The American Alley, Part 2: Origins of the American Alley

This article is the second in a four-part series we launched this week on American alleyways as promising sites for incremental infill development. Read part one here. The author, Thomas Dougherty, will be the guest on Thursday’s episode of The Bottom-Up Revolution podcast. You can also download the e-book we created for this series for free, which features bonus content not shown on the website!

As an urban form, alleys have almost completely escaped the attention of historians. No “history of the alley” has been written, and few other resources can be found. What is pieced together here is a collection of references from books and articles, often themselves bemoaning the lack of historical account regarding alleys. Yet knowing the history of the alley (and being able to differentiate the historic alleys of Philadelphia with the service alleys of later American cities) is key to recognizing not only why they were once so useful, but why they are underutilized in many cities today. Understanding the alley’s past reveals it for what it is today: a hidden resource for making our cities stronger and more prosperous.

From left to right: Boston, MA (1640); Cambridge, MA (1637); New Orleans, LA (1770); St. Augustine, FL (1770).

Why Early Colonial Cities Didn’t Have Service Alleys

English Colonial Towns

Early American colonial cities had no service alleys, the rights-of-way that run along the backs of urban lots. English colonies such as Boston (1630), Cambridge (1636) and Providence (1638) developed informally without city plans. Settlers simply built according to urban sensibilities brought with them from Europe.

Boston developed organically; the streets are said to have simply “followed the cow paths.” Cambridge was developed along roughly orthogonal streets, and Providence built itself along a single high street. None of these early colonial settlements lent themselves to the development of a service alley.

Spanish and French Colonial Towns

Spanish and French colonial settlements were developed along more formal urban theories. However, though they were often laid on a grid, they never included an inner-block service alley.

Spanish settlements such as St. Augustine, Florida (1573), followed the principles of the Laws of the Indies, giving it a central plaza and other archetypical features. New Orleans (1722), the largest of the French river towns, was composed of 300-foot x 300-foot urban blocks. As these cities developed, passages (sometimes called “alleys”) were often created running perpendicular to the streets, giving access to rear courts. However, no service alleys, like the kind found today running down the center of historic American urban blocks, were included in the layouts of these cities.

