Less Parking Lots, More People Space

Parking lots (indicated in yellow) in downtown Houston, TX.

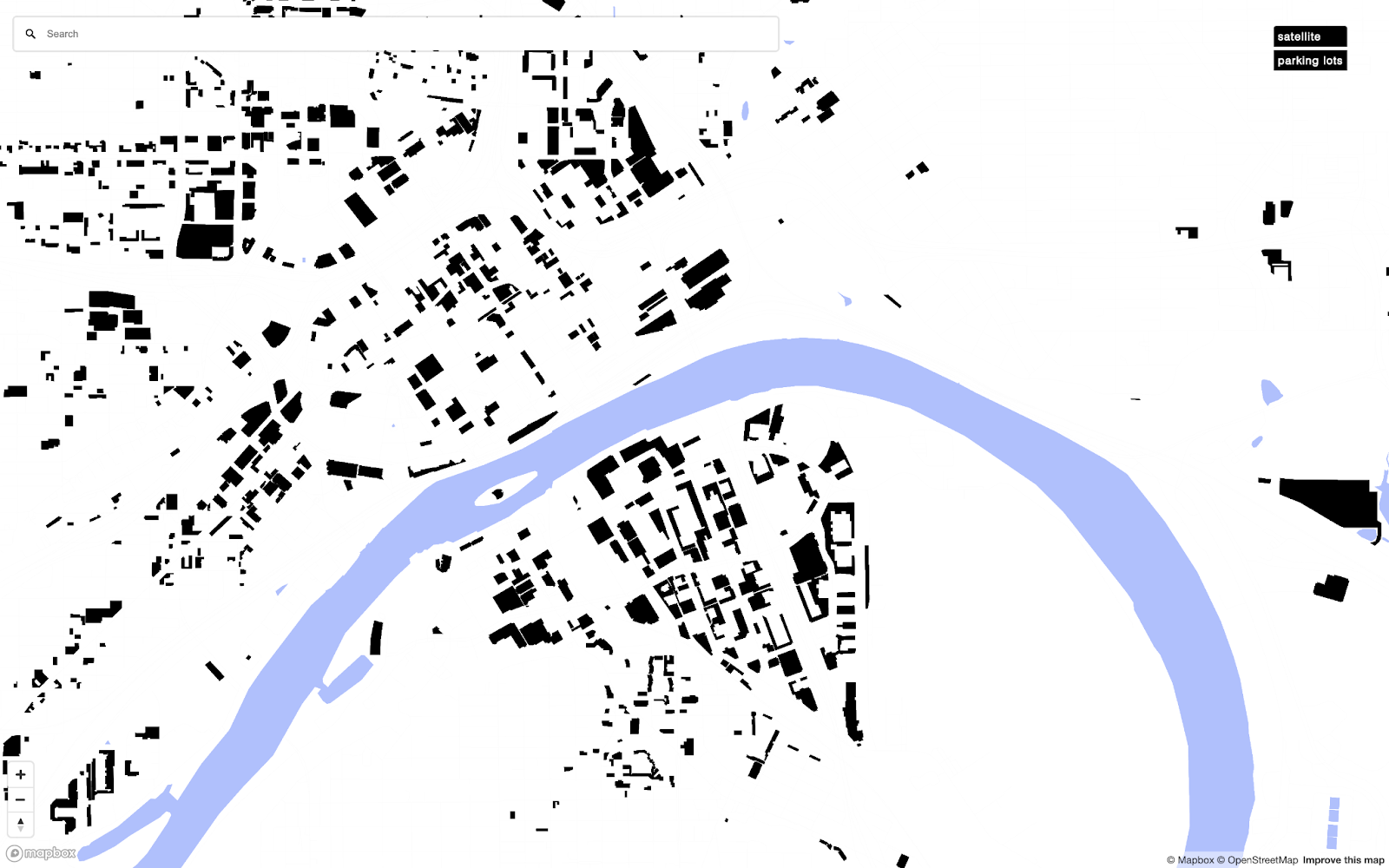

City space is finite. Even though every new construction requires some amount of parking, no American city collects data on its total parking supply. In the hopes of addressing this problem and outlining just how much space we dedicate to parking, I created an interactive map of (almost) all the parking lots in the United States. I’m interested in the possibilities that could come from informing and positioning people to affect the way these urban structures shape all of our lives.

Imperfect, as it was created with open-source data (from OpenStreetMaps), this map still does a pretty good job of illustrating a simple fact: We waste too much land in our cities and towns on vehicle storage.

This is an abbreviated version of the map, but you can view the complete interactive map here. Take your time, look around, and see how much of your city space is dedicated to parking. You can zoom in or search for your city, and toggle satellite mode—which will help you see just how much additional parking was not included in this public dataset.

