Most Public Engagement Is Worse Than Worthless

Ruben Anderson is a long-time member of Strong Towns and consultant on sustainability and regenerative systems. Today he's sharing a guest article in response to Strong Towns founder Chuck Marohn's thoughts on the value (or lack thereof) of public engagement.

Chuck Marohn's Strong Towns article entitled "Most Public Engagement is Worthless" grabbed my attention. The article is fantastic, and the comments are getting richer and richer as I write this. But I would like to go a bit further.

I think most public engagement is beyond worthless. I think it actually corrodes the relationships we need in order to build a strong town. Most public engagement, as it is currently conducted, makes our cities worse places.

Does this mean that I am saying we should abandon public engagement? Most definitely not. But I think we need to understand behavior, relationships, and expertise a lot better if we are going to do good with our consultation efforts instead of harm. Public engagement needs to be done well, because it would be better to do nothing at all than to corrode the public's trust in City Hall and in each other.

Let me tell you a story.

I was working for the City of Vancouver’s Sustainability Group and was assigned to a large urban planning process. Consultation was said to be critical, necessary, jugular—and so we dog-and-ponied with our flip charts and sticky notes and dotmocracy.

We asked people the question, "How could Vancouver be more sustainable?"

Solar Panels! they told us. Windmills! Plant trees! Ban plastic bags! Ride bikes!

Golly. Solar panels?

Here I am working in a Sustainability Department and I never thought of solar panels. How could I have missed that? Solar panels! And bikes? Wow. Just wow. What a fool I was! My eyes are opened!

What I am trying to describe here is how terribly insulting this process was to everybody involved.

We had asked a question that could produce nothing but disrespect for the experts who have dedicated their education and careers to reducing environmental impact. Of course we knew about solar panels.

And we had asked a question that the members of the general public were not equipped to answer, because they aren't experts. There are some good reasons why solar panels are not installed faster—it is almost always a better idea to insulate your home, weatherstrip and draught-proof first. You reduce your own energy demand before you put on solar panels.

When the report and recommendations come out, the public sees nothing that resembles what they asked for—they wanted solar panels and they got weatherstripping. They too feel disrespected. They gave their irreplaceable time, hours from their one and only life, and look what they got.

They had to give something up in order to come to the consultation, and nothing good came of their time because they weren’t asked questions they could meaningfully contribute to answering.

This is not how you build a trusting relationship: a strong foundation on which to work together. This is how you corrode trust.

Another story: the city I now live in, Victoria, BC, recently began installing "all ages and abilities" bike lanes after a significant consultation period. At a couple of the consultations, big maps were laid out so people could draw where they thought bike routes should go.

