4 Reality TV Lessons for Your Town

Erin and Ben Napier of Home Town Takeover. (Source: HGTV.)

Back in February 2020, I wrote an article about a new HGTV show that was inviting small towns to participate in a reality TV “takeover.” Prospective towns had to have a population of less than 40,000, as well as good bones: “great architecture longing to be revealed” and a main street that needed a “facelift.”

I had strong reservations about the concept, as I explained in my article: “The language of a ‘takeover’ clashes with the Strong Towns vision of a ‘bottom-up revolution’—neighbors from all walks of life working together to incrementally build strong, better-connected, and more financially resilient communities. Also, growing stronger communities is long, difficult work, the result of many decisions (large and small) over many years. I’m not going to say that work isn’t sexy, but…I’m also skeptical how well this work translates to the small screen.”

But I softened a bit. The new show, Home Town Takeover, was going to be a spinoff of an HGTV hit called Home Town. The hosts of both are Erin and Ben Napier. To get a sense of what the Napiers are all about, I watched the first season of Home Town. And I admit, I was charmed. Home Town isn’t a run-of-the-mill home renovation show. The Napiers are passionate advocates of their own rural community, Laurel, Mississippi. They are small business owners there. The homes they rehab are in Laurel’s walkable core. Often, the Napiers explicitly welcomed people not only to a new home but to a new hometown.

Strong Towns readers who were familiar with the steady transformation happening in Laurel also helped ease my concerns about the new show. “If they do what they did in Laurel, it is incremental, and preservation oriented,” one reader said. “I think it will be a good thing.”

Wetumpka, Alabama

I missed Home Town Takeover when it aired weekly earlier this year. Only recently did I go back and watch all eight episodes. It turns out that more than 5,000 small towns applied to be on the series. And from among those, one was chosen: Wetumpka, Alabama.

Wetumpka (population 7,220) is in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. A river, the Coosa River, runs through it. Less than half an hour from Montgomery, longtime Wetumpka residents say the town began to decline when the Highway 231 bypass was built and began ferrying people away from the downtown. (This is a story sadly familiar to many rural communities.) Then in January 2019, a powerful tornado hit Wetumpka. Thankfully no one was killed, but the storm destroyed or damaged churches, civic buildings, and homes, many of which were located right across the Coosa River from downtown.

With only four months to work in Wetumpka, the Napiers and HGTV focused on 12 projects that would have, in Erin Napier’s words, the biggest impact in the shortest amount of time. From there, said Ben, the town could “hit the ground running with their revitalization.”

The Napiers renovated the homes of several residents who are quietly making a difference in Wetumpka—foster parents, arts leaders, mentors, a beloved community police officer—as well as some iconic houses, including the house featured in the movie Big Fish. The Napiers also renovated small businesses downtown. They overhauled Wetumpka’s only event space. They built a farmer’s market on land that had been sitting vacant since the tornado. And they gave a makeover to an entire street of downtown storefronts.

4 Reality TV Lessons for Your Town

By the end of the first episode, I was already watching the show with a notebook on my lap; there were good lessons here. What I didn’t know then is that the final episode, “Talk of the Town,” lays out some strategies viewers can use to help revitalize their own towns. Many of the steps described there were ones I planned to highlight, too. Rather than spoil the ending—I really do think Strong Towns advocates will enjoy watching the show—I am going to highlight a few key takeaways.

Lesson #1: Small Towns Are Struggling

The first lesson of Home Town Takeover has to be that small towns across the United States are struggling. More than 5,000 communities tried to get the attention of the show. How many others are in trouble but didn’t apply?

Rural communities face a number of daunting challenges. Populations are stagnant or declining. Especially acute is the loss of young people who leave town for school or work and don’t come back. In many communities, as in Wetumpka, roads that used to channel people slowly through a town are now being diverted to move them quickly around it. Small towns that have been overly reliant on one industry or employer are especially vulnerable to economic shocks. (We published a whole series on this topic earlier this year.)

The temptation to kickstart growth now by mortgaging the future is real. An entire continent of small towns have traded the traditional development pattern, which helped make them prosperous and resilient, for a Suburban Experiment that squanders resources and makes communities fragile. And all that new growth on the outskirts of town? It may seem like a good idea now, but it can’t actually pay for itself. The long-term liabilities (the roads, the pipes, and other infrastructure) will be a millstone around the neck of your town’s finances…and small town budgets didn’t have much margin for error to begin with.

Lesson #2: Small Towns Are Beloved

Those 5,000 nominations represent tens of thousands of smaller communities that are struggling. But that’s only half the story. They also represent the tens of millions of people who live in, and love, their small American towns.

