A Town Well Planned: Hierarchical Zoning

This article is part of a series in which Strong Towns member and contributor Alexander Dukes proposes a design concept for redeveloping a neighborhood in his college town of Auburn, AL. We hope it serves as valuable inspiration when thinking about design options for your own neighborhood.

Read previous articles in this series:

A mix of uses on Main Street in Ashland, Ohio. (Source: LI1324)

The first article in my “A Town Well Planned” series proposed a three-part regulatory system for managing the design of urban environments. The series refers to this system as the “Civic Development System,” or “CDS” for short. The three pillars of this regulatory system are: (1) The Master Street Plan, (2) Basic Land Use Zoning Plans, and (3) Form Plans. This article is the first of two that will describe the Zoning Plans pillar of the Civic Development System.

The concept of land use zoning is intended to prevent the various land uses from interfering with one another. There are three factors that determine whether a particular use of land is going to be harmonious and inoffensive to the public’s sensibilities: (1) The land use type, (2) the intensity of that land use, and (3) the geographic context of that land use. This article will focus on land use types and intensity. Next month’s article will geographically apply the factors of land use type and intensity to the Auburn Mall site.

Land Use Types

There are four principal types of land use: Residential, Office, Merchant, and Industrial/Utility. Residential land uses are primarily dedicated to homes and the domestic life of the public. Office land uses are leveraged for the production of services that are of a highly skilled or clerical nature. Merchant land uses are reserved for the selling and purchase of goods and services. Industrial and Utility land uses are those that require the generation of nuisances like smoke, noise, or excessive traffic.

The defining characteristic of land use types is their flexibility. Districts that are zoned residential are the least flexible because they cater to those that desire an environment designed for domestic (and in most of the United States, a semi-bucolic) life. Industrial land uses are the most flexible because people are generally unconcerned with the activities that occur in industrial areas as long as they're not interfering with the rest of the city or harming the environment. Because residential districts are so inflexible, industrial land uses should not be placed within them. The noise, shipping traffic, and odor of many industries will harm homeowners’ enjoyment of their residential land. The residential land district is therefore harmed by the presence of industrial land uses.

However, this is not true of the inverse. If a person chooses to build a house within a light industrial zoning district, there is no harm the home can do to the adjacent industrial land uses. In fact, both the resident and the employer gain from this arrangement: The employee gains a shorter commute to work, and the employer gains a better-rested and productive worker.

Unfortunately, contemporary single-use zoning (aka “Euclidean” zoning) does not allow residential land uses within industrial zoning districts. This is due to its strict segregation of each land use type. This article will demonstrate how a hierarchical zoning paradigm can address this critical failure.

To allow less flexible land uses within districts zoned for more flexible uses, zoning codes should develop a flexibility hierarchy. Such a hierarchical model is displayed below, using the aforementioned four types of land uses:

As the model’s arrow implies, any less flexible land use can exist within the more flexible districts above it. For instance, office land uses can occur in districts zoned office, merchant, or industrial. Office land uses may not occur in areas that are zoned residential, because residential land uses are less flexible than office land uses.

This hierarchical zoning paradigm also allows for the easy mixing of uses. If the owner of a small blacksmith shop wants to build a house above their workshop, this zoning paradigm allows him or her to do so. Using a system based on hierarchies affords the public more freedom to maximize the use of their land, which should be the aim of both landowners and the municipality.

Land Use Intensities

Land use intensities are related to the amount and type of activity a parcel hosts. Ensuring compatibility between land use intensities is just as important as ensuring compatibility between land use types. For example, most people don’t want to live in a cozy suburban house across the street from a supermarket. The persistent traffic and sterile aesthetics of the typical supermarket environment would harm the coziness of the residents’ house. Therefore, cities tend to put some distance between supermarkets and suburban homes. However, the residents of a six-story apartment complex might appreciate being across the street from supermarkets. The intensity of the supermarket’s land use is more compatible with the intensity of the apartment complex.

As it was with land use types, more intense land uses should accommodate less intense land uses by right. A model of an intensity hierarchy is displayed below. For the purposes of the Auburn Mall (our case study for this series of articles), four levels of intensity will be used. Additional levels of intensity can and should be added for larger cities.

With this hierarchical model of land use intensity, the four land use types can be given their own measure of intensity. For residential and office land use types, land use intensity levels are inherently tied to the number of people using a space. Intensity levels for mercantile land uses are tied to the “gross commercial floor area” associated with the structure(s) on the lot. For light industrial land uses, intensity levels are mainly related to the amount of noise, noxious exhaust, and public safety hazards generated on a particular industrial site.

To determine what constitutes a “level,” some delineation of each land use type’s intensity levels must be prepared. Delineations for the different intensities of land use types are shown in the chart below.

All structures remain subject to the city’s fire code. Individual residential structures used to house 6 or more persons on a single floor are subject to city safety review. An “industrial & utility” land use shall be classified as the highest intensity that meets any one of its relevant measures.

For reference regarding commercial floor area footage sizes, the average McDonalds is 4000 square feet, while the average Five Guys and Chipotle are between 2,000 and 3,000 square feet. [Source: Auction.com]

The land use intensity and type models and table provide developers a means to determine whether the specific land use they seek to apply to a parcel is allowed. However, it may be conceptually difficult to apply the land use type and land use intensity factors concurrently. Developers would have to flip between pages of the zoning code to determine exactly where their proposed development fits. To remedy this, there should be a land use zoning matrix to simplify zoning code lookups to a single page. Enter the zoning matrix.

