Revenge of the Strip Mall

The strip mall, in American culture, is more often than anything else an object of derision. It’s an icon of chintzy postwar suburbia and the throwaway culture it nurtured. Strip malls are often described as ugly, tacky, devoid of culture or character or charm. And they’re the flagship native species of a certain type of place: usually, today, a place that has long departed the growth phase of the Growth Ponzi Scheme and found itself sliding downhill into physical deterioration and economic stagnation.

Is it weird, then, that lately I’m finding myself bullish on the unsung strip mall?

A Study in Contrasts: Strip Mall vs. Indoor Mall

There’s a natural study in contrasts, an A/B test if you will, on the southern edge of my city that will help me explain why. An aging strip mall sits across the road from an aging conventional, indoor shopping mall. And there’s no question in my mind which type of building has a brighter future in our struggling suburbs.

Let’s start with a little slide show tour of the strip mall and some of its perhaps surprising virtues:

This strip mall is home to a remarkably diverse and lively collection of businesses, virtually all of them locally owned. It’s able to attract a healthy clientele at all hours of the day and days of the week; the parking lot is usually fairly full. The tenants include restaurants, an ice cream parlor, and a bar; shoe repair, a locksmith, and an old-timey barber shop; salons, furniture, and health stores, and an entertainingly bizarre survivalist outfitter-slash-tattoo parlor. If the American dream of the mom-and-pop entrepreneur is still alive, it’s alive in places that look like this.

