Mansion Blight: How the Most Expensive Homes Drain Community Wealth

(Source: Unsplash.)

Every time your local elected officials tell you they don’t have money for park maintenance, public school teachers, or basic public safety measures, remember this: They’re only telling part of the story.

In reality, there are more resources available, but tax assessments are being eroded by local property tax breaks received by homes in the highest range of values: Mansions on large lots, not rundown properties in low-socioeconomic-status neighborhoods, are the real blight on a community’s financial health.

What I’m describing here is not the work of some malicious bureaucrat or a cabal of county staffers plotting how to make the rich richer. It’s a tragedy of bad math. My local government uses some supremely flawed formulas and techniques to generate these valuations—and yours may very well be making the same mistake.

You haven’t voted to approve this tax break, of course. It's a quirk of the math, baked into the way your local property values are calculated. In this system, the wealthy are clearly and repeatedly advantaged.

My firm, Urban3, has analyzed property tax records in many places and we’ve seen this happen all over the country. I’d like to highlight my hometown of Asheville, North Carolina, as one example. (You can play this game yourself in your community if you can get the property assessor’s data. Check your local county government’s website to see if they have a GIS portal and start poking around.)

What’s worse, the assessed values of mansions drop precipitously over time. Why? It’s unclear, but it’s happening.

Thirteen-thousand-square-foot Spanish Mediterranean 1926 Mansion, on 22 acres. (Image: Buncombe County.)

The above eyesore designed by Addison Mizner, a prominent Florida architect from the 1920s, is one of my favorites.

Weighing in at a modest 13,426 square feet of livable space, this worn-out shack is choked in on a meager 21-acre lot abutting the beautiful Blue Ridge Parkway. In North Carolina, our assessment law says a property’s assessed value should be equal to what someone would pay—but apparently this hovel would be tough to market. Assessed at a “priced to sell” $3 million total value, that roughly converts to a discount of $7 million from comparable nearby sales. This translates to $37,000 in local tax relief every year. Those champagne wishes and caviar dreams aren’t cheap, so every bit helps, I suppose. By the way, $37,000 is the base annual salary for a public teacher in our community. Think about that: One house’s tax break is equal to one teacher’s wages.

Here’s the real kicker, though: in 2011, this house was assessed at about $4 million. Adjusting for inflation, it’s dropping a whopping -54% of its value as of this year, according to the county assessor's office. Meanwhile, the average house in my city has increased in value by 273% over the same period. Apparently, there is no desire for wealthy folks to move here.

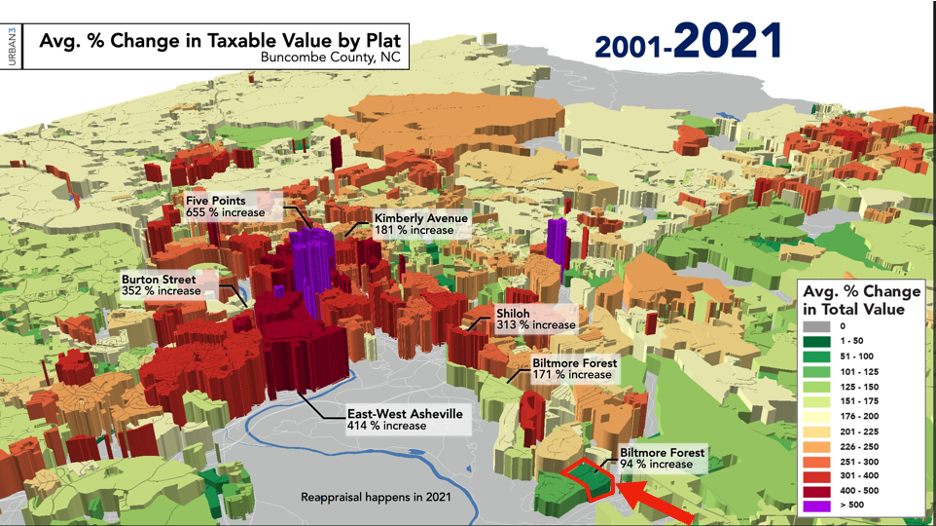

This highlighted neighborhood in Biltmore Forest only increased in value by 94% over 20 years. (Image: Urban3, using Esri software.)