In Home Town Takeover, Wetumpkans talked movingly about their city. Yes, the community has its struggles, but it was clear how much residents loved Wetumpka. A phrase used several times in the show is “pride of place.” The importance of pride of place can’t be underestimated. As my colleague Daniel Herriges has written, the knowledge needed to successfully revitalize a place is deeply local, and the energy required must be a grassroots energy, from people with a “surplus of pride of place.”

Pride of place gives us the spark we need to take that first action to make our towns stronger, and it can keep us going for the long road ahead. It should also act as a filter we use to evaluate the decisions we daily make for our communities. Through huge tax breaks and other expensive giveaways, towns compete with one another to lure potential employers or the big box store. We’ve described this as a race to the bottom. More crudely, it is municipal prostitution and your town deserves better.

I was recently with Strong Towns president Chuck Marohn in a midwestern city where someone told us about a proposed project that might help attract new employers. The project itself—a series of bike trails—wasn’t necessarily a bad one, but the framing of it—attracting outside businesses—was askew. Rather than trying to be lovely for outsiders, Chuck said, we must first be lovely for ourselves. It’s a subtle but important difference, one that keeps us focused on making better the lives of people who live here now…and one rooted in pride of place. The paradox is that towns, like people, become more attractive to others when they become more attractive and confident to themselves.

Lesson #3: Start with What You Have

People who want to start revitalizing their towns often face a choice: (a) focus on what you have, and then build from there, or (b) fixate on what you lack, and probably stay stuck (or move backward) for a long time.

I’ve always been drawn to asset-based community development (ABCD), an approach to community building characterized by three key characteristics (described in detail here). ABCD is:

Asset-based: It starts with what is present in the community rather than what is absent.

Internally focused: Local definition, local investment, local creativity, local control, and local hope are of primary importance.

Relationship driven: ABCD requires constant building and rebuilding the relationships between and among local residents, local associations, and local institutions.

My wife and I have led asset-mapping workshops where we help groups identify different kinds of assets—physical, economic, relational, etc.—in their community. People take three to five minutes to write down, on separate slips of paper, all the assets they can think of in a particular category. Then we have them come up to the front and attach it to some butcher block paper we hung on the wall. Time after time, these accumulated assets cascade down the length of the wall and along the floor. It is a powerful visual reminder of the abundance that already exists in a community; it moves participants out of a scarcity mindset that can be so constrictive. The power of an asset-mapping workshop is similar to what Erin Napier said about Wetumpka, “We’re here to show them how special what they already have is.”

Except perhaps with the farmer’s market, the Home Town Takeover team didn’t focus on what Wetumpka was missing but on what was already there: natural assets like the Coosa River, great businesses, entrepreneurs and local leaders, local landmarks, and local history. They used a general contractor and senior tradesperson from Wetumpka. They enfolded local artisans—a quilting club, a woodworker, a glass restorer, an art class, and more—to help with projects.

“Small towns can’t afford to not celebrate every asset they have,” Ben Naper said multiple times, and there was a use-what-you-have mentality throughout the series. For example, to renovate a downtown barbershop they used wood from a church destroyed by the tornado.

The team also gave a makeover to Company Street downtown. Yes, the work they did on Company Street was mostly cosmetic but, with some paint and lights, a half-forgotten street suddenly looked loved and vibrant again. New businesses almost immediately started moving in, and now Company Street is at 98% occupancy.

Lesson #4: Start Right Now

Another project Home Town Takeover organized in Wetumpka was to paint the doors of all the houses on a residential street leading into downtown. From what I could tell, residents got into it. One resident said, “If everybody does one small, little thing—paint their front door, plant some flowers—that can just lead on and on until lots of little things are done and it’s now a big thing.” Another Wetumpkan said, “I think the project that we’ve done uplifts the community. It makes other people paint their houses. It makes the next door neighbor want to do something.”

There’s a kind of momentum that builds when we start taking incremental steps to make our towns stronger. One of the underlying problems many neighborhoods face—whether rural, urban or suburban—is a lack of confidence. Residents are hesitant to invest their money, time, energy and affection in a community that seems to be declining. But that can shift when even a very few people decide to show they care. This is the genius behind the work our friends at the Oswego Renaissance Association (ORA) are doing in Upstate New York. The ORA gives small matching grants to clusters of homeowners who want to collaboratively improve the exterior of their neighborhood. As I wrote last year, “This results in a huge return on investment, not to mention the value of neighbors working together...often for the first time. This is a simple but profound process that unlocks neighbors’ confidence in their neighborhood.”

