Yet Another Exploding Whale: ODOT’s Freeway-Widening Cost Doubles

This article was originally published on longtime Strong Towns contributor Joe Cortright’s blog, City Observatory. It is shared here with permission. All images for this piece were provided by the author unless otherwise indicated.

One infamous clip on YouTube depicts the handiwork of Oregon Department of Transportation engineers: Over 50 years ago, in the fall of 1970, confronted with the rotting corpse of a 45-foot-long sperm whale on a Pacific beach, ODOT engineers planted half a ton of dynamite under the carcass. When detonated, it created a rain of blubber that sent bystanders running for their lives, a huge chunk crushing a nearby car. ODOT has subsequently given up on exploding stranded whale carcasses (it now carefully buries them). But it has found another thing to explode, and regularly so: project budgets.

ODOT then: exploding whales. ODOT now: exploding budgets.

The I-205 Abernethy Bridge: Now Twice As Expensive

For some years, the idea of widening and seismically retrofitting the I-205 Abernethy Bridge across the Willamette River between Oregon City and West Linn (in Portland’s southern suburbs) has been on the wish list of state and local transportation officials. The Legislature didn’t fund the project as part of a major transportation package in 2017, but did direct ODOT to produce a “cost to complete” report so that it would have some idea of how much money would be needed. ODOT produced that report in 2018. It said that retrofitting and widening the bridge would cost $248 million. (The bridge project was identified as “Package A” in this cost estimate.)

Armed with that figure, highway advocates pushed forward, and in getting the Legislature to direct ODOT to take on the project. But—and we know you won’t be surprised—ODOT’s estimate was wrong. Very wrong. When the project went to bid this spring, bids came back at just a shade under $500 million. What that means is that ODOT will have to divert money from other construction projects, or as is currently being debated, charge even higher tolls for travel on I-205 (if tolling is approved for the project by federal, state, and regional officials). This is actually the second big cost bump for the project since its 2018 “Cost to Complete” report. Less than a year ago, in the Fall of 2021, ODOT prepared a “construction phase cost estimate” of $375 million, which represented a 50% increase in costs. As is common practice, the original 2018 estimate was officially forgotten when reporting the further escalation of costs in 2022, with ODOT reporting only the additional cost increase of roughly $125 million, not the full cost increase of $250 million from its original estimate. The key takeaway though, is that, in the space of just four years, the cost of this project doubled.

I-205 Abernethy Bridge. (Source: Wikimedia Commons.)

The irony here is that tolling is likely to depress the level of traffic demand on I-205 sufficiently that added lanes aren’t needed, which would obviate much of the need for the project. But because ODOT has put the construction of the project ahead of final decisions on tolling, there’s a high likelihood that it will end up building vastly more highway capacity than there is demand. West Linn and Oregon City could end up looking like Louisville, with an expensive and largely unused toll bridge as a kind of financial millstone.

Deja Vu All Over Again

Regular City Observatory readers will no doubt have a sense of deja vu. Only last fall, we wrote about how the Oregon DOT’s I-5 Rose Quarter freeway project had yet another cost overrun, with total costs estimated to range as high as $1.45 billion. That in turn was an increase from a previous cost increase, announced just 18 months earlier, in which the project doubled in cost from the estimate provided to the 2017 Oregon Legislature. The project, which was sold to the 2017 Oregon Legislature as costing $450 million had its price tag balloon to almost $800 million in March 2020. That Rose Quarter freeway widening project is now in financial and legal limbo: ODOT hasn’t identified a new source of revenue to pay for the ballooning costs, and the Federal Highway Administration has rescinded the project’s “Finding of No Significant Environmental Impact” in the face of a legal challenge.

ODOT: Where Cost Overruns Are Just the Way We Do Things

To some, a cost increase of this magnitude may seem like an aberration. For anyone who has followed ODOT closely, its apparent this is very, very common. Over the past decade and a half at least, ODOT has blown through the budget estimates of virtually every large project they’ve undertaken.

