Beginnings, Middles, and Ends

I was recently invited to give a talk at a housing conference down in Los Angeles. Once again my fellow speakers engaged in the usual arguments. Aging Baby Boomers asserted that we need to keep building more 1957 style suburban homes on the edge of the metroplex because that’s what people want and can afford, particularly once they marry and have children. Then a group of Millennials sang their sad song of high prices and a lack of options in the places they really want to live. Each side fortified their argument with statistics contradicting the other side.

As a GenXer (the thin layer of mayonnaise in a giant demographic sandwich) I came at things from a different perspective. Of course the old guys like things the way they are. Of course young people are impatient with the old order. History has a rhythm that plays out in long slow generational cycles. I explored the past incarnations of this pattern in my presentation to make a point. Everything has a beginning, a middle, and an end. The implication is obvious for anyone who’s paying attention. Things are going to change in unexpected ways, and the current debate will become increasingly irrelevant. I raided my vault of photos to demonstrate what this rhythm looks like on the ground.

There were decades in the mid 1800s when American society was incapable of agreeing about anything. We were divided by geography, culture, economics, race, class, and our underlying philosophical visions of how things should be. Our collective dysfunction made it impossible to address long festering structural problems. Once the Confederate States seceded from the Union in 1861, the resulting Civil War broke the gridlock—at great cost in blood and treasure.

But the crisis unleashed tremendous new opportunities and powerful institutions. The Homestead Act of 1862 provided a legal mechanism for ordinary people to acquire and cultivate free land. The Morrill Act of 1862 established land grant universities across the country including Cornell, M.I.T., Tuskegee, and state universities that elevated the skill levels of millions of Americans. The Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 facilitated transportation and communication infrastructure that massively increased efficiency and wealth and unified the expanding nation.

But everything has a beginning, a middle, and an end. After decades of rapid rural population growth and relative prosperity circumstances conspired to dismantle small family farms. The mechanization of agriculture, the rise of industrial cities, boom and bust economic cycles, and the deployment of young people during the First and Second World Wars all gradually depopulated the countryside. The final nail in the coffin struck when U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz radically altered federal policy in the early 1970s toward heavily subsidize large scale vertically integrated corporate agribusiness. “Get big, or get out.” Commodity crops are now cheaper and more plentiful than ever as a result, but much of what was left of the rural landscape was eviscerated.

As the cycle unfolded, the beneficiaries of change were big industrial cities. From 1900 to 1950, Detroit, like so many other cities of its kind, grew and grew and grew—in population, wealth, technological advancement, and cultural importance. Detroit was one of the magnet cities that pulled in rural farmers and international immigrants alike for decades. Good paying manufacturing jobs were the engine that drove Detroit forward. Innovation from private industry, federal policy such as the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, and the massive federal expenditures in production during World War II all fed a specific type of city. Detroit was second to none.

But everything has a beginning, a middle, and an end. Detroit peaked at two million fairly prosperous inhabitants seventy years ago. It has since lost more than 60% of its population and much of its territory is now reverting to nature. The trajectory of industrial cities took a sharp downward turn beginning in the 1960s, as new policies were enacted and society once again moved in a different direction. Long-festering racial conflicts exploded and were never resolved. Corporate management and labor unions fought each other rather than cooperate, so both lost ground in the face of foreign competition. A lack of economic diversification meant fewer alternatives to fall back on. The cumulative consequences of industrial pollution asserted themselves. Crime became a serious problem. Property values dropped while taxes rose and municipal services eroded. Detroit became the poster child for Rust Belt failure and abandonment, but it was by no means alone in its decline. Young people today seem unaware that New York, San Francisco, Philadelphia, Washington D.C., and Chicago were nearly as bad off as Detroit in the 1970s.

As downtowns all across the country began to fail in the mid twentieth century, newly built suburbs were thriving. It was easier to create new places than fix what was wrong with the old ones. A whole host of federal legislation, such as the National Housing Act of 1934, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, and the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, provided the government subsidies and legal mechanisms that promoted suburban development. And for the last several decades, these places have been the economic, cultural, and political center of American life. It’s the only landscape many people have ever known.

But everything has a beginning, a middle, and an end. Suburbia is aging, and the older the cul-de-sacs and strip malls become, the harder it is for local governments to balance stagnant revenue with the ever-increasing maintenance burden of all the attenuated infrastructure. Taxes are rising, municipal services are declining, and the legacy costs of pension obligations and previous promises are simply not going to be honored over the long haul. Most older suburbs are now wholly dependent on outside financial assistance from state and federal agencies. They can’t afford to upgrade their ailing sewerage treatment plants or repave their roads.