This is clearly affecting other nearby properties. If we were thinking about this like any other kind of neighborhood blight, we’d be reacting with serious concern! Take the example above: If we look at its neighbor, it’s losing over $4 million of assessed property value over that same window and adjusted for inflation, resulting in a discount of over $22,000 in taxes per year. If this property’s assessed value did nothing more but keep pace with inflation, it would be paying $22,000 more in taxes this year—roughly equivalent to the salary of a teacher’s aid. These are not anomalies, nor am I cherry-picking. There is a quadrant of this neighborhood of Biltmore Forest that is totally tanking in taxable value (see above: Biltmore Forest is indicated with an arrow). This just happens to be the wealthiest and most exclusive community in my county, which makes it one of the most desirable communities in the state of North Carolina.

This plague of plummeting assessed values and corresponding tax benefits shows up on the other side of town, over by the country club and golf course. This property (below) sold for $3.9 million. That same year, it was assessed a meager $1.2 million. Because, let’s face it, no one wants a 9,504-square-foot mansion on a 3-acre lot. That buyer must be a total rube. As we know, it’s only an ignoramus that could drop $3.9 million on some hovel. What a sucker! This dump’s assessment has shed about $670,000 in value over the last 10 years. A healthy discount of $3,500 taxes per year, or about a year of gas for a deputy sheriff. Adding to this insult, because the value was set in the 2021 assessment year, the 2022 purchaser gets to enjoy paying the old tax value. For the next THREE YEARS!

This North Asheville shack by the country club sold for $3.9 million, even though it has lost over $670,000 in taxable value over the last 10 years. (Images: Zillow & MLS.)

Like me, you’ve probably seen folks show up en masse to a local zoning board or city council meeting, clamoring and crying that a new duplex planned for their neighborhood will send their property’s market values plummeting. Au contraire! More often than not, that duplex will be way more potent than a single-family detached home and will increase neighborhood value. This translates to more tax generation, not less, which makes it a great deal for all taxpayers. For instance, in Asheville, single-family homes average $1.5 million per acre and a duplex is $4.1 million. On the other side of the country, in King County, Washington, it is $1.5 million per acre and $3.8 million per acre, respectively. Compared to the neighborhood mansions I’ve mentioned above, they’re feebly eking out at $0.1 million per acre and $0.4 million per acre, respectively. Where are the hordes of angry homeowners with handmade signs and coordinated t-shirts, decrying the loss of value to their homes? It seems to me that this blight should be a matter of grave civic concern!

In Buncombe County, we’ve raised these issues with our local government. The burden is on them to fix what’s wrong. If they are serious about repairing the harm caused by decades of inequitable and unfair practices, they need to correct this misplaced welfare for the wealthiest folks in our county. We’re distributing over $5,000,000 every year in tax breaks to the richest people in our community—this isn’t the Feds, the U.S. Congress, or even the state legislature—these are decisions made at the local level, by elected officials who live here in Buncombe County.

This same government earned praise in 2020 for being among the first local governments in the U.S. to pass a resolution acknowledging the deep damage of racial inequity and calling for reparative solutions. If they are now going to live up to the resolution’s rhetoric, they can start by addressing the problems I’ve pointed out here. Otherwise, they may as well hit the delete button on that resolution.

Joseph “Joe” Minicozzi is the principal of Urban3 and an urban planner imagining new ways to think about and visualize land use, urban design, and economics. Joe founded Urban3 to explain and visualize market dynamics created by tax and land use policies. His award-winning analytic tools have garnered national attention in Planetizen, The Wall Street Journal, Planning, New Urban News, Realtor, Atlantic Cities and the Center for Clean Air Policy's Growing Wealthier report. He holds a Bachelor of Architecture from the University of Miami and Master of Architecture and Urban Design from Harvard University. In 2017, Joe was recognized as one of the 100 Most Influential Urbanists of all time. He is a founding member of the Asheville Design Center, a non-profit community design center dedicated to creating livable communities across Western North Carolina.