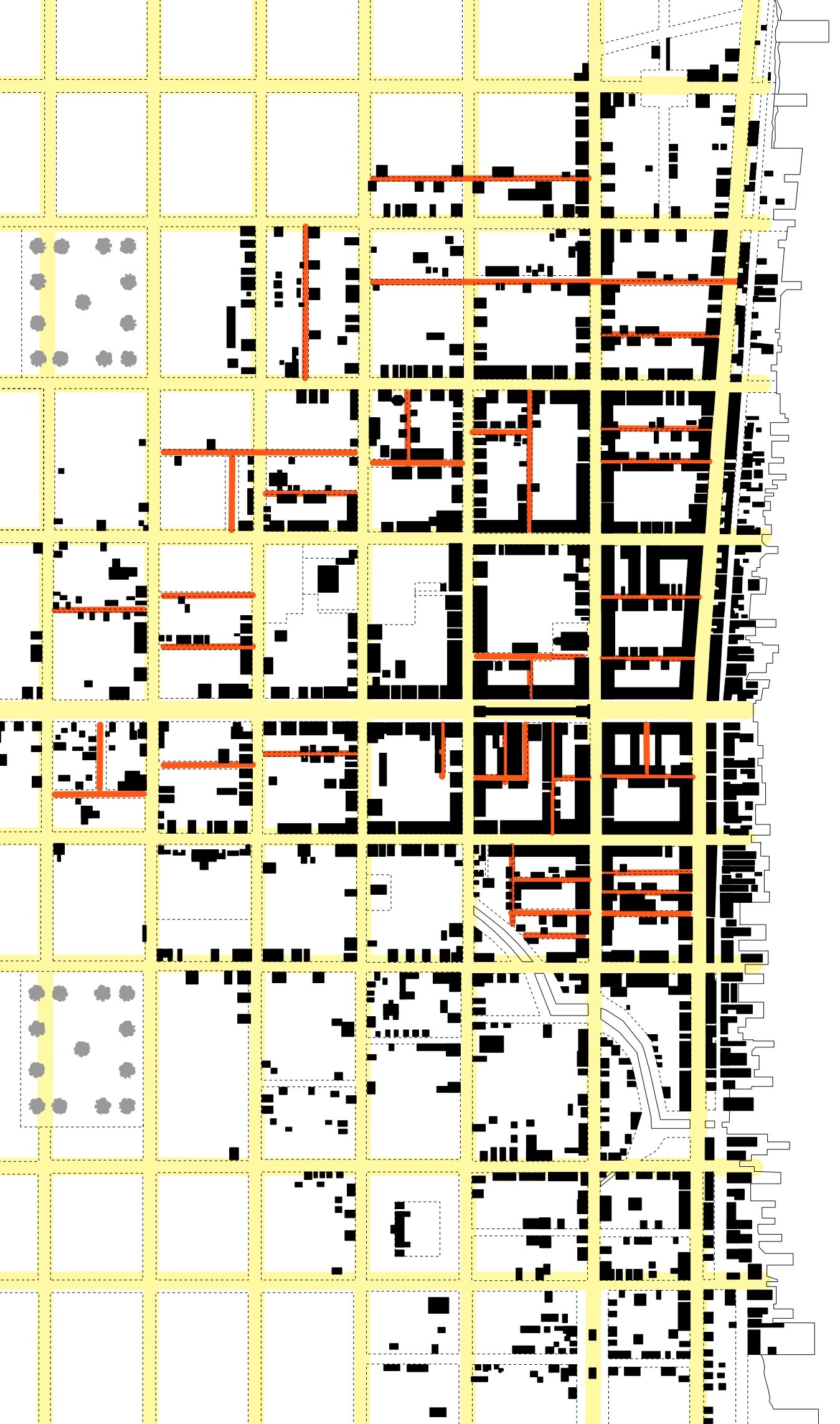

Partial plan of Philadelphia (1702), showing planned streets in yellow and minor streets in red.

Philadelphia’s Inner-block Alleys, or “Minor Streets”

Minor Street: A pedestrian-scaled, inner-block street formed by buildings and walls that “front” the street.

Philadelphia (1682)

Philadelphia was the first British colony to be laid out according to a formal master plan. Designed by William Penn in 1681, it was a visionary plan and by far the largest proposed city of the New World, at the scale of London and Paris. Penn’s design was influenced by the 1666 Great Fire of London, and the subsequent plans for its redevelopment. Penn envisioned his city as a “garden city” with straight, wide, tree-lined streets in which the filth, disease, and fires of London would never exist. The plan of Philadelphia did not include service alleys.

A minor street in Philadelphia today.

But Philadelphia did not develop according to Penn’s vision. The city was built up along the Delaware River because of the economic significance of its wharf. As the city developed from the Delaware River to the Schuylkill River, small paths or lanes were created by the property owners as shortcuts through the grid of blocks. These lanes could be later claimed by the city as public throughway if they had been used for 21 years, or if the landowners brought the lane to the court, donating the land in exchange for its upkeep by the city. These later came to be known as “minor streets.” In the figure at right, the major street network (highlighted in yellow) is clearly visible, with the minor streets (in red) cutting though the block and doubling or even tripling the street network of the city.

The most famous of Philadelphia’s minor streets, and the nation’s oldest residential street, is Elfreth’s Alley. In 1706, John Gilbert and Arthur Wells agreed to a joint land lease, where their properties met between front and second streets, to open a cart path as a shortcut to the wharf. As the years went by, small brick buildings were built along the path, and eventually it became a residential street known as Elfreth’s Alley, subsequently adopted by the city. Today, 32 buildings dating from between 1720-1830 line the street.

Elfreth’s Alley, 1792.

Elfreth’s Alley today. (Image via visitphilly.com)

Though it has the name “alley” in its title, clearly this street is not being used to service the backs of buildings along a major street. Instead this street is formed by the fronts of buildings. Elfreth’s Alley is not an alley as we commonly use the term today, but rather an inner-block street, or “minor street.”

Between 1840 and 1850, the population of Philadelphia grew by 60%, developing far outside the original platting of the city. The dense living conditions had become extremely tight, and the inner-block minor streets (called alleys) were plagued with disease and debris. Reformers and city officials saw the alleys and the people who lived in them as the worst parts of the city and society.

