The Republican Roadmap on Infrastructure (It's Not a Real Plan)

Earlier this year, I wrote a 5-part series about the American Jobs Plan, the Biden administration’s proposal for infrastructure spending. It was something like 10,000 words (you can get a copy of the entire series in a pdf here) but for those of you uninterested in the deep nuances of how federal transportation and infrastructure spending harms local communities, I’ll summarize with this: When it comes to infrastructure, the American Jobs Plan is business as usual, simultaneously massive in the amount it spends, underwhelming in what it accomplishes, and wholly inadequate when it comes to meaningful reform. It will make America poorer.

In the partisan time we inhabit, it was difficult for some to read this critique without resorting to their own political priors. I get that, even though I find it tiresome. I’m not bipartisan or even nonpartisan—I’m just tired of it all and, quite frankly, bored with everything Washington D.C. I have friends and family members who live and breathe this stuff and that passion is perhaps the most uninteresting thing about them.

Bottom-up excites me. Local communities excite me. Great mayors, crazy local entrepreneurs, and concerned citizens out planting trees, painting crosswalks, and building community: that’s where my passion is.

Even so, I’ve been asked to, in the spirit of being even-handed, critique the Republican infrastructure plan with the same level of scrutiny and analysis I applied to the American Jobs Plan, as if these are somehow equivalently serious proposals. They are not.

I printed out the American Jobs Plan and it was 27 pages long. If submitted as a graduate school paper, a professor would rightly grade it poorly due to it being too wordy, repetitive, and formulaic. In contrast, the Republican Roadmap—the Republican’s alternative proposal—is two pages of superficial bullet points. It is so lacking in detail that it doesn't even indicate what time interval the spending proposals cover. Do they plan to spend $299 billion on roads and bridges next year or next week or over the next decade? Who knows?