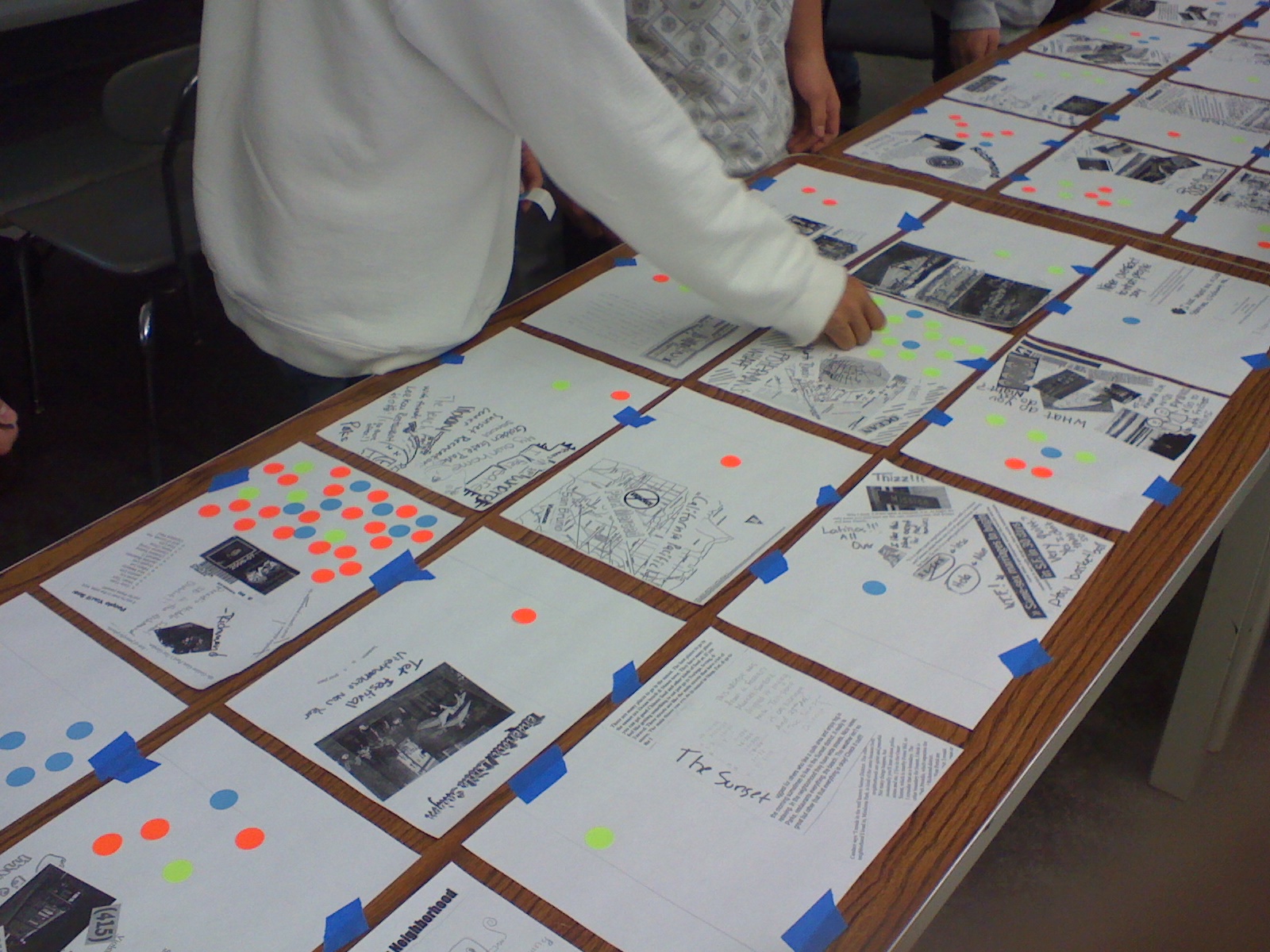

If you're having the public draw bike lanes, think about why. What expertise do they have that your bike planners don't? (Image source: NYC Department of Transportation)

To be quite blunt, if your bicycle transportation planner does not have a very clear idea what routes would balance geography, access, cost, safety, behavior change, etc. then they are incompetent and should be fired.

If your planner is not incompetent, then they are probably well-read on the past couple of decades of practical experimentation with bike infrastructure. They probably know the current best thinking on the sorts of places bike lanes should connect and serve. They have probably seen a hundred examples of creative solutions to integrating bikes into cities. They have been paid by the city to learn these things, and probably have done a bunch more research on their own because they are transportation geeks.

So the public was asked to come in and draw routes. The public doesn’t know anything about how many dollars per kilometer each option costs. They don’t know about lane widths, and how wide the city right-of-way is. They know nothing about other things that may be important, like planned changes in sidewalks, utilities, and developments.

We ask people who have none of the education, experience or knowledge needed to make proper decisions to come in and draw routes, and we ask the City staff to sit there and be polite at the ridiculousness that pours out. Can you imagine how the staff feel about giving up their evening with their family, after a day’s work, to go be polite to people who are unaware of virtually all the limiting factors?

And so the public input is ignored, which in this case is the right thing, and the public feels abused, disrespected, undervalued and duped, which also seems like the logical outcome of the consultation.

What Are We Trying to Do?

I really mean this question. What are we trying to do when we do public engagement?

Why are all these people in this room? What are we trying to accomplish? Before we gather people for public consultation, we need to be clear and honest about what we are trying to do. Then, if consultation is the right solution, we can design a process to fill that need.

Are we trying to get ideas?

Our culture loves Ideas! We have Idea Jams! Idea City! TED Talks!

Lack of ideas is almost never the problem, as I have argued elsewhere. The problems we face are usually a lack of social cohesion or a lack of money—and a lack of money often also indicates a lack of social cohesion; not enough people care about the project to tolerate a tax increase to pay for it.