The Zoning Matrix

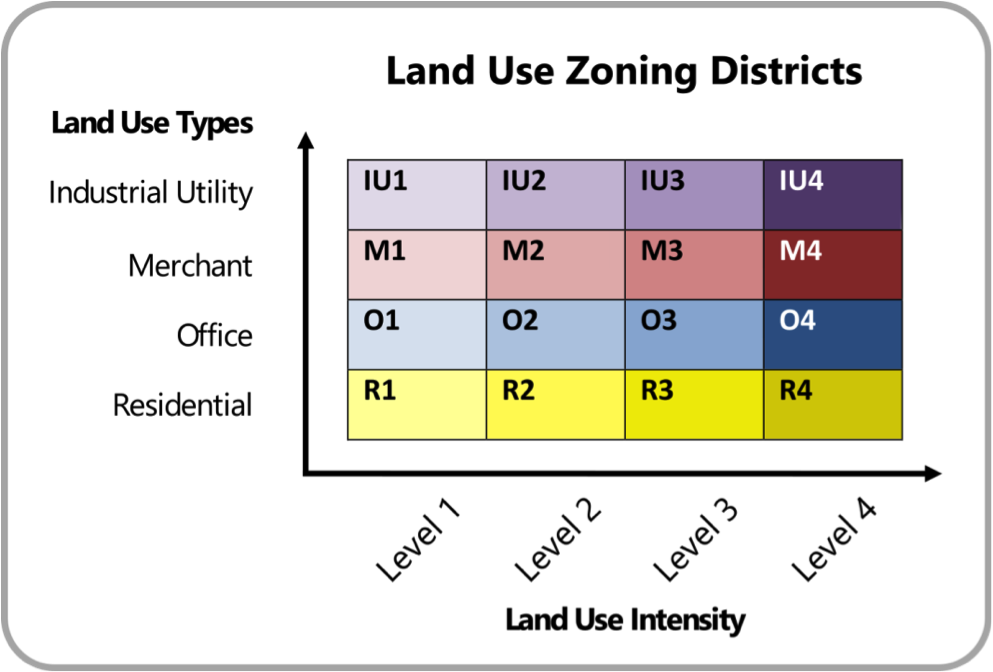

By using land use type hierarchy as a y-axis and land use intensity hierarchy as an x axis, a two dimensional zoning matrix can be formed. The matrix allows a municipality to visually illustrate the concept of the land use hierarchies in a way that can be easily understood by both the general public and seasoned developers.

Developers would use the matrix to determine where they are allowed to build their proposed developments. This would occur in a two-step process: First, developers would use the land use intensity table to determine the type and intensity of their proposed development. Next, the developer would use the matrix to determine which zoning districts can accommodate their development. Four examples below demonstrate this process.

In Example 1, a developer seeks to construct an “R1,” or “Residential – Level 1” land use—for example, a small single-family home. The R1 land use can be within any land use district. Effectively, the developer has no restrictions with respect to where they can construct an R1 class home.

However, Example 2 indicates that a developer is seeking to construct an “IU4,” or “Industrial Utility – Level 4” land use like a large factory. Unfortunately, a level 4 industrial land use can only be built in the IU4 district. Industrial land uses of this intensity must be isolated to unique industrial zones to protect property values and public safety.

Example 3 presents an interesting situation where a developer seeks to build an “M2” land use such as a midsize clothing store. Being in the middle of the land use matrix, the developer has some ability to “move” to other zoning districts, but not the freedom to select any zone they desire. This illustrates how developers can only move upward and rightward from their development’s zone within the matrix. Moving to the left or downward is prohibited because those movements would violate the concept of the land use hierarchies.

Example 4 demonstrates how the land use hierarchies interact with one another. Because the “R4” land use—for example, a large condo building—is the ultimate residential land use, the developer cannot move down the intensity hierarchy within the matrix. But, the developer can move up the type hierarchy, to build an R4 land use in an O4, M4, or IU4 zoning district.

Conclusion

The hierarchical zoning codes’ ability to expand the public’s liberty to build what they want, where they want will improve the health of the land market in municipalities. The ability to combine residential land uses with office, work, or mercantile uses will inevitably drive down the cost of housing and allow entrepreneurs to mitigate their risks with live-work arrangements.

With a more flexible zoning code that recognizes the hierarchies inherent in land use types and intensities, cities can overcome many of the problems inherent in single-use zoning. Developers should only be constrained in their ability to develop land uses when their choice of land use harms others in the zoning district. By adopting a hierarchical zoning code, we can cast off many of the single-use zoning proclivities that have held our municipalities back.

Next month’s article in this series will geographically apply this hierarchical zoning code to the Auburn Mall site.

Read the next article in this series, "Zoning with Context."

(Top image source: Urząd Miejski w Trzebiatowie)

Alexander Dukes (Twitter | LinkedIn) has been a regular contributor for Strong Towns since 2016, and works as a Community Planner for the US Air Force in California. He is a graduate of Tuskegee University and Auburn University, with a Bachelor’s in Political Science and Master’s degrees in Community Planning and Public Administration. With this background, Alexander focuses his planning work on public policy and urban design for both military and civilian applications. Alexander's goal is to build sustainable human environments that provide all citizens with access to cohesive communities, affordable housing, meaningful employment, and beautiful places.