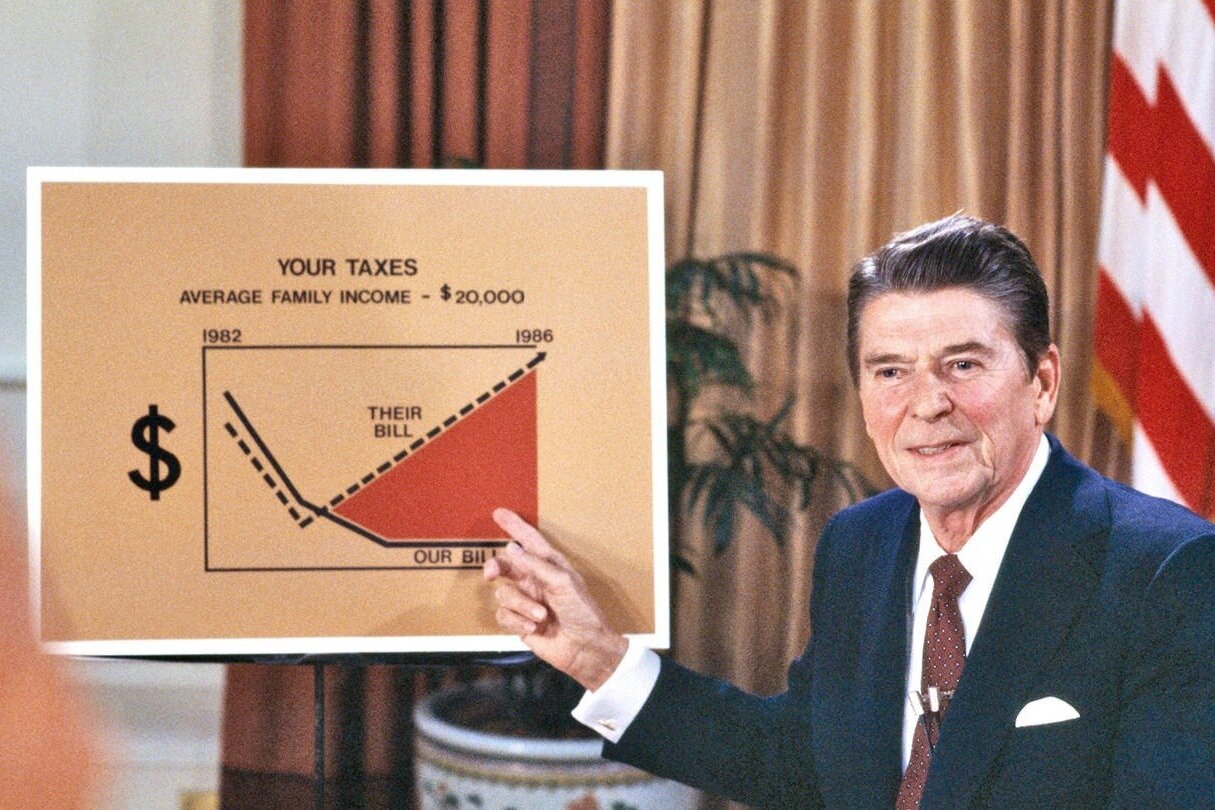

Who cares? After reading it and the dialogue around its rollout, I don’t think that Republicans do. These are just talking points meant to emphasize difference, not a serious proposal to enact a vision. The difference in approach here reminds me of these images (and, yes, I know one of these is real and the other a parody; that’s part of my point).

How do you analyze a non-plan? You don’t, and I’m not going to try. If there is an infrastructure bill approved this year, it will be the Biden plan with potentially some tweaking to accommodate Republican priorities and areas of consensus.

Unfortunately, the only real area of bipartisan consensus is the destructive belief that we need a lot more spending on roads and bridges. I’ve seen this chart from the National Association of Counties show up in a number of places. Note that the highest spending priority for the American Jobs Plan is roads and bridges. Also note that the highest spending priority for the Republican Roadmap is roads and bridges.

Obviously, any bipartisan consensus on infrastructure spending is going to start with lots of money for roads and bridges. As we at Strong Towns have said for many years: the last thing this country needs is more roads and bridges, yet it seems almost certain that we are going to get a lot more money for existing road and bridge programs—programs that continue to prioritize new projects and system expansion.

As I wrote recently for CNN, the interstate system is built. It’s done, and it’s time to move on. We need to get to work thickening up our cities, towns, and neighborhoods, allowing them to become more financially productive and prosperous. More road and bridge spending (the item of greatest bipartisan consensus) will undermine that work unless there is a serious commitment to reform existing programs.

(Note: There is no substantive discussion, let alone serious commitment, to reform existing road and bridge programs. Why would there be since both parties are enthusiastic to provide even greater amounts of funding for the current slate of programs?)

Someone recently shared with me an announcement from the city of Littleton, Colorado, regarding their severe revenue shortfall, and it demonstrates the impact when it comes to our bipartisan consensus on transportation funding. As they say on their website:

Littleton’s list of unfunded capital and infrastructure projects totals $98 million over the next 15 years. This is due in part to an underfunded street maintenance budget….

And then later:

...the Capital Projects Fund – which should pay for these projects – only brings in about $6 million each year, half of which is earmarked for street maintenance. And that $3.1 million for street maintenance only meets about 25 percent of the annual need.

The page goes on to present a misdiagnosis of their problem, pinning Littleton’s woes on rising costs and a lack of tax revenue as opposed to the reality: Littleton, like nearly every American city, has an unproductive development pattern and it is slowly bankrupting them, making them unable to sustain even their essential services.

Putting more federal money into programs that are making our cities poorer is only going to do harm. The debate on infrastructure spending right now between Democrats and Republicans in Washington D.C. is over just how much harm: an enormous amount or a catastrophic amount.