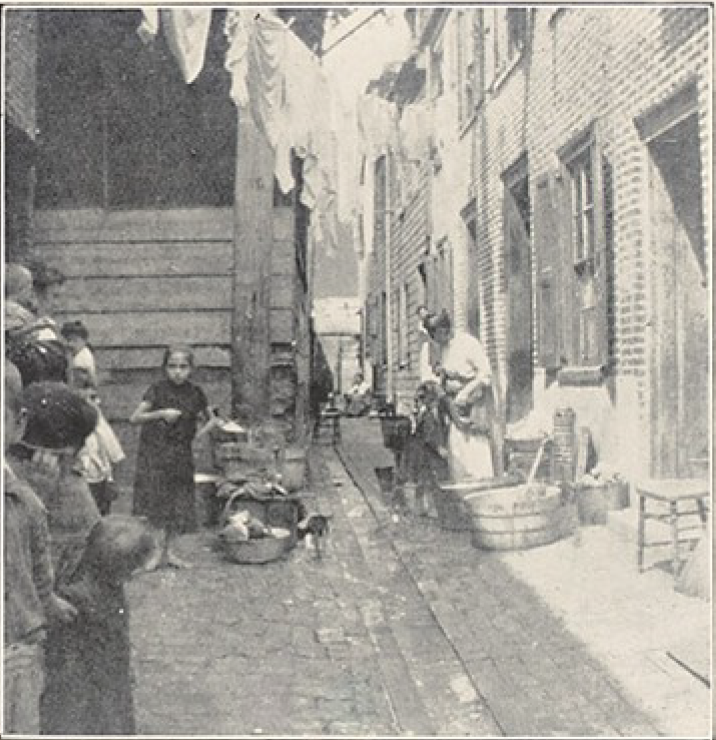

Small inner-block courts and alleys, first developed by the working class, had devolved into slum housing for the poorest in the city. Public transportation had allowed for a greater segregation of social classes, leaving the small row homes within the block to the poorest. In a 1904 study it was noted that small, three-story alley dwellings originally built to house one family were now being subdivided and occupied by three families.

Housing conditions in Philadelphia, 1904.

Social and housing reformers advocated for new laws to make inner-block development illegal, and they called for the demolition of many of the existing minor streets and courts. The unsanitary aspects of industrial city living were exasperated by their narrowness. However, it was not the form itself that was the problem, but the overcrowding of residents and the arrangement and dilapidation of water wells, latrines, kitchens, and other infrastructure that led to the unsanitary conditions.

In 1855 a city ordinance was passed prohibiting the development of any residential building along a street narrower than 20 feet. In 1895, buildings codes were passed requiring multifamily buildings to maintain eight-foot side yard setbacks, even on 25-foot-wide lots. These and other ordinances largely stopped the development of new inner-block development in Philadelphia.

As the demand for housing subsided, minor street development turned to middle-class picturesque housing courts and tree-covered pedestrian streets, rather than the cramped conditions of before. One of these is St. Alban’s place, a residential development built in 1870. St. Alban’s was composed of townhouses facing a pedestrian way, complete with fountains and a central flower garden. This was achieved by raising and paving an existing gridded street.

