Financial Meltdown

(Source: Unsplash.)

Last month I shared my Christmas Cookie Inflation Index, an admittedly whimsical and non-comprehensive measurement of inflation I use as a device to share otherwise inaccessible economic ideas with our audience. While the overall feedback was positive, there was a strong negative reaction from a small group of our readers. I’m good with that—we all learn a lot from a healthy discussion on areas of disagreement—but some of it quickly became very personal and antagonistic. That reaction piqued my interest.

Let me start by acknowledging some things. First, national Republicans have long run around screaming like Chicken Little that inflation is coming as a result of our reckless fiscal and monetary policy, that it will doom us all, and that we urgently need to cut benefits for the poor and vulnerable (but not the military or corporations they like) to make the government fiscally responsible. This argument is simplistic, hypocritical, and offensive to a lot of people. I think aspects of this argument are correct, but I don’t align with most of it, especially how it manifests in policy.

Next, national Democrats have long run around screaming like Chicken Little that we are in [fill in the blank] emergency that requires us to spend lots of money now with the insincere promise that we’ll figure out whether it makes financial sense later (unless we just change our economic theory to support our policy, in which case we can just ignore the need for fiscal prudence). Spending money on [fill in the blank—housing, college education, health care, etc.] without addressing the feedback loops negating that spending (or worse) with higher prices seems myopic and incompetent where it’s not merely populist, pandering, and self-serving. I also find it deeply destructive to the things I care about. I think aspects of this argument are also correct, particularly the motivations, but I don’t align with it, either.

I start with these two acknowledgements because I understand how even a discussion of inflation affirms the worldview of those with Republican-leaning sensibilities and threatens those with Democrat-leaning sensibilities. For many years, I’ve been writing about macroeconomic issues as they intersect the Strong Towns conversation. I want to assure those of you that are sensitive to the national political conversation that I don’t blame President Biden for inflation, nor do I credit him for low unemployment, just like I didn’t blame President Trump for high unemployment during the pandemic, or credit him with causing the stock market boom during his term.

I’ll vote in elections, but I’m not motivated by national politics, especially the horse race 11 months out from the next ballot. I know many of you are. Please dial it back for the next couple of minutes, or just skip this article altogether. That’s your trigger warning.

The thing I’m most interested in exploring is the idea that inflation is good. In my December article, I described this as the fourth stage of the inflation story.

Stage 1: There won’t be inflation.

Stage 2: There is no inflation.

Stage 3: Inflation is transitory.

Stage 4: Inflation is good.

If you think inflation is good, you are almost certainly sitting at, or very near, the apex of privilege in our society. Either that or you’re in for a rude awakening. Let me elaborate.

I’m going to skip discussing the causes of inflation and merely look at the effect: rising prices. Who is it in society that most benefits from an environment of consistently rising prices? Stated another way: Who is privileged by an inflationary environment, at least to start with?

Well, people who own things that go up in value benefit from rising prices. I bought a brand new car three years ago. It’s paid off and I have 28,000 miles on it. My car-buying plan has long been to buy new and then drive it until it can’t be driven anymore (my last vehicle had over 300,000 miles). I was in the dealer the other day getting it serviced and discovered my car is now worth more in dollars than I paid for it. I’m wealthier (in dollar terms) because I own a car. That’s crazy, but that’s inflation.

That’s just a car and it’s a modest amount, but someone who owns a house, a factory, an oil well, a piece of stock, or any number of things where the value is priced in dollars is seeing their wealth increase relative to what they once paid for things. Now before people shout, “but your dollar now buys less,” sure, but I needed to have a car either way. So long as my stock portfolio, house, and the like go up faster than inflation, I’m doing well.

Likewise, people who have a lot of debt tend to benefit from inflation, especially where that debt is at a fixed rate over a long duration. I own a home and I’ve watched my house price rise—in Zillow terms—from $220,000 to $335,000 over just the past year. Even if I give a substantial amount of that appreciation back in a correction, my mortgage looks better now than ever. And, in dollar terms, I’m a lot wealthier just for owning a home. Since my mortgage is subsidized by the federal government, I’m locked in with low interest rates over a long duration and now can enjoy this advantage as long as inflation runs hot.

