Movie Set Urbanism: Revisited

Countercultural backlashes have a way of being subsumed into the dominant culture and marketed to a new generation of consumers as just another lifestyle fad. In the process, they’re stripped of any of their subversive intent. Think of hippie fashions on sale at the mall to 1990s teenagers—the actual hippies’ kids.

New Urbanism has suffered some of this fate. The movement, which began in the 1980s, was a reaction to the failures of the North American suburban experiment. An iconoclastic set of architects, urban planners, and developers set out (with mixed success) to recapture the elements of a traditional, pre-automobile urban form that led to safe, lively streets; lovable buildings; and a sense of community and place.

Many New Urbanists were and are motivated not by nostalgia or aesthetics, but by serious concern about the very real costs of endless suburban expansion. Today, however, the movement is a victim of its own success. The New Urbanist aesthetic is popular and pervasive, yet the New Urbanist critique has not achieved its transformative mission. In the suburbs of any major city in America, you can find developers marketing "downtown living” and urban chic in new mega-developments that resemble a century-old small town main street…as long as you don’t turn and face the wrong direction.

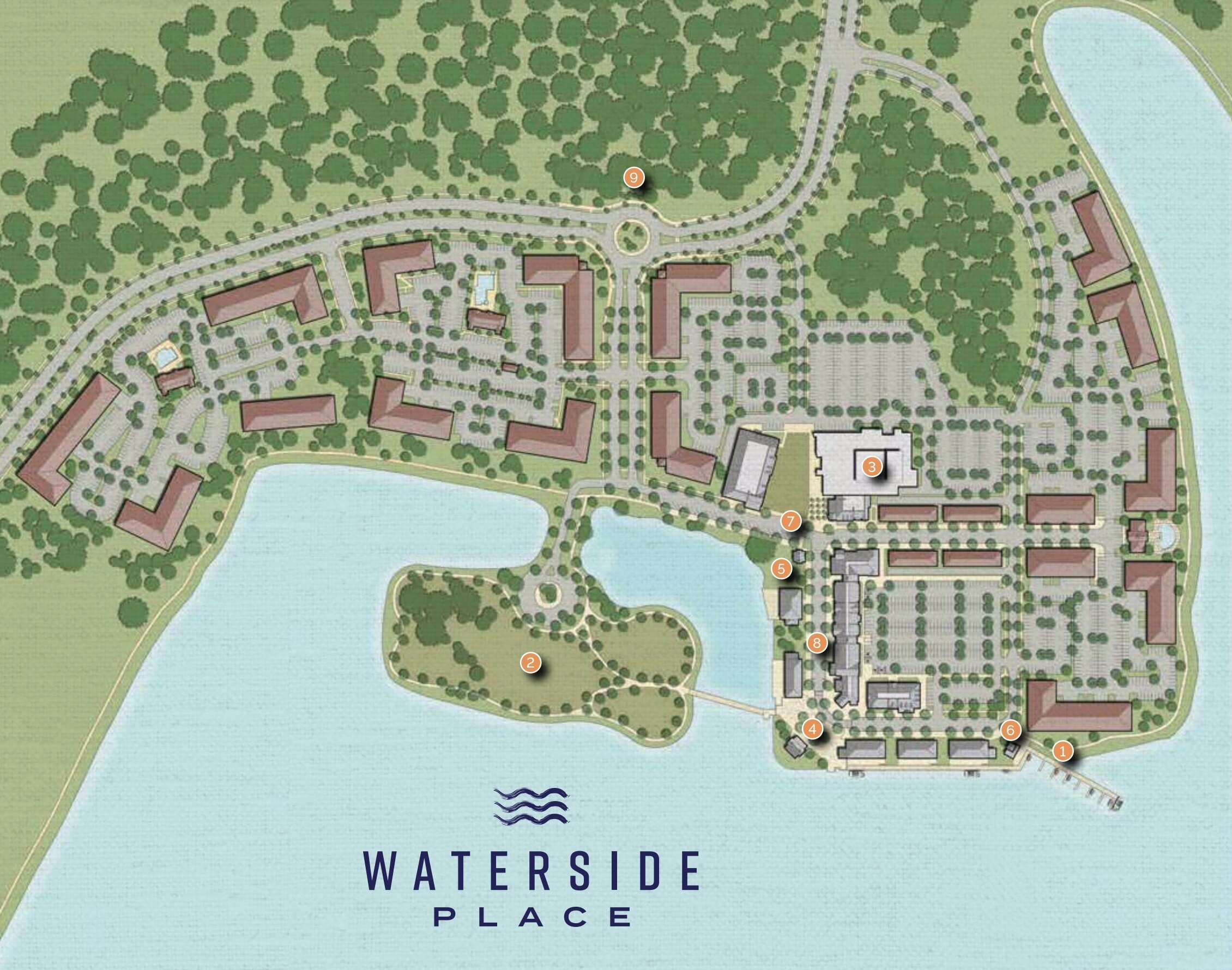

I wrote about one of these places—Waterside Place at Lakewood Ranch, Florida—in a 2020 piece called "The Rise of Movie Set Urbanism." You know, those rows of fake building façades with nothing behind them that you see on a movie set, like for an old Western? They’re, of course, carefully shot from a limited range of angles during film production to disguise the fact that these places are all hat and no cattle.

In reality, these developments are islands of faux-urbanity which you have to drive to and from, functionally no different than the strip mall and the subdivision. And the proof lies in the oceans of parking that inevitably accompany them. With so much land devoted to cars (getting them there, parking them once they’re there, and accommodating the stormwater runoff from all that asphalt), Waterside Place is doomed to be an island. It’s a facsimile of a downtown, which advertises itself as a downtown, but there’s no town—and no path provided for a real one to ever grow around it.

I wrote about Waterside Place back when it was just a plan with some renderings, but I've followed the project's development since then. I went out in March 2020, early in Waterside’s construction, to take some photos that capture the industrial scale of the project. I’ve compared suburban development to extractive industry before, half metaphorically, but in this case it was eerie and unexpected to be able to wander right in here on public streets and view something that felt like visiting a giant mining site.