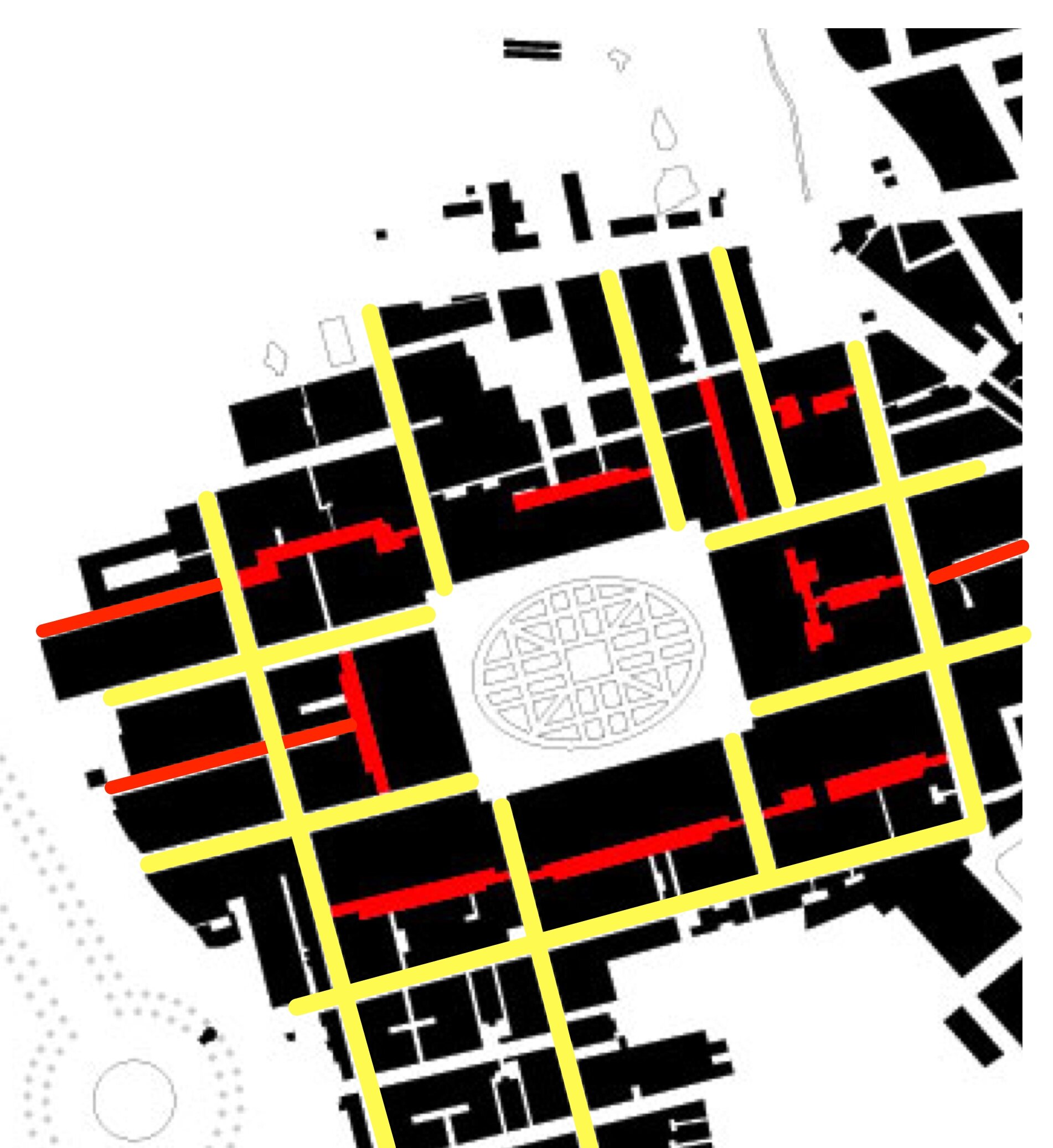

Grosvenor Square; major streets in yellow, mews streets in red. Image via Genealogy of Cities.

Service Alleys of America

Service Alley: The American service alley is generally understood to mean a common right of way that borders the backs of urban property lots. Alleys today are often home to services such as trash collection and parking for the buildings that front the major street.