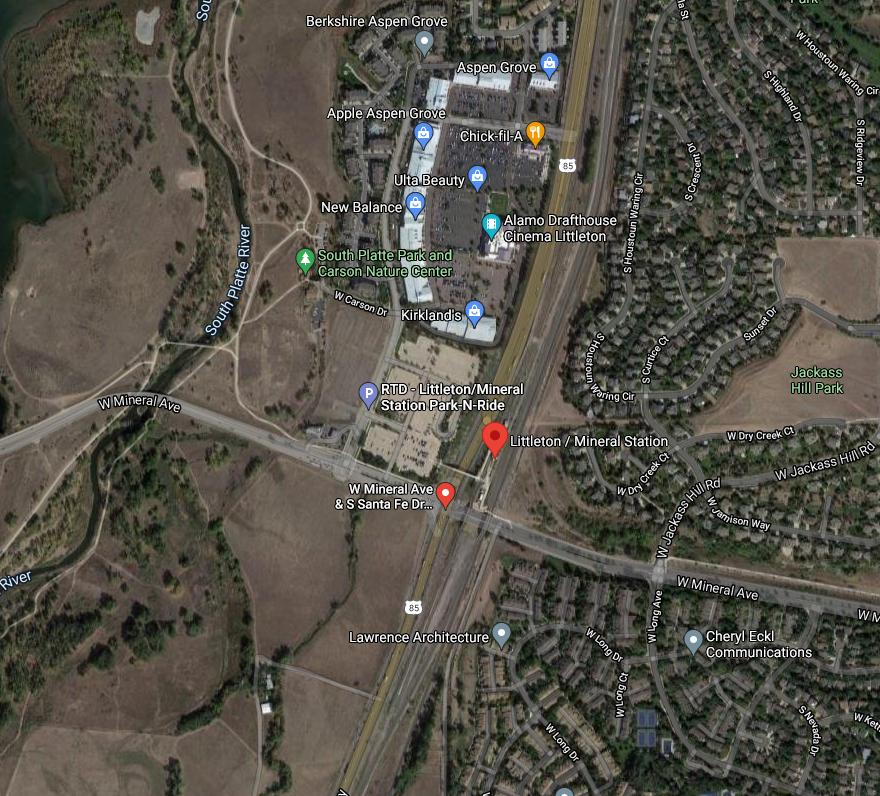

Image via Google Maps.

An article in the Denver Post earlier this year began with a story on how Littleton is struggling to fund a project to “relieve congestion at one of its most troublesome intersections” and how they are now hoping for the federal government to come through with those funds. The project, as described on Littleton’s website, is the Santa Fe Drive and Mineral Avenue intersection, a location that epitomizes everything that is wrong with the American development pattern.

Two corners of the intersection are the congestion-inducing development pattern typical of post-War America. These neighborhoods are the epitome of the Suburban Ponzi scheme, generating a sugar high of revenue early and a disproportionate amount of financial liabilities later on. This approach is not only the cause of their congestion problem, but also the root cause of Littleton’s fiscal crisis.

One corner of the intersection is a large parking lot that serves the commuter transit light rail line. Here we have the pinnacle of wasteful transit investment: an expensive rail line to a parking lot. Absolutely no value created, no value captured, and, apparently, it’s not doing much for congestion reduction either.

North of the massive parking lot is the collection of upscale strip malls surrounding (another) massive parking lot. This complex itself is surrounded by multi-family housing. The people who live there are, by zoning code, neatly segregated from coming into casual contact with both the middle-class shopping area and those in the higher-priced homes on the opposite side of the stroad known as Santa Fe Drive. (Don’t fret, there is an expensive pedestrian overpass in place to keep traffic flowing).

Of course, the remaining corner, the undeveloped land in the southwest, is for future growth. Maybe they can land a big box store or a gas station! Wholly implausibly, people in a decision-making capacity in Littleton apparently believe this will help their budget woes, despite the case study in fiscal imprudence that they themselves embody.

If you want to see the exact opposite of a Strong Towns approach, this intersection is it.

For those of you interested in the national infrastructure debate, here’s the kicker: Not only has this disaster only been made possible by past federal transportation grants and spending, here’s the future plan to double down as presented on the Littleton website:

There may be some relief on the horizon for those who commute through the Santa Fe and Mineral intersection. The City of Littleton has secured a $9 million grant to ease traffic congestion at the intersection. Littleton staff applied for and were awarded a grant for the intersection as part of the Transportation Improvement Program from the Denver Regional Council of Governments.

If additional federal funding becomes available in the next four years, another $6 million could be allocated. The project requires a 20% match of $1.8 million dollars in local funds.

We need to stop talking about our national infrastructure strategy in terms of Democratic versus Republican approaches. Both parties are falling all over themselves to fund these kinds of projects. What we need to talk about is a top-down versus a bottom-up approach. That is where the reform must come, and it starts with the way that we talk about it.

Littleton would never be building this stuff if they had to fund it themselves. And it’s not like we’re doing this because the rich cities are banding together to help those places less fortunate. Littleton is a rich city; its median household income and median home value both exceed state averages by sizable margins. Why does Littleton need transportation subsidies? Why is the rest of American paying for them to harm themselves in this way? What are we doing here?

What we’re doing is what we’ve been doing for the past 75-plus years. That model is broken and we need to change it. That change is not likely to come from Washington D.C. nor from any debate over infrastructure funding, at least not in the coming months. It’s going to come from thousands of communities across North America deciding they are ready to become a Strong Town.

The latest book by Charles Marohn, Confessions of a Recovering Engineer: A Strong Towns Approach to Transportation (Wiley & Sons), will be released this September. Get your copy and learn when the Confessions Book Tour is going to be near you at www.confessions.engineer.

In this episode of Upzoned, co-hosts Abby Newsham and Chuck Marohn talk about satellite communities and the psychological phenomena that incline people toward large projects.