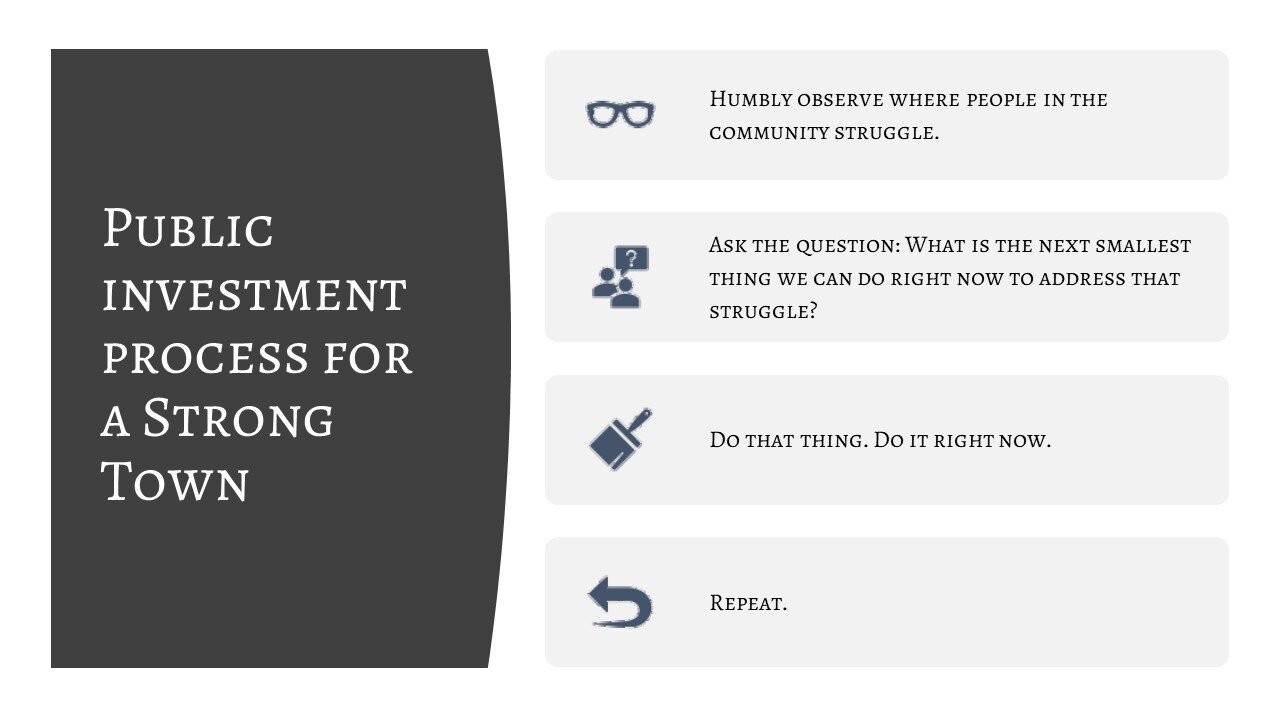

The same virtuous cycle is at the heart of the four-step Strong Towns approach to public investment:

Humbly observe where people in the community struggle.

Ask the question: What is the next smallest thing we can do right now to address that struggle?

Do that thing. Do it right now.

Repeat.

There’s a lot of work to be done in our small towns. So much that it’s easy to be overwhelmed by the scope of the challenges. But the way to set that virtuous cycle in motion is to start right now. As Ben Napier is fond of saying, “How do you eat a whale? One bite at a time.”

Is This the Start of a Small Town Movement?

Throughout Home Town Takeover, the show’s stars and producers are explicit about their larger goal: to start a movement. “HGTV is starting a small town revitalization movement,” Ben says. And later, he says the goal is to “start a movement of people creating change right where they live.”

At Strong Towns, we are trying to grow a movement, too—a movement dedicated to making communities across the United States and Canada financially strong and resilient. I’d go so far as to say, humbly, that there’s a lot of overlap between what Home Town Takeover was trying to do and what Strong Towns is doing.

There’s an important thing to remember, though: HGTV isn’t coming to save your city. In fact, it never was. Your town had a 1 in 5,000 chance to be picked for Season 1 and it looks like there isn’t going to be a Season 2. What’s more, the Napiers were clear that the best thing they could do for Wetumpka was to kickstart the process and then pass the baton to Wetumpkans themselves. Ultimately, it’s up to them.

And it’s up to you. So, sure, watch the show. It’s entertaining, inspiring, and even instructive. But then find a couple friends and start—right away—doing what you can to build your strong hometown.

John Pattison is the Community Builder for Strong Towns. In this role, he works with advocates in hundreds of communities as they start and lead local Strong Towns groups called Local Conversations. John is the author of two books, most recently Slow Church (IVP), which takes inspiration from Slow Food and the other Slow movements to help faith communities reimagine how they live life together in the neighborhood. He also co-hosts The Membership, a podcast inspired by the life and work of Wendell Berry, the Kentucky farmer, writer, and activist. John and his family live in Silverton, Oregon. You can connect with him on Twitter at @johnepattison.

Want to start a Local Conversation, or implement the Strong Towns approach in your community? Email John.