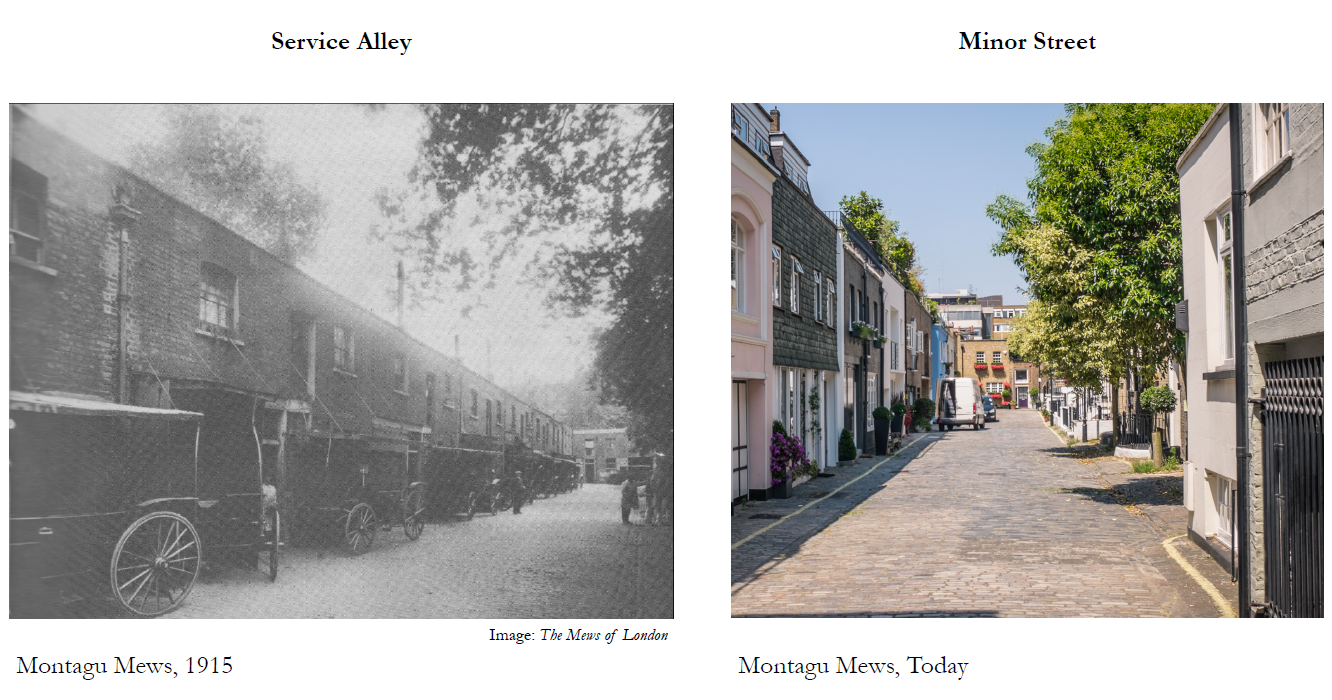

The service alley did not appear in America until 1733, a century after the founding of Boston. Their origin can be traced to the British Mews of London and this history must begin there.

London (1666)

In the early 1600s, horse-drawn coaches had become popular among the wealthy and upper-middle class of London and had begun causing traffic congestion in the city's streets. The carriages were not only creating traffic problems, they were taking up large amounts of space in the city. In 1631, in an effort to address this problem, Inigo Jones created the first service street for carriage stables as part of his design for Covent Gardens. He called the street a “mews,” after the royal stables. These were London’s first inner-block service alleys.

Following the great fire of London in 1666, a critical decision had to be made: whether to rebuild the city according to the property lines that had existed prior to the fire, or to reshape the city according to modern Enlightenment city planning principles. In the end, English law prevailed, and instead of reimagining the city layout, London was rebuilt along the same streets and squares that it had been composed of in 1665.

In response, much of the wealthy upper-class decided to move outside the city. By the early eighteenth century, London found itself in a building boom as land west of London and around Hyde Park was developed. Nobility who owned the land began building speculative development on a large scale, and the layout of these new residential blocks looked to Inigo Jones and Covent Garden as a model. The target market of this speculative development was the wealthy upper class who required accommodation for their carriages and horses, along with their new homes.

Three factors prompted the development of alleys in all of the new West London development:

They were all large upper-class homes designed to be serviced by servants.

The new urban developments were planned and built at the scale of the carriage.

The upper-class speculative planning was greenfield development, which allowed for whole blocks to be laid out at once.

Following Inigo Jones in Covent Garden, the developments included mews streets that divided the block, giving access to stables in the back. These were lined with two-story carriage houses which often also served as the living space for the coachman and his family.