Imagine the sheer mass of all that asphalt.

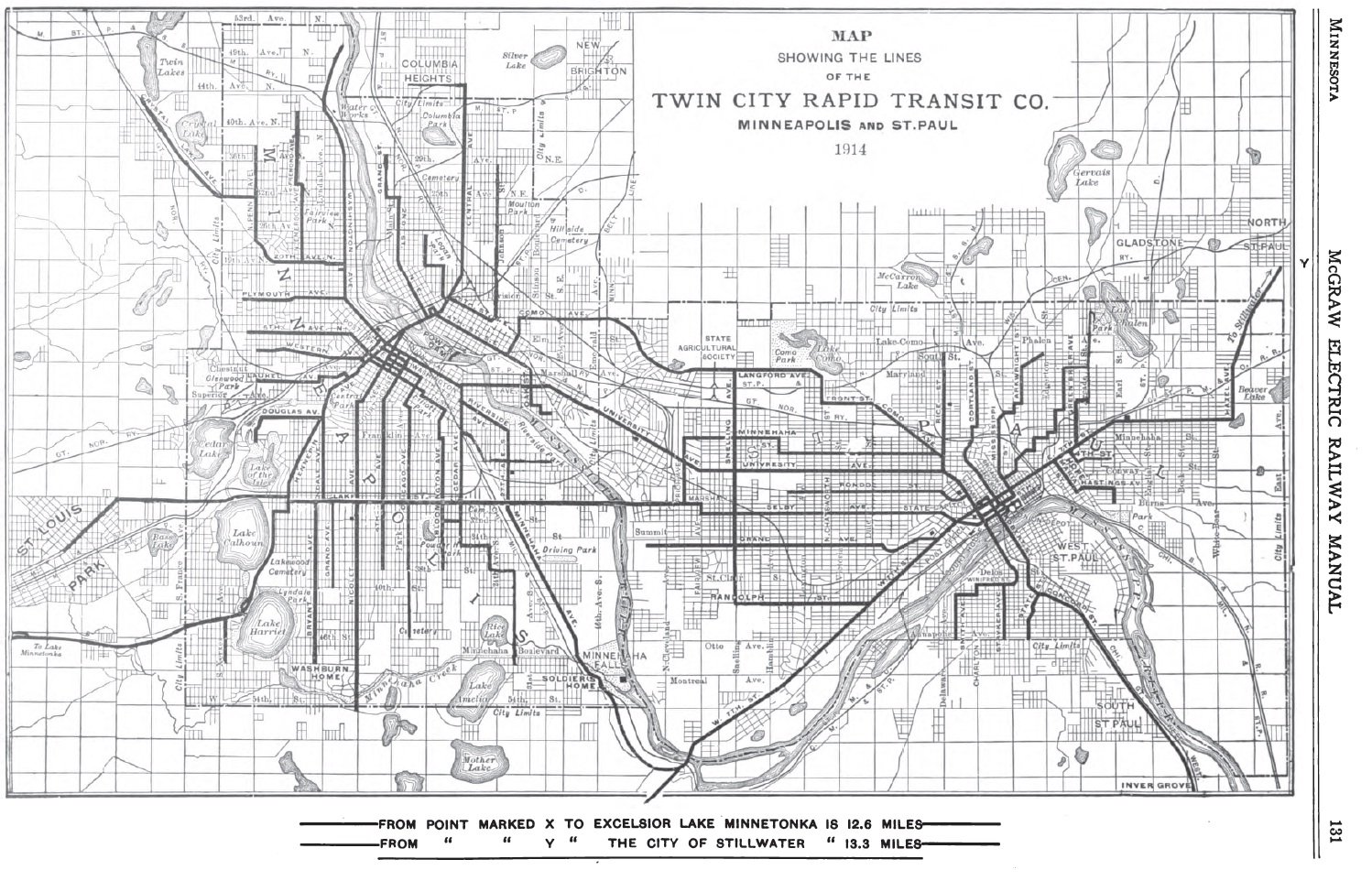

I’m a graphic designer and I made this map as part of my thesis in college. After spending a semester abroad and experiencing good public transit, I was thinking about the transit system in the Austrian town (population 50,000) I lived in and how monumentally more convenient and connected it was than in the American city (population 425,000) my college was in—i.e., Minneapolis. I was obsessively comparing the two…until I learned about the transit system that used to exist in Minneapolis and the tragic dismantling of its streetcar system, along with most other streetcar systems in the country. Then, I began comparing the Minneapolis of 100 years ago to how it looks today.

(Source: Collin Knopp-Schwyn and Senori.)

The above image is an example of what we could still have today, and I was heartbroken to learn about what our country had lost in terms of public services in transportation. These days, it's impossible to imagine a transit system like this but the truth is, America was once the world’s leader in urban rail line supply.