Even if we did need more ideas, consultation doesn’t work to generate them. I have a degree in Industrial Design, so I actually took classes in generating ideas. As a working designer I had to constantly generate new ideas. I can tell you, there is not much of a worse way to generate ideas than to put a bunch of strangers with competing interests who are untrained in brainstorming techniques into a room for three hours.

Are we trying to build social license?

Superficial exercises like dot-voting often fail to respect and take advantage of the expertise of either professionals or the public, and leave both feeling insulted. (Image source: Wikimedia Commons)

Maybe. One of the knee-jerk responses every planner is familiar with is “There was no consultation.” So, putting out a plate of stale cookies and setting up a sad dot-voting exercise neuters that response. Maybe there was nothing consultative about it, but the sign in the hall said "Public Consultation This Way," so I guess there must have been a consultation.

Bringing many people with different goals together behind one project is quite a big task. Clearly a real program to build social license would take a lot more time and care than your average public meeting. Planners know how to hold value-based discussions, but I don’t know that I have ever seen them use that skill in the processes I have been involved in.

If you need to build social license, maybe you should throw street parties; have a barbecue.

Are we trying to acknowledge people?

I have come to think that engagement tries to acknowledge the public’s plaintive cry, “Don’t forget me.” I think people often don’t need to win; they just don’t want to be forgotten. But as I described above, the outcomes of our processes sure look like they were forgotten.

I wonder what it would be like if the design team went through the plan inch by inch, narrating the compromises, costs and failures, the choices they made, and the specific comments from participants. “Albert and Ruth, who live in Fairfield, are concerned that we expand the songbird habitat. We did that by specifying different landscaping from the typical pop-pom tree and grass lawn. The west side is a native plant garden, intended to be wild and seldom entered by people.”

Are we trying to let off steam?

Issues sometimes get contentious, and letting people vent and feel heard seems like a valid goal—it is just that our public meetings often seem to do the opposite. They actually increase tension instead of releasing it. How could we vent most effectively? Could we play dodgeball? I mean literal dodgeball, where we try to smoke the people we disagree with as hard as we can with a fast-moving ball.

I understand that dodgeball does not resolve what we think of as city planning issues—but neither does the current model of public consultation. And the current model often increases tension between parties, whereas at least dodgeball would dissipate some of it. So there is a very real, serious case to be made that dodgeball would produce better outcomes from our consultations than any amount of sticky notes and dotmocracy ever will.

That is a sad commentary.

Misplaced Expertise

It is clear the public is dissatisfied with much public engagement, and do not feel they were actually listened to.

In the Facebook comments on Chuck's article, Nancy Graham said “A lot of [consultation] is simply for show and to pretend you are being heard when the leaders have already decided the results they want.”

Why would leaders do what they want? Sure, maybe for self-interest and personal profit in some cases. But perhaps it’s generally because they think they know better and are trying to make the world a better place. This belief is not unfounded; presumably, they have years of education and on-the-job experience and privileged knowledge of the tricky terrain of this particular troubling issue.

Expertise is unfashionable right now, partly because our society is not very good at understanding who is expert at what, so we give too much power to some people and not enough power to others.

One of the most enduringly popular Strong Towns articles is Chuck’s Confessions of a Recovering Engineer, in which he lambasts his younger self and his former profession in rich detail. He describes how he would arrogantly ruin neighborhoods and destroy streets, thanks to his confidence that his asphalt was for the better. He was the expert.

He was an expert in engineering, who ruined the place. Citizens were promised something better, but what they got was something worse.

And most of our cities have many Chuck 1.0s. Many of us live in cities that were impaled with freeways through the core. We travel on streets that are unsafe by design. The sense of place does not show up in engineering standards manuals.

And yet it would be silly to break out the dotmocracy to specify how to repave a road. It doesn’t matter how you feel about finely crushed rock compacted in the base layer; it matters how it performs with vehicles on it.

Engineers should be expert in the strength of materials and construction methods. They are in no way expert in human behavior, nor are they experts in public opinion. They should not be making political decisions or urban design decisions.

The engineer’s role, which has grown to have so much influence in so many cities, should really be quite technical and fairly powerless. They should have the job of implementing decisions made by others, and within that, their expertise for materials and construction should be completely respected. They are the experts at that.