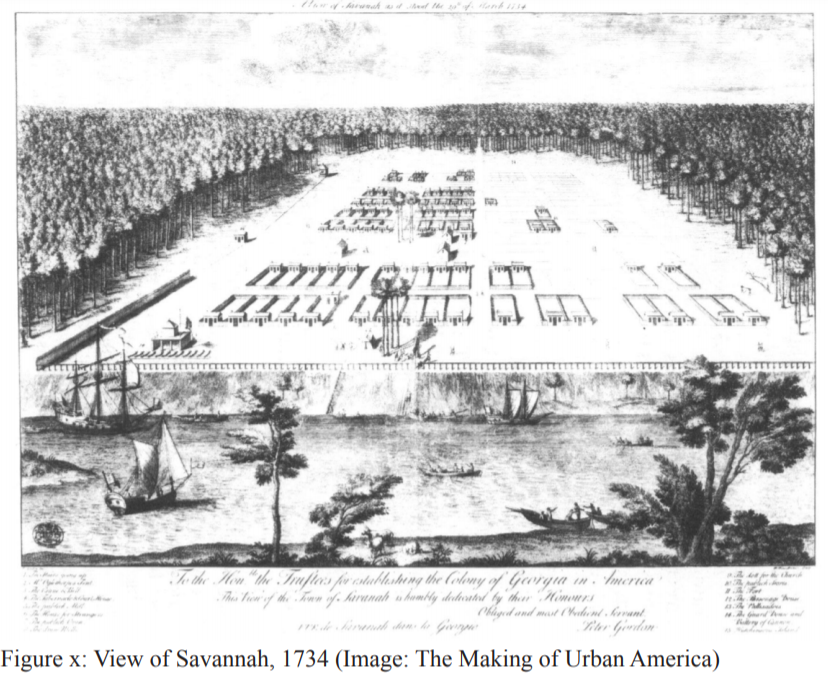

Savannah (1733)

“It is difficult not to conclude that the squares of Georgian London furnished the models after which the plans of Savannah and the other towns of the colony were fashioned.” — John Reps, The Making of Urban America

In Savannah, the service alley (or “lane,” as mews were often called in England) was brought to America. In 1733, James Oglethorp, former military commander and member of British Parliament, was commissioned to found Savannah. The colony was a speculative development and some of the trustees of the project were also involved with the new developments west of London.

Savannah’s ward system is a unique urban model that can be credited at least in part to the ingenuity of Oglethorp. Though there is no preceding model for the ward layout, the use of the service alley found direct precedent in London mews.

It was the service alley as platted in Savanna, rather than the “minor street” found in Philadelphia, that became standard for the inner-block of American cities. Though all the towns of the Georgia Colony were laid out with service alleys, it did not become standard practice in America until the turn of the nineteenth century. It was then that cities, including Columbus, Detroit, and Chicago, were laid out or re-platted with service alleys.