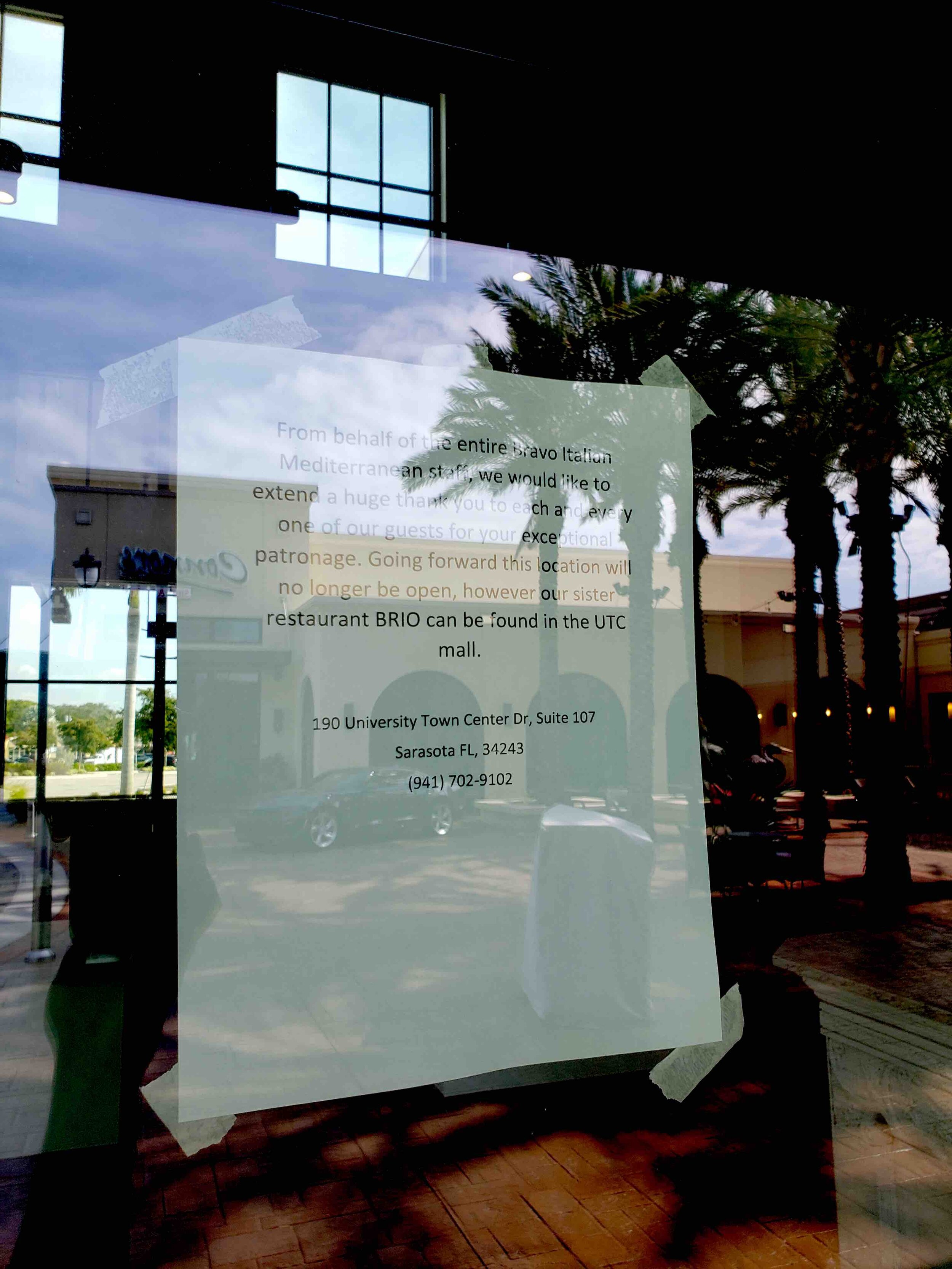

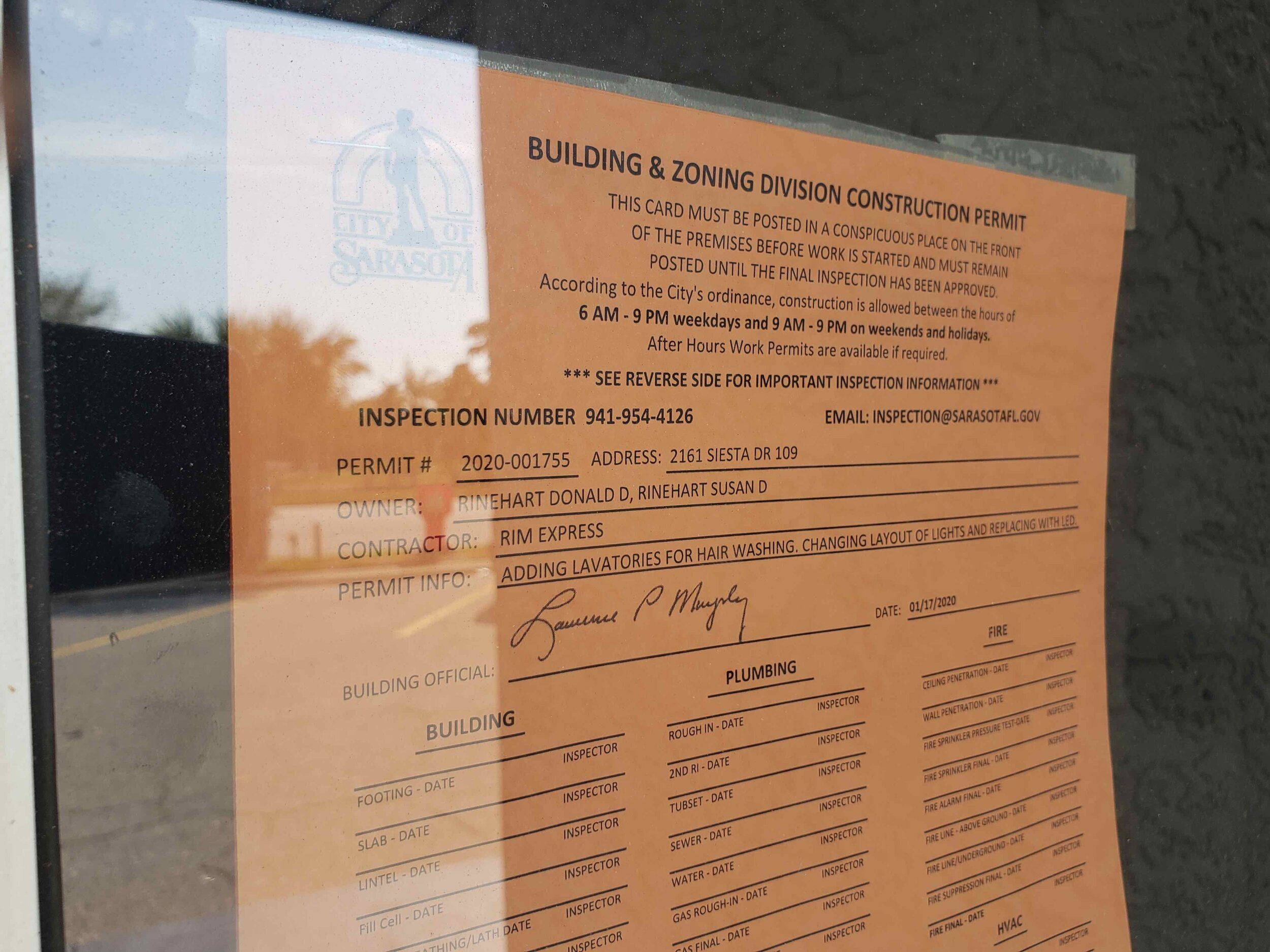

Now let’s cross the stroad and look at the indoor mall. This mall, for a bit of history, is older and closer to the heart of town than the other two large shopping malls in Sarasota. When the brand new UTC Mall opened a few miles away in 2014 (the only new enclosed shopping mall in the entire U.S. in a more than five-year period), the owner of this one—the international mall conglomerate Westfield—saw the writing on the wall and moved quickly to rebrand the mall and diversify its offerings, adding restaurants, a grocery store, and a movie theater. Westfield are the undisputed pros at running this kind of place: if anybody could turn the Southgate Mall around quickly it was going to be Westfield. Their efforts are on display in the slide show below:

Look at the dramatic contrast in the amount of overhead expense. The bells and whistles Westfield has deployed—a bubbling fountain, fancy chandeliers, copious artwork, a fancy bricked entrance with valet station—are not frivolous expenses on the part of the mall’s savvy international operator. They are business expenses, and their function is to prevent the appearance of decline. And for good reason.

A mall is a fragile environment. When one dies, it usually dies in a death spiral: vacancies mean reduced revenue for the operator and reduced traffic to the mall. Since none of the shops are visible from outside, or easy to pop in and out of, the ensemble needs to succeed for any of it to succeed. It’s why malls usually flouder after they lose their anchor tenant (a department store, most often). The spiral of fewer customers and less revenue, in its later stages, can lead to cutbacks in maintenance and in the ability to draw high-rent tenants.

The plan to diversify the Westfield Siesta Key mall’s clientele by adding entertainment and dining options has been a mixed bag. Two of three restaurant spaces appear to be vacant. The grocery store, there for only about a year, recently vacated its large space. Cinebistro is doing well but has its own entrance and doesn’t really do much to prop up the rest of the mall. The overriding impression is of a savvy owner with deep pockets doing everything it can to prevent the Siesta Key mall from slipping into decline, and yet it may well not be enough.

The potential upside here is very low. What do you do to salvage this place, besides what they’re already doing?!

Why does a strip mall not go into the same death spiral as an enclosed mall when businesses start to close? Three reasons:

