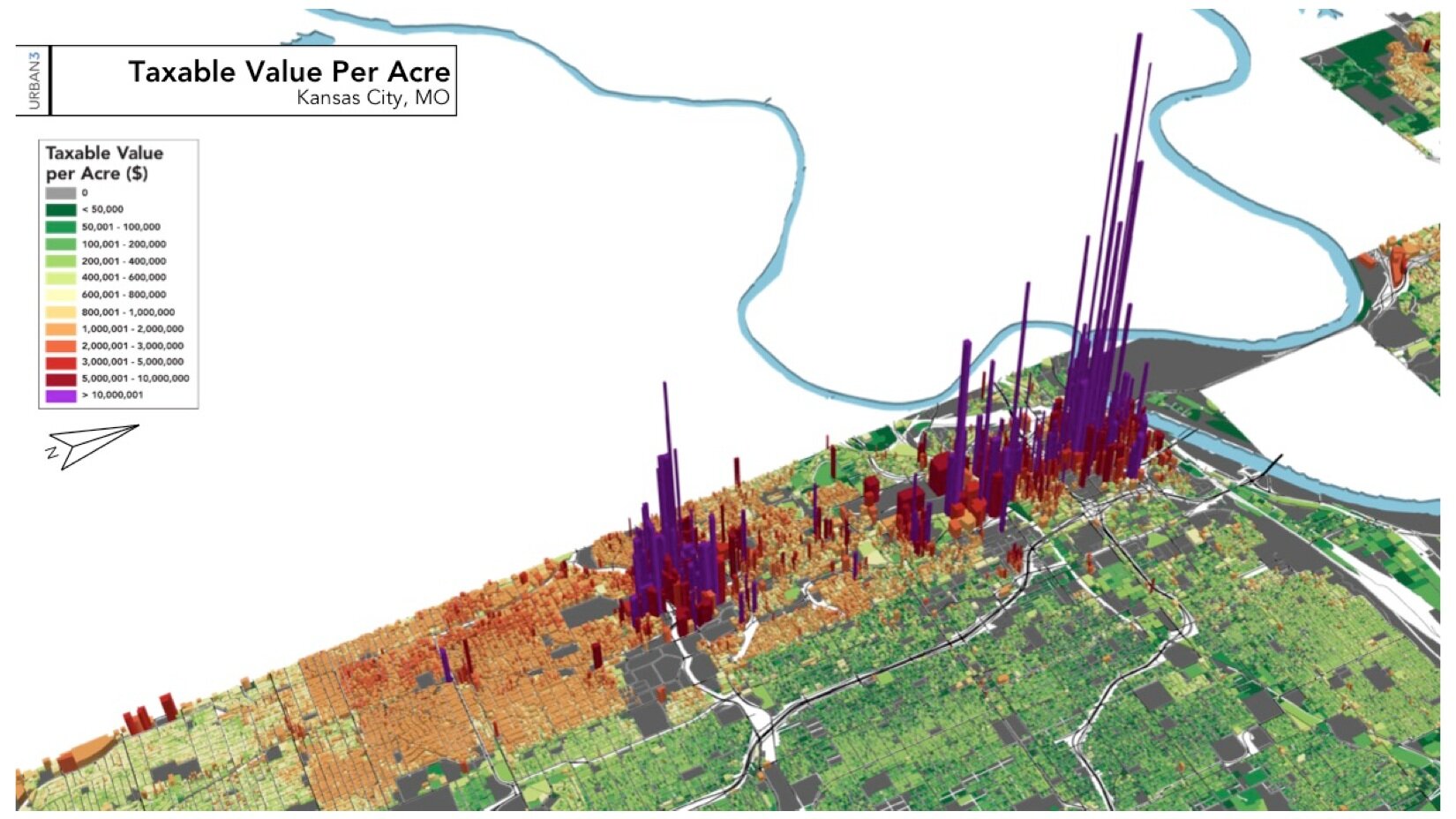

TIF removes much of the value of affected properties from the tax rolls which support all city services. The below pair of images illustrates the difference between the market value per acre of properties in Kansas City’s core neighborhoods, versus the taxable value per acre. In both cases, the height of a bar represents value per acre, and thus the volume of the bar represents the aggregate value (either actual or taxable) of that piece of property.

Watch many of the purple bars shrink from “market value” to “taxable value:” this is value that has been lost to tax reductions including TIF and abatement.

The incorporation of so much of Kansas City into TIF districts ties the hands of the next generation of leaders. It takes revenue out of bounds for them. And even if Kansas City didn’t ever approve another TIF district, it would take 20 more years for the existing ones to sunset (or “mature”) and for the taxes from those projects to return to the city’s general fund. In theory, the properties will be worth a lot at that point, and now their full value will be going to the general fund, rendering the TIF worth it. In practice, this is only sometimes the case.

This chart shows the amount of Kansas City’s land that will be in TIF districts, by year, assuming no new TIFs are established going forward and existing ones gradually expire. Source: Urban3.

Urban3's analysis of the city's fiscal geography helps us visualize the financial stakes for Kansas City as a whole, and also look at whether individual projects are delivering.

Ultimately, Kansas City needs to reckon with its development pattern: where most of the wealth that pays its bills is produced, and where the city is falling short of generating enough wealth to pay those bills. TIF is a dangerous tool for a city in a revenue squeeze, because it makes it possible to only delay or hide from that reckoning. It creates the temptation for local officials to prioritize “getting projects done”—with what feels an awful lot like a source of free money to kick-start them—over a more sober evaluation of which projects actually deserve to happen.

In part 2 we’ll look at the ways in which the “but for” test is not always good enough, and why we need a much more nuanced understanding of when TIF generates real value for the community, enough to outweigh the associated risks.

Daniel Herriges has been a regular contributor to Strong Towns since 2015 and is a founding member of the Strong Towns movement. He is the co-author of Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis, with Charles Marohn. Daniel now works as the Policy Director at the Parking Reform Network, an organization which seeks to accelerate the reform of harmful parking policies by educating the public about these policies and serving as a connecting hub for advocates and policy makers. Daniel’s work reflects a lifelong fascination with cities and how they work. When he’s not perusing maps (for work or pleasure), he can be found exploring out-of-the-way neighborhoods on foot or bicycle. Daniel has lived in Northern California and Southwest Florida, and he now resides back in his hometown of St. Paul, Minnesota, along with his wife and two children. Daniel has a Masters in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Minnesota.