People whose skills and services are in high demand have pricing power and can use that favored position to stay ahead of inflation (at least for a while). Again, using myself as an example, I’m a civil engineer with an urban planning degree and many years of experience. Even if I were not working for Strong Towns, I’d have a lot of demand for my services. My wife is a journalist and, likewise, is pretty sought after (she’s really amazing), so she can easily switch jobs if a better opportunity arises (for any loyal MPR listeners, she has no plans to do so). As a married couple in the peak demand years of our careers, we have a lot of options and opportunities to leverage our position to stay ahead of inflation. That applies to many—maybe most—professionals between the ages of 30 and 55 (my wife and I are both 48).

The profile, then, of someone who benefits from modest levels of inflation is a professional-class person or family with high fixed-rate debts and ownership in things that will go up in price faster, hopefully faster than inflation erodes their relative value. If that’s you—and what we know about our audience suggests it likely is—then, congratulations. You are among the most privileged in our society and should be slightly better off in at least the early stages of an inflationary economic environment.

It’s a little silly to talk about who will suffer most in an inflationary cycle since the level of suffering really depends on how severe the inflation is and how long it persists. Those in privileged positions can quickly find themselves behind the curve. Inflation is an accelerating cultural phenomenon, one the comfortable should fear more than they do, a waterfall we fish near the edge of at our peril.

I’ve heard it said that deflation destroys economies, but inflation destroys societies. I believe that to be true.

Consider especially the broad and expanding group that suffers under inflation, a group I am arguing has already suffered under decades of the mild inflation embraced by most modern economists. That list includes people who do not own things that go up in value; renters, people without a retirement portfolio or future inheritance, people who don’t own businesses or make real estate investments. This group has limited upside benefit from inflation, few things they can leverage to stay ahead of the crush of lost purchasing power.

The list of sufferers also include those whose debts are largely in variable rate accounts. That includes people with large amounts of credit card debts and people who regularly access payday loans (or off-book loans, if you understand my meaning). These people already struggle with high interest rates (and threats of broken limbs); accelerating inflation increases their already suffocating risk of getting buried and, ultimately, limits their options for making ends meet.

Among the sufferers will also be people who lack negotiating power when it comes to their wages. While current labor market volatility has given wage earners more power than they had two years ago, they are still the most vulnerable in an inflationary environment. If your job can be replaced with a machine (especially one that will increase in price due to inflation) or if your job can be replaced by a typical unemployed person, then you generally lack the bargaining power that will allow you to stay ahead of inflation. Your day-to-day essentials will go up in price, but your earnings won’t keep up.

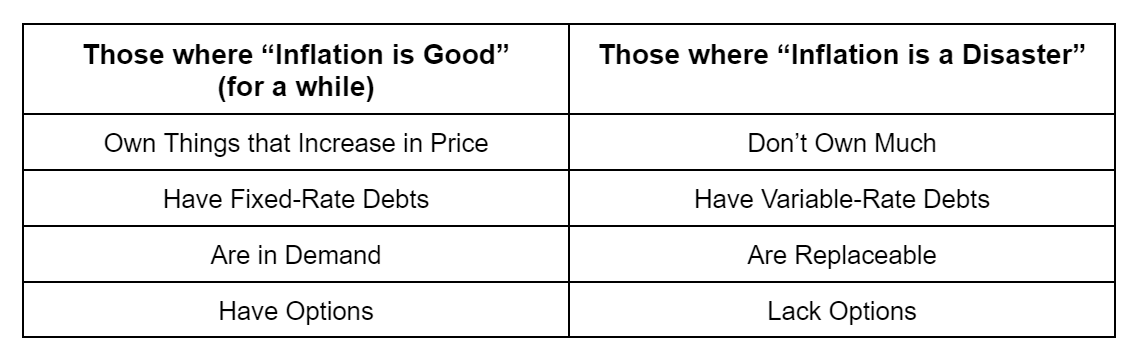

Let’s summarize:

The list on the left looks a lot like the affluent while the list on the right looks a lot like the working poor. The list on the left looks a lot more like Twitter and the list on the right more like Facebook. (Trigger warning reminder!) Politically speaking, the list on the left is not exclusively Blue America, but it looks like the core of Blue America, while the list on the right has a lot more overlap with the Red America that has emerged over the past two decades, especially the unsympathetic parts of Red America that are particularly looked down upon.

Upton Sinclair said that, “it is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” We can take that insight a step further and observe that a lot of the “inflation is good” arguments originate on Twitter, not Facebook. Those conversations are a byproduct of the professional class, not the working class. It is very human to find it easier to believe something when you directly benefit from it, and to discount the discomfort of a policy approach when you are distant from that suffering.

Many of you (in the left column) are going to argue that you support a broad social safety net for just that reason, that something like universal basic income, health care for everyone, and a myriad of other things are necessary to make sure the vulnerable don’t suffer. Okay, sure, those are great intentions, but we didn’t do that first. We were never going to do that first.

Collectively, we did a bunch of other things first. We fought wars and built roads, but we also expanded entitlements for the middle class and threw resources at the [fill in the blank] crisis. And we borrowed enormous sums of money, intellectually scoffing at the idea of a balanced budget, insisting to ourselves that it was as antiquated, and as harmful to the poor, as the gold standard.

The poor are on the front of the marketing brochure, but their plight is not what motivates us, at least not if we’re judged by our deeds, by what we did first. Decades of steady (and underreported) inflation has suffocated the poor, but it’s been great for stocks, housing, and the professional class, which is our highest priority.

Every time I’ve written about inflation or macroeconomic policy in general, there is a vocal contingent in this audience that wants to put me in a box with heartless policymakers who push for austerity, ostensibly because they have no compassion. I reject that.

Others who are more generous regarding my motivations still insist that it’s an old-fashioned viewpoint to want the fiscal discipline of running surpluses, limiting debt, and creating slack in the system. Well, okay, I acknowledge my “old fashioned” view is the minority one. Intellectually, I lost that argument years ago. And now we really have no viable option except to run this high inflation experiment for an extended period of time, unless collapsing the entire economy is an option you prefer. (Some do—that’s crazy.)

This is not a good policy, it’s just the only macroeconomic policy choice still available. The rest are not choices, merely consequences.

Deflation destroys economies, but inflation destroys societies. It’s okay to align with a national political party or persuasion so long as you can step back and see how the dysfunction in that binary is doing great damage to our society. As Strong Towns advocates, we need to get beyond simplified talking points meant to polarize and paralyze (“inflation is good, inflation is bad, Biden did this, Trump did that”) and see our neighbors as humans, many more of whom are now going to need our love, compassion, and assistance as we struggle through what seems like a long overdue economic reset.

—-

January 30, 2022 Update: It’s a Sunday afternoon and I was reading the Minneapolis Star Tribune when I came across this story: Inflation hits Minnesota's smaller cities and rural areas harder than Twin Cities. The article bolsters my central thesis, that being, if you’re sitting around wondering why the ignorant rubes in Red America are obsessing about inflation and not something you find more urgent, there is good reason to believe that their experience is substantially different than yours.

Charles Marohn (known as “Chuck” to friends and colleagues) is the founder and president of Strong Towns and the bestselling author of “Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis.” With decades of experience as a land use planner and civil engineer, Marohn is on a mission to help cities and towns become stronger and more prosperous. He spreads the Strong Towns message through in-person presentations, the Strong Towns Podcast, and his books and articles. In recognition of his efforts and impact, Planetizen named him one of the 15 Most Influential Urbanists of all time in 2017 and 2023.