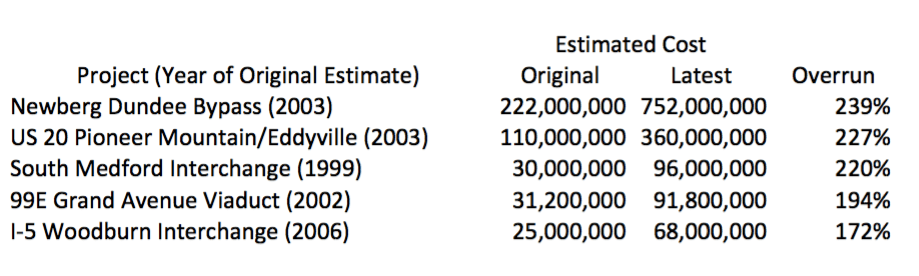

Like other highway agencies, ODOT has consistently underestimated the cost to complete its major highway projects. A review of ODOTs own reports for the largest projects its undertaken in the past 20 years shows a consistent pattern of cost overruns, as summarized here:

(Note: Newberg Dundee estimates are for entire project, which is only partially complete. Other projects latest cost reflect total cost as completed. Source: Compiled from ODOT reports.)

There’s abundant academic evidence about the consistent tendency of “megaprojects” to overrun early cost estimates. Bengt Flyvberg has literally written a book about it.

The problem isn’t unique to Oregon. Two of the biggest bridge projects nationally (rebuilding the Tappan Zee Bridge of NYC, and San Francisco’s Bay Bridge West Span both produced colossal overruns).

No Accountability for Overruns

There have been furtive efforts to oversee ODOT. In November 2015, Governor Brown said she was commissioning a performance management audit of ODOT.

ODOT did nothing for the first five months of 2016, and said the project would cost as much as half a million dollars. Initially, ODOT awarded a $350,000 oversight contract to an insider, who as it turns out, was angling for then ODOT director Matt Garrett’s job.

After this conflict of interest was exposed, the department rescinded the contract in instead gave a million dollar contract to McKinsey & Co. (so without irony, ODOT had at least a 100% cost overrun on the contract to do their audit).

And what McKinsey produced amounted to a whitewash, as I explained at Bike Portland. The audit covered up a long series of ODOT cost overruns, and instead focused on a long series of meaningless measures of internal administrative processes, such as the average time needed to process purchase orders. Meanwhile, the state’s million dollar auditors excluded from their cost overrun calculations the U.S. 20 Pioneer Mountain project, the single most expensive project that ODOT had undertaken, and even though excluding it, managed to understate and mislabel the 300% cost overrun.

The final report from McKinsey recommended that ODOT could become more efficient by giving more money to consultants like McKinsey (as humorist Dave Barry would say “I’m not making this up”).

Which, in a way, brings us full circle: Dave Barry was one of those principally responsible for popularizing the exploding whale story. With ODOT, the explosions just keep coming, but now they’re confined mostly to destroying project budgets, rather than raining blubber. At least with whales, ODOT learned from its mistakes. When it comes to massive cost overruns, it’s simply become the way this agency does business. We give the last word to Barry, who narrates the whale explosion:

So they moved the spectators back up the beach, put a half-ton of dynamite next to the whale and set it off. I am probably not guilty of understatement when I say that what follows, on the videotape, is the most wonderful event in the history of the universe. First you see the whale carcass disappear in a huge blast of smoke and flame. Then you hear the happy spectators shouting “Yayy!” and “Whee!” Then, suddenly, the crowd’s tone changes. You hear a new sound like “splud.” You hear a woman’s voice shouting “Here come pieces of… MY GOD!” Something smears the camera lens.

Joe Cortright is President and principal economist of Impresa, a consulting firm specializing in regional economic analysis, innovation and industry clusters. Over the past two decades he has specialized in urban economies, developing the City Vitals framework with CEOs for Cities, and developing the city dividends concept.

Joe’s work casts a light on the role of knowledge-based industries in shaping regional economies. Prior to starting Impresa, Joe served for 12 years as the Executive Officer of the Oregon Legislature’s Trade and Economic Development Committee. When he’s not crunching data on cities, you’ll usually find him playing petanque, the French cousin of bocce.