Sadly, we don’t see residents as experts. This is a critical and corrosive mistake. Of course, they certainly are not experts in how to reduce greenhouse gases, or pave roads, or pick bike routes. They should not be picking beams for a bridge.

But citizens of a city do know how the built environment makes them feel, and how they would like to feel.

They are experts in how increasing taxes will stress them out. They are experts in hidden secrets of their streets and alleys. They are experts in the amenities they want for themselves and their family. They are the only experts.

Their expertise should be respected.

We should only consult with residents when they are the ones that can best answer the question at hand. But in those moments, they should be treated as the experts they are.

One of the most impactful examples of this I have seen comes from when Oregon had single-payer medicine and was trying to ensure tax dollars were spent most effectively. Experts rated every medical procedure and pharmaceutical by its cost and the quality of life it gave, then ranked them from best to worst. Right up at the top was treatment for pneumonia, and at the bottom was life support for babies born without a brain.

And then they added up the medical costs and the current tax revenue, and drew a line on the list where the tax dollars ran out.

“We should only consult with residents when they are the ones that can best answer the question at hand. But in those moments, they should be treated as the experts they are.”

Medical experts made the list of treatments. And then residents—experts in the impact of sickness on their family and community, and experts in their personal budget—got to decide what should be covered.

Essentially, the public got to choose how many people would die. Would you like to cover more procedures? Simple, just pay more taxes. Should we spend one million dollars per year keeping an 80 year-old alive? Nope.

And so the line is adjusted.

What Chuck describes in "Confessions of a Recovering Engineer" is that the choice of how many shall die on our roads has been delegated to engineers, who prioritize speed over life. That is wrong. Engineers are not qualified to make that choice. Only the citizens are experts in how many funerals they would like to attend each year, and how much tax they are able or want to pay—and it turns out they prioritize safety over speed.

Design Expertise

So far I have talked about engineer experts and resident experts. But in his latest article, Chuck also talked a lot about design, referencing Steve Jobs. In fact, commenter Kevin Adam noted the similarities between Chuck’s article and corporate Design Thinking.

As I mentioned, I have a degree in design and worked as a product designer—so naturally I think design is incredibly important. Designers bring a different expertise to the equation that residents and engineers typically don’t have.

The old joke about the iPhone is that if you asked people what they wanted in a telephone, they would have said, “Longer cords.” That is the product of a worthless consultation.

So to avoid that, Chuck says, “get on with the hard work of iteratively building a successful city. That work is a simple, four-step process:”

Humbly observe where people in the community struggle.

Ask the question: What is the next smallest thing we can do right now to address that struggle?

Do that thing. Do it right now.

Repeat.

Let me reframe this list as a design process.

1. Humbly observe where people in the community struggle.

Almost every word here is pure gold so I am going to break it down.

Humbly...

Arrogant, rock-star designers may be fine for chairs or blenders, but as I have already said, only the residents are experts on living in their city. To get good outcomes, the designer must approach with humility, in service of the city and its people.

...observe...

Asking people what they want is often very ineffective. Most people aren’t trained to imagine seemingly impossible things, like a stylish supercomputer that fits in your pocket.

Good public opinion pollsters have to distill opinions out using oblique questions and the discernment that comes with years of experience. Angus McAllister, CEO of McAllister Opinion Research, said, “Most consultation and opinion research is like eating a Big Mac—empty, unhealthy and dissatisfying. We don’t need Ronald McDonald, we need Anthony Bourdain.”

Humans are poor at noticing the drivers of our own behavior. We often behave for one reason, and then seek an explanation for why we acted that way. Typically we just pick something reasonable-sounding even if it is totally unrelated. This is called Post Hoc Rationalization, and is described in the wonderful study, Telling More Than We Can Know. [Full study here.]

For example, if you ask someone why they come to a certain café, they may respond that it has lots of parking. So, if you remove the parking and they keep coming, you know parking is a post hoc rationalization. In fact, they like the way the light falls on the patio, or the service, or the smell reminds them of their grandparents’ kitchen.

Changing the parking is a design prototype. Nothing happens? Change it back and do something different. It is not just whole projects that need to be iterative; the stages within a project also benefit from iteration.