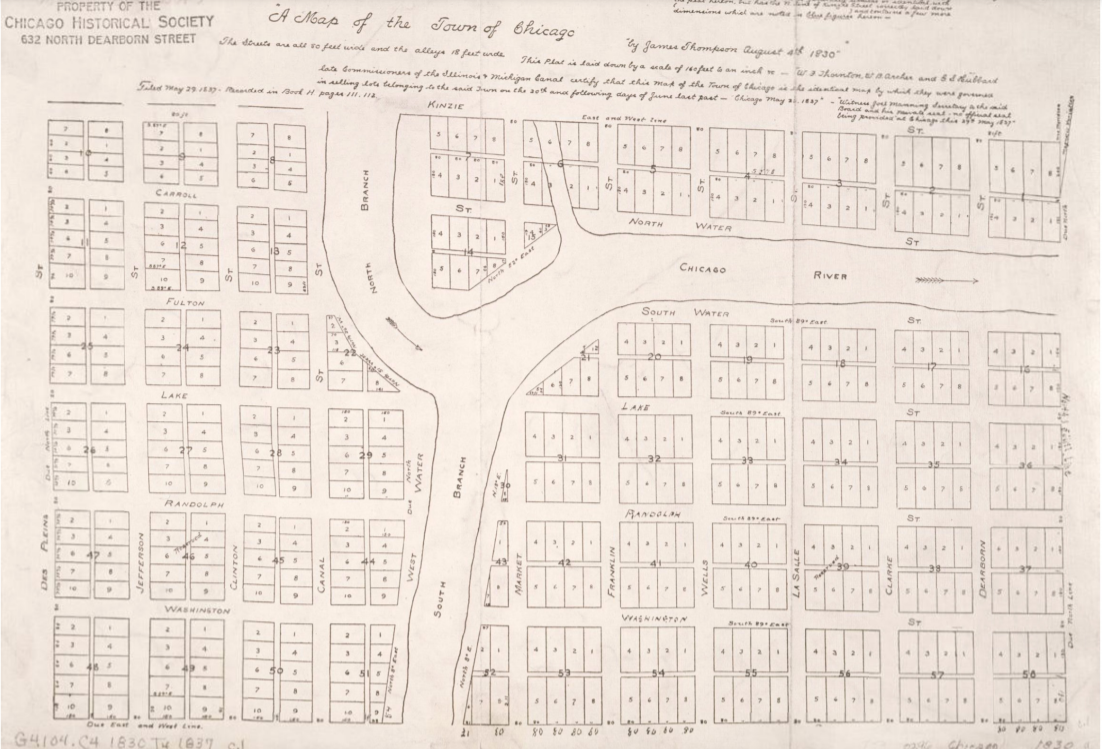

Chicago (1830)

When James Thompson laid out the city of Chicago in 1830, all 58 blocks included service alleys running parallel to the main street and through the center of the block. The streets were laid out on a regular grid, with 66-foot-wide streets, and 16-foot-wide alleys. Though the urban form was primarily the same as the London mews, the use had changed somewhat. In London, the mews had served simply to house horse stables for the upper-class. In Chicago, it became home to the unsightly aspects of industrial city living. The Chicago alleys were dirty places and served as the septic system of the city. Latrines, water wells, kitchens, coal deliveries, and horse stables all found a home in the alley.

Chicago embodied the development pattern of the American Midwest. The Chicago block is laid out along the lines of the continental grid and is typically 330 feet x 660 feet, reflecting the measurement system of the Gunter’s Chain. As cities and towns were developed across the Midwest, they were laid out as gridded blocks with streets and service alleys.

By the mid 1800s, service alleys intended for city infrastructure often became the refuge of the poor in the increasingly dense cities across America. Here, in places never intended to be lived in, shacks sprang up.

Two main factors led to the development of alley dwellings in cities across America during this time: The constraints of pedestrian movement in an industrial city, leading to dense city centers, and the ability of small developers to capitalize on unbuilt inner-block land through the construction of rental structures.

Washington, DC (1865–1877)

Service alleys did not exist in the original L’Enfant Plan of the City of Washington, but were added to city blocks in the early years of the city’s development.

DC developed later than many American cities, and did not reach its pedestrian size constraint until the mid-1800s. “As the city grew, property owners in 1852 cut up the first five big blocks, inserting alleys and selling off the back lots; the process spread,” wrote James Borchert in Alley Life in Washington. The city quickly expanded and developers built both alley and primary street residences simultaneously. “Various sources suggest that, from 1865 until 1877, blocks were often subdivided into street facing and alley-fronting land prior to lot development … and that alley construction could occur before street development, with street development, or as fill-in later.”

In 1894, DC housing reform activists pushed to eliminate all dwelling in alleys, and Congress passed measures to limit their construction and use. Forty years later, Congress created the Alley Dwelling Authority with the mission to discontinue all living along alleys by 1944. Before alley dwellings could be completely eliminated however, a countermovement emerged to restore the alleys on Capital Hill and Georgetown. Borchert writes, “Alley dwellings that began as housing for working-class whites, and which became ‘mini-ghettoes’ for black residents following the Civil War, have recently become expensive and highly sought-after residences for affluent Washingtonians.”

The push to eliminate alley dwellings in the nation’s capital and the minor streets of Philadelphia were part of a broader movement to move life away from the inner-block in modern cities. That same movement also helped speed the demise of the accessory dwelling unit (ADU). To fully understand the opportunity cities have today in rediscovering the productive capacity of alleys and ADUs (the focus of Part 4 of this series), we need to dig deeper on how we turned our backs on them in the first place. That’s the topic of Part 3, which will be released tomorrow.

All images provided by the author.

Thomas Dougherty works as an architect in West Chester, Pennsylvania, where he lives with his wife Rose and three children. He holds a Master of Architecture and a Master of Architectural Design and Urbanism from the University of Notre Dame.