The present day map above does not include buses, but even if it did, it would be only marginally less pathetic. A two-dimensional map doesn’t reflect the complete reality of a system. Its geographical coverage is one thing, but an infrequent bus schedule with few stops that leaves riders with long wait times during frigid Minnesotan winters—that’s the reality of this deprioritized, decayed public transit system.

I couldn’t afford a car as a student and was forced to be a pedestrian and a bus rider. In general I didn’t mind, as I liked traveling light, by foot, bike, bus, and sometimes carpool. Without a car, I was free from being tied to a small room on wheels, from thinking about where I left it or if I’d left it unlocked, if someone had broken into it, if I had enough gas, or if I was going to get a parking ticket. Although not owning a car gave me some peace of mind, it was definitely more work to take Minneapolis’s public transit—more planning, coordinating, and walking—not exactly an easy way to get around. It wouldn’t have been as much of an issue if the city had just maintained its old, more efficient and more abundant, public transit system.

The last year of college is usually spent working on a final thesis project. Initially, I was thinking of doing a project comparing the transit system of Minneapolis 105 years ago to today. Since seeing the comparison of the two maps, I’ve been captivated by the story of the sabotage of America’s transit systems. I wanted to create something that could illustrate to Americans that we used to have an amazing transit system and we were not always dependent on the car, or even the bus, and that there used to be streetcars on most streets.

I thought about making an app to compare the two systems. I wanted to dig into the historical archives of my city to pull out the old system schedules, so I could build the schedule into an app that compares how much more efficient the old system would have been than our current one. As cool as I still think that would be, the more I thought about it, the more it felt in vain—like I was just romanticizing an old system I could never bring back. So, I refocused on something current that I see as an opportunity and that could possibly affect a living human’s experience of our built environment.

Wandering around the city, I began noticing how much parking lots were ruining my walking experience. They were massive black holes that sucked up potentially vibrant city space—just big, boring puddles of asphalt. Pedestrians are not considered at all in the design of parking lots; it’s all about the vehicle. Most of the time, there aren’t even paths for people to safely walk on in parking lots.

Beyond the human experience of a parking lot, having so much asphalt around impacts the environment in a number of ways: it absorbs heat from the sun, meaning parking lots warm cities up simply by existing. Asphalt is also derived from petroleum, which seeps into the soil below—along with any tire residue, oil, and gas sitting on top of the lot—especially after rainfall. Moreover, instead of being active locations where people want to go and that could generate better tax revenue, we just have these passive, paved voids for leaving empty cars in, that are unused for at least 10 hours every night.

Individual parking lots extracted from the map.

It’s not all bad news though, as parking lots have incredible repurposing potential. Parking lots are usually located in PRIME city-center locations. They could be converted into productive public and private spaces where humans can spend time, engage in activities, and meet each other. Imagine If your neighborhood parking lot became a park, a public square lined with food trucks in the evenings and fruit vendors in the summer, or a new housing structure with a grocery, laundromat, and coffee shop?

After noticing and learning more about parking lots, I realized that this was the forward-looking topic I was looking for. My intention for this project became to demonstrate just how much city space is allocated to parking and hopefully spark some thought about what they could potentially become.

As I’m a designer and not a surveyor, I had a ton to learn about collecting the specific geographic data I was looking for. That took about the first half of the year. The second half of the year I spent formatting and styling the data, as well as coming up with a fictional campaign to promote the idea of converting parking lots into places for humans. My hope is that when people interact with this map, they’ll recognize how much potential their cities have, waiting to be unlocked, from these asphalt-covered spaces.

Here are some photos from my final thesis installation. As a supplement to the map, I created a book holding 10% of the parking lots in Minneapolis (around 850 lots!) and a wall installation of all the parking lots in a one-mile radius of the campus, with tags showing their square footage.

These parking lots are blank slates: perfect sites for development. I like thinking of them as time capsules of land. They’ve been preserved in asphalt for us to uncover their new uses for city- and town-dwellers of tomorrow. They are taking up space that has the potential to become livable, walkable, and human-centered.

What could serve your community better than these parking lots?

(All images for this piece were provided by the author.)

GET READY FOR #BLACKFRIDAYPARKING!

Your parking lots are too big to fill, even on the busiest shopping day of the year. Here's how you can help use that land for something greater.

Katya Kisin is a graphic designer currently working at a letterpress shop in San Francisco. She's a recovering digital designer with a deeply buried love for print, and is often preoccupied thinking about how the design of spaces and objects shapes human experience and quality of life. You can connect with Katya on Instagram @katkisin.

Dallas wasn't built for the car: it was paved over for it. This new bill can help it rebuild.