So good designers have to ask lots of careful questions, but observing behavior is critical. You can ask people what route they walk, but when you observe the paths worn through the grass, you have real data.

...where people in the community struggle.

We hold up Gods of Technology like Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg, but they are solving their own problems—rich tech bro problems. They don’t care about sidewalks or corner stores; they have driverless cars and drone delivery!

2. Ask the question: What is the next smallest thing we can do right now to address that struggle?

A Strong Towns principle is that it is less risky to make many small bets than one huge gamble. It is also often strategic, because it is much easier to get permission to do a small thing.

From a design perspective, it is easier to manufacture a spoon than it is to build a kitchen mixer with hundreds of parts—but both can whip up a cake.

3. Do that thing. Do it right now.

Actually, before you do the thing, I would like to add one more step.

2b. From a design perspective, it would sure be awesome if you would collect some data first, to test your Theory of Change.

Here are some Theories of Change:

If we paint a bike lane here, more people will ride bikes.

If we narrow this road, cars will drive slower.

If we widen this highway, we will eliminate congestion.

So, when we plan our interventions, we are using a Theory of Change—whether we have stated it or not—and it is important to collect data to test your Theory of Change.

Collecting data can be very tricky. For example, if you stripe a bike lane, you may see more bikes on that road. Are they new cyclists, or did the same old cyclists just change routes? If your goal is more cyclists, that matters.

So, collect data that will actually test your Theory of Change. As far as I am concerned, the number of hits on your website is generally useless data. We want to count real world change.

3. NOW you do the thing.

Do the thing, then observe. What actually happens in the real world? What do people do—not what do they say, what do they do? Do they drive slower, ride more, shop locally, add a basement suite, plant a tree—whatever. What do they do?

This lesson is one of my favorite from design school. What people do is the only measure that matters. My teacher said, “The users tell you what your design is.”

Imagine you have designed an amazing bench—but nobody sits on it. The skateboarders, however, love it.

Well, then you have not designed a bench, you have designed a skate feature. It doesn’t matter what you think you are designing, it matters how people use it.

I hope you find this to be liberating. If you are struggling with a doorknob, or a toaster, or a sound system or your car’s windshield wipers, it is not your fault, it is just bad design. Bask in this insight while you scroll through Gracen Johnson’s sad collection of design failures, #PlacesIDontWantToSit.

So collect the data, and compare it to your Theory of Change. Did it work, or is your theory garbage? If it is garbage, it is a relief you only made a small bet.

4. Repeat.

“Good designers have to ask lots of careful questions, but observing behavior is critical. You can ask people what route they walk, but when you observe the paths worn through the grass, you have real data.”

Collect data and observe the results, because it is a drag to keep repeating the same mistake over and over again. Watch what works, and repeat that.

Now, in this list, consultation just disappears, and I think that is a bit hasty. I think the design experts should humbly observe where the community is struggling—but where do you start observing?

This is when you ask the experts. Consultation can map hot spots. Consultation can prioritize which hot spots to address first. If you need to know how it feels to live in a city, where the friction points are, and what is most beloved and cherished, residents are the only experts. Design a consultation to harvest their expertise, and then act on what they give you.

Consultation is a very small part of the overall process, but can be useful and important.

We need to be more aware of different kinds of expertise, and who has it. Each expert—engineer, resident, or designer—only specializes in a narrow field, and we mustn’t ask them to do each other’s jobs.

Otherwise, we disrespect everybody involved, and we corrode goodwill and trust on all sides.

(Top image source: Mint Chip Designs via Pixabay.com. Creative Commons license.)

About the Author

Ruben Anderson consults on behavior change, sustainability and regenerative systems. He taught Sustainable Design at the Emily Carr University, and won an award for Cradle-to-Cradle product design from the Cascadia Green Building Council. Ruben advised on future-proofed, locally resilient systems while working in the City of Vancouver’s Sustainability Group and with the Planning Department, and supervised a Zero Waste proposal for the 2010 Winter Olympics. He has also consulted for BC Housing, Industry Canada, private sector and NGO clients. He has blogged for TreeHugger.com and theTyee.ca, and presents about behavior change and how Compassionate Systems can increase the effectiveness of pro-environmental behaviors. His recent writing and presentations can be found at www.SmallAndDeliciousLife.com.