Granularity: the individual spaces are small, adaptable, and easily filled.

Mutual idependence of the retail spaces: Because the strip mall’s individual businesses open to the street, the success of one is not overly dependent on the success of its neighbors.

Low Overhead: The mall’s tenants pay substantial fees to keep the lights and power on in the corridors, the fountain bubbling, and the artwork maintained. None of that is true in a bare-bones strip mall.

On the flip side, look at the potential future upside for that strip mall, if the city decides to recognize it as the asset it is and put some resources into its success. The strip mall is not pretty, and its environs are an ocean of asphalt. But how large is the functional gap between it and a traditional downtown main street, really?

The list of small-bet things that could be done to spruce up the strip mall is long. Plant some trees. Remove some of that front parking and (with the city’s cooperation) replace it with on-street parking on this vastly-too-wide street; use the space for expanded sidewalks, landscaping and cafe seating.

This could become a pretty great place with a little imagination.

The enclosed mall, barring complete gutting and redevelopment of the structure, is pretty much always going to have the fundamental fragility of a mall: high overhead and a dependence on successful anchors. Development might be possible on its parking lots, including some housing, but not much can happen here that would be a small, experimental bet. There’s just huge downside and very, very little upside.

Strip malls have some significant problems that aren’t going to go away. Most were built to be auto-oriented with a parking lot in front—a problematic design for encouraging a walkable environment—and there’s sometimes not a good alternative place to put still-necessary parking. Many are in stroad environments that act as a huge barrier to people getting around safely and exploring the area. Often the buildings themselves are of low quality and have structural problems as they age.

All that aside, strip malls serve an important and growing niche in our society. There’s a reason strip malls are associated—in places as diverse as Maryland, Georgia, and California—with upstart immigrant businesses. They’re just about the lowest bar to entry there is besides a truck or pop-up stall for an entrepreneur with a dream.

When Jane Jacobs wrote 60 years ago that new ideas need old buildings, these absolutely were not the old buildings she was thinking of. But today, just maybe, they are. And there are some lessons in them we shouldn’t ignore.