Seven Stroads That Have Been Converted to Streets

This article was originally published on Public Square: A CNU Journal. It is shared here with permission. All images for this piece were provided by the author.

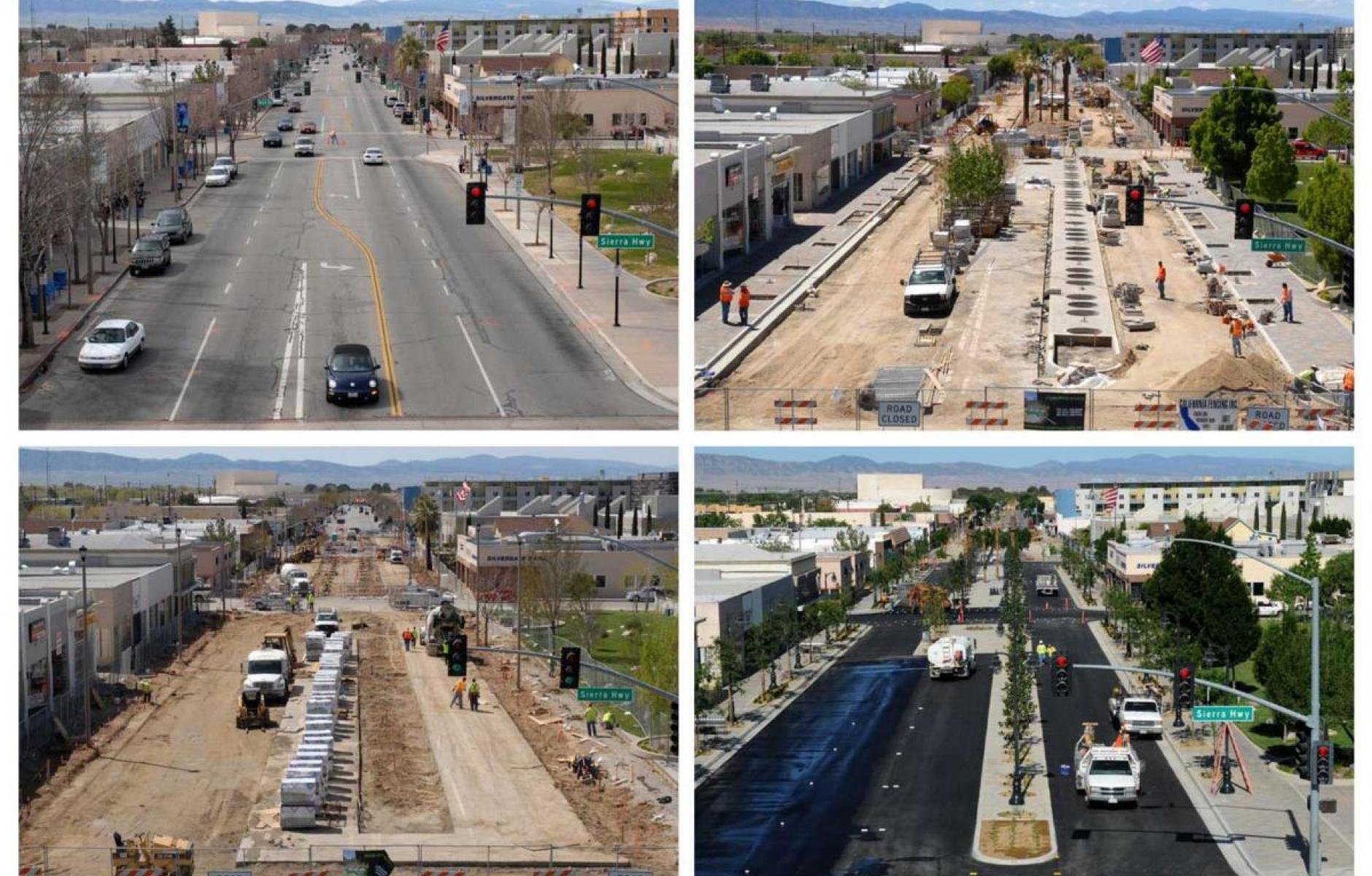

The making of Lancaster Blvd. in Lancaster, CA. (Source: Moule & Polyzoides.)

A “stroad”—a term coined by Charles Marohn of Strong Towns—is a thoroughfare that combines the complexity of a street with the design speed of a road. Stroads include the most dangerous thoroughfares in America, and they don’t serve the functions of either a street or a road very well.

There are thousands of stroad sections in the U.S. and transforming a good number of them is important to the goal of improving quality of life and mobility in cities and towns.

Here’s a list of seven places where stroads have been successfully converted to streets.

Lancaster Blvd., Lancaster, CA

Of all of the stroad-to-street conversions in the U.S., Lancaster Blvd. may be the most admired. A five-lane arterial was converted to two lanes with a central landscaped “rambla” that is inspired by the famous boulevard in Barcelona. Diagonal parking is placed in the center, but the median also includes crossings and small public spaces. During seasonal festivals and regular events, like a farmers’ market, the rambla is entirely given over to public space. Here’s what CNU wrote about Lancaster Blvd. in Public Square:

This strikingly original street redesign had an enormous economic impact on Lancaster, a suburban city in the desert of southern California. A street that previously held minimal attraction to pedestrians, and had little sense of place, suddenly became the social, cultural, and economic heart of the city.