Have you seen the state budgets lately? Have you seen the federal budget? It’s not pretty. Sooner or later, the locals are going to be thrown back on their own resources and it won’t end well. The cavalcade of defunct video rental stores, dead Waffle Houses, and abandoned muffler shops represent the failing economic and cultural prospects of places not worth caring about. Once wealthier people start migrating away and property values drop, a vicious downward spiral begins. History suggests that Americans aren’t going to fix what’s wrong with these suburbs any more than we addressed what was eating away at our rural farm towns or industrial cities.

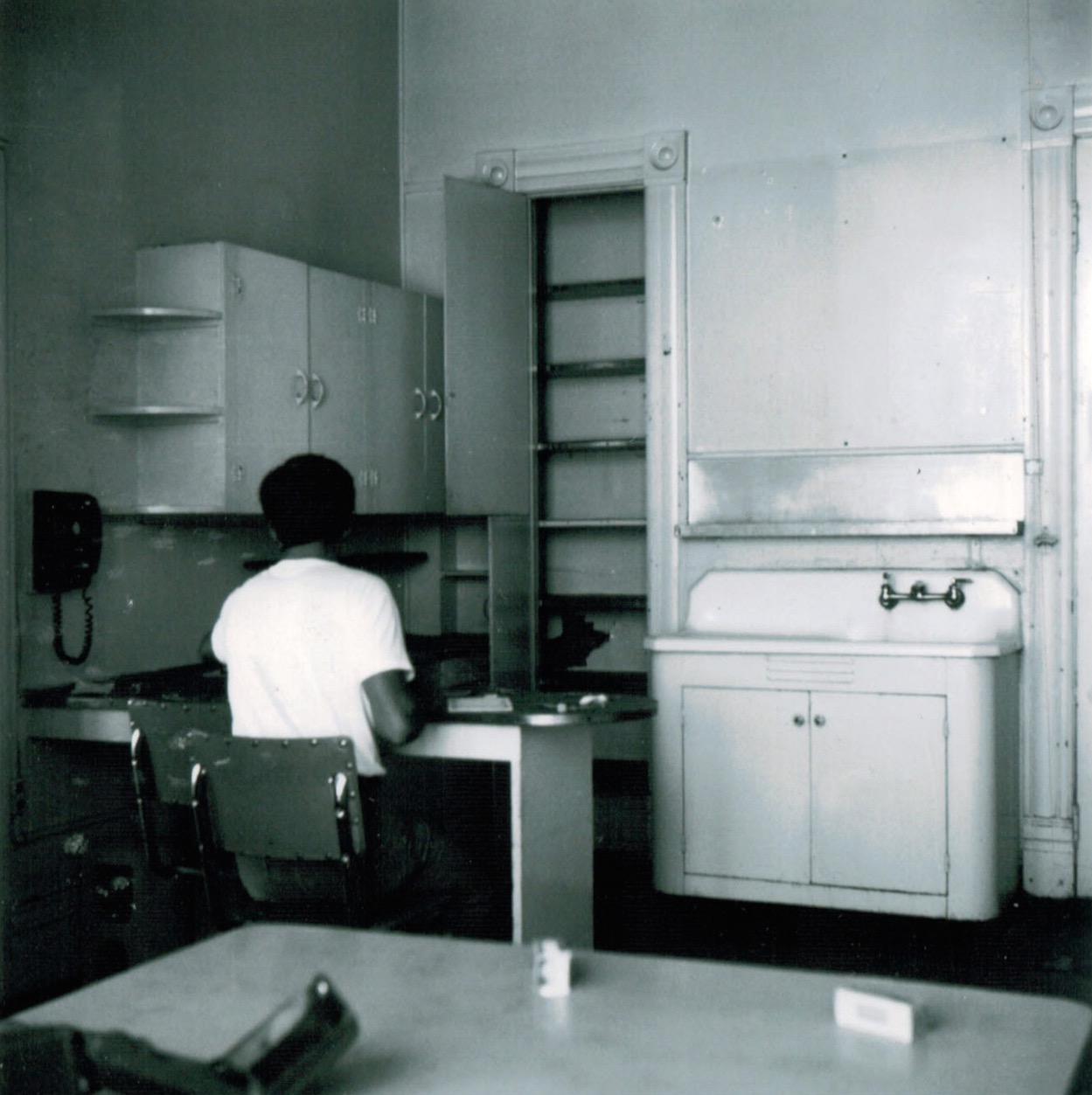

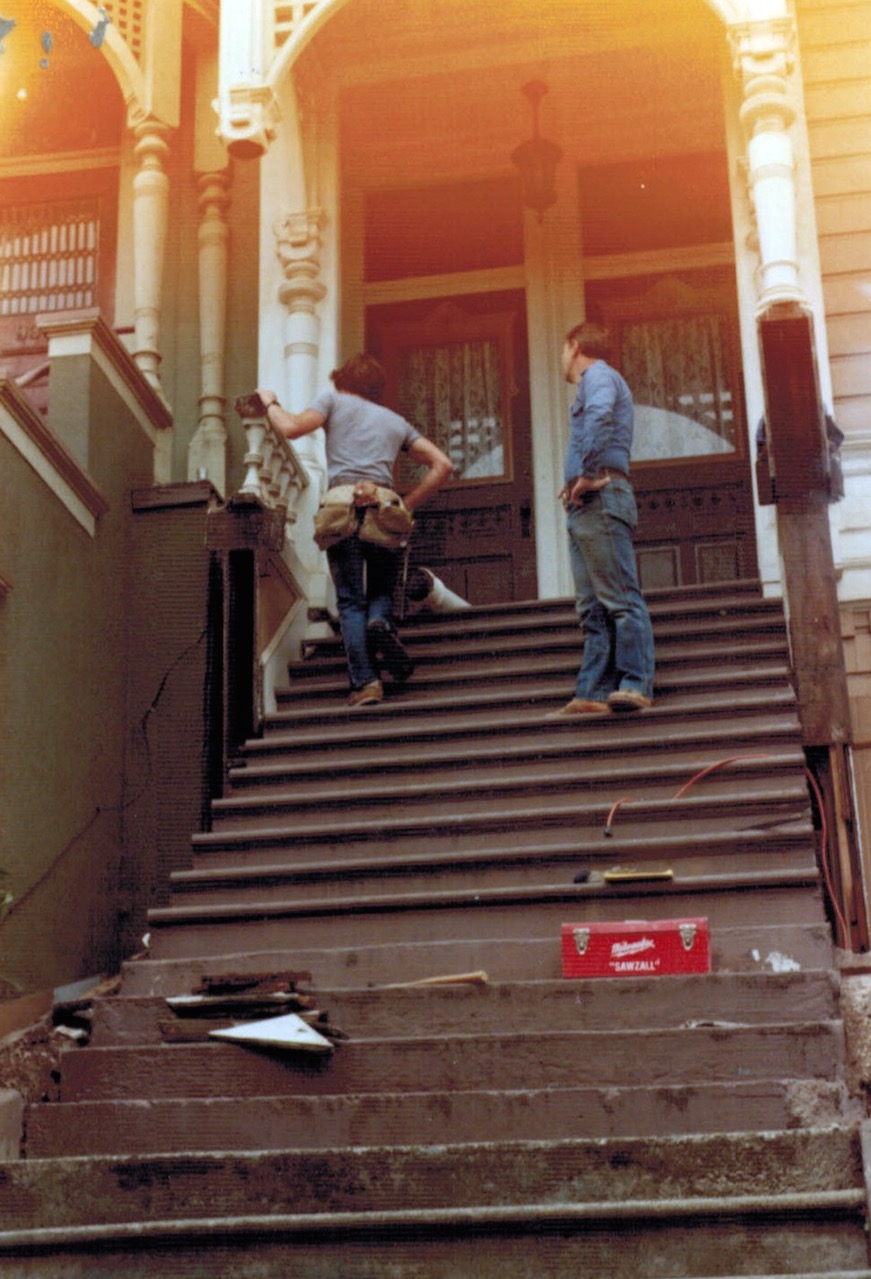

In my presentation I pointed out that sometimes the end of one thing is the beginning of something else. San Francisco, like virtually all American cities and older towns, had hit bottom in the early 1970s as the middle class decamped to suburbia. Property values were low, crime was a problem, and it was self evident to the majority of the nation that inner cities were terrible places to live with no future.

That’s not to say there weren’t pockets of residual prosperity in the best neighborhoods, but the larger trend was overwhelmingly down. But that vacuum created a fertile landscape for reinvention for a small minority to establish a foothold and begin the process of creating an entirely new vision for the old city. New technology, whole new industries, and a completely different culture emerged over time. San Francisco is still regarded as an anomaly by the rest of the country, but now instead of being regarded as too weird and poor, it’s considered too weird and rich. My expectation is that San Francisco is currently choking on its own success and will enter a new period of gradual decline. Everything has a beginning, a middle, and an end.

I finished my talk with the assertion that our current institutions are in the process of failing and are unlikely to be reformed. Instead, our existing set of arrangements is simply going to crash. That’s been the historical pattern. Once the dust settles, we’ll create new institutions and a fresh cultural consensus that respond to pressing needs on the ground. A new generation of young people will be asked to do the heavy lifting during the next crisis, and they’ll be preferentially rewarded for their efforts by the new system. No one knows exactly what that will look like yet. A great deal depends on the nature of the crisis and the ways in which we all decide to respond. Time will tell.

(All photos by Johnny Sanphillippo.)

The Suburban Experiment is a bad business model, and nothing demonstrates that more clearly than Jackson, Mississippi’s, ongoing water crisis.