Aerial of Lancaster Blvd. (Source: Moule & Polyzoides, Architects and Urbanists.)

For all its attractiveness, Lancaster Blvd. was lean, both in cost and time of construction. Existing curbs were maintained and the entire nine-block-long, $11.5-million project was completed in eight months. Not to mention, it spurred an impressive amount of economic development.

Main Street in Providence, Huntsville, Alabama

There are two kinds of stroads: The first kind begins as a street and then is converted to a stroad through widenings and other changes. The second was originally designed as a road (or suburban stroad), and gains complexity through development. Most of the projects on this list are the former, Main Street in Providence is the latter—and this kind can be even more difficult to transform, because it lacks even the distant memory of a street.

In this traditional neighborhood development (TND) in Huntsville, a five-lane suburban artery has been converted to a Main Street with on-street parking and a center tree-lined median.

Developer David Slyman on the arterial road twenty years ago.

The tree-lined thoroughfare today. (Source: Nathan Norris.)

The transformation of the thoroughfare is a pioneering change for this suburb. The City of Huntsville gave back the outer two lanes for on-street parking, and after over a decade of battling with the fire marshal, the middle turn lane was rebuilt as the tree-planted median—completing the vision of an urban boulevard.

Outdoor dining on Providence's Main Street. (Source: Nathan Norris.)

North Monroe Street in Spokane, WA

Spokane narrowed this commercial street from a five-lane stroad into a three-lane street with parking and nice streetscape features. The mile-long project cost $7.1 million.

“It’s become a unifying signal for our neighborhood,” Taylor Phillips told the Spokesman-Review. “We have folks that are really coming together, because now they feel safe to go up and down Monroe. They feel like it’s welcoming. They feel like it has a place for them.”

(Source: The Journal.)

The effort was not just a wonderful road diet, but the process won over local opposition, says Dean Gunderson, a planner commenting on Pro-Urb, a listserv for urbanists. The city split the construction into two contracts so that it could be finished sooner, and worked with the Small Business Administration to provide support for businesses. A grant program helped businesses to improve their facades, magnifying the impact.

La Jolla Boulevard, San Diego, California

Travel lanes on this stroad in Bird Rock, San Diego, were reduced to two from five, with modern roundabouts calming traffic and allowing for the elimination of turn lanes at intersections. On-street parking was added to both sides, including diagonal parking on the west side, closest to the beach.

The traffic count remained approximately the same before and after the changes—about 22,000—and yet La Jolla Boulevard has been transformed to a walkable, pleasant street from one that was hostile to pedestrians. Average speeds were reduced from 40–45 mph to 19 mph. Noise levels dropped 77% and retail sales rose 30%. Traffic crashes fell by 90%.

La Jolla Boulevard, before and after. (Source: Dan Burden.)

Main Street, Hamburg, New York

Travels lanes on a 1.9-mile stretch of U.S. Route 62, which goes through the center of Hamburg, New York, were shrunk from 21 feet wide to 10 feet wide. That extra asphalt was used for on-street parking and 4-foot painted buffer lanes between the parking and travel lanes. Roundabouts were installed in four locations, slowing traffic to 15 miles per hour at main intersections.

These changes made Main Street a “main street” once again, where businesses and street life thrive. Completed in the summer of 2009, the Route 62 project is widely credited with catalyzing the revitalization of the village—working in concert with other efforts. Concurrently with the reconstruction, New York State Office of Community Renewal provided $800,000 in matching Main Street Program grants for façade improvements—leveraging more than $7 million in private investment in 33 buildings.

Main Street looking west, toward a modern roundabout. (Source: Dan Burden.)

Hillsborough Street, Raleigh, North Carolina

Four lanes of traffic were reduced to two on this busy thoroughfare separating the campus of North Carolina State University from city neighborhoods. The rebuilt thoroughfare is more appropriate to the context of the adjacent walkable neighborhood that is lined with institutional, commercial, and residential buildings. Two roundabouts were installed. A central median was built.

The road diet reduced crashes along the thoroughfare, which had been listed as the most dangerous roadway for pedestrians in the state. It also improved business along the street, where on-street parking was doubled.

Hillsborough Street, Raleigh, after redesign. (Source: Kimley-Horn and Associates, © CJ Walker Photography, Inc., All Rights Reserved.)

Route 30A, Seaside

Before the development of Seaside, Florida, Rte. 30A was designed to enable cars to go 50 to 55 miles per hour, and yet the road still provided beach access along 18 miles of Gulf Coast. This highway traveled through the heart of where developer Robert Davis built a town, starting in the 1980s.

At the time, Walton County had little in the way of government planning oversight, and Davis gradually took over the shoulders of the highway for on-street parking and landscaping. Development fronted the street on both sides, and pedestrian activity steadily grew. All of these changes created friction—so that by the 1990s, cars naturally slowed to 20 miles per hour, or less, inside Seaside. Seaside has a lot of congestion today, including people on foot and bicycles constantly crossing 30A. On busy days, cars go through Seaside today at a steady snail’s pace.

Other new towns have been built along 30A, and a bicycle and walking trail has been built along the thoroughfare. The county is now planning a transit system, possibly using autonomous vehicles.

Airstreams and tables along 30A in Seaside. (Source: Nathan Norris.)

Robert Steuteville is editor of Public Square: A CNU Journal and senior communications adviser for the Congress for the New Urbanism.