I went back this month (October 2021) and the project has come along dramatically. People are now living in several of the apartment buildings and a row of Main Street townhouses. Signs advertise the national chain retail tenants already lined up.

Yet the phony, John Wayne movie-set aspect is even more evident now than it was in the renderings. You can explore the site on foot to a point. Though certain areas are behind caution tape and "No Trespassing" signs, outside of those I was among a number of people out walking dogs and the like.

From the right angle, the illusion of a pretty high-quality urban environment is convincing. Pleasant, ample, safe sidewalks; storefronts that engage them; traffic-calmed streets. But it’s all one sided. Here’s the front of a row of townhouses…

…and the back:

Here’s the front of the main shopping street:

…and here’s the back:

An apartment complex, from the front…

…and the back:

The key issue here, the overriding factor, is the staggering amount of land devoted to parking. Beyond even those parking lots, though, is a buffer of undeveloped land separating “downtown” Waterside from the adjoining subdivisions. This appears deliberate and not slated to change. Maps depict much of this land as a nature preserve, and the closest residential subdivisions are enclosed pods unto themselves, with only one or two entrances. This is what it looks like to approach Waterside Place from the west:

And as you leave Waterside Place headed north, you drive for nearly a full minute on a fast, wide road before you get to the first residential area—which is a massive subdivision that winds around a lake, meaning only a few of the homes within it are even walking distance from the pictured entrance. Some are as far as another mile away.

I won’t say I’ll never go to Waterside Place for a meal or some Duck Donuts, or even just to stroll along the lake. As a drive-to recreational destination, it looks cute. As a place to live, I would choose it over a gated subdivision any day. But it's not functionally different from regular suburbia. It’s just a rebrand.

This kind of thing, all over the continent, wouldn’t offend me so much if local officials didn’t so often think this was New Urbanism. But it’s not just sold to the public that way; it’s also used by officials to let themselves off the hook for actually reckoning with any of the criticisms of the suburban experiment—from the ecological and climate consequences, to the displacement of rural communities, to the big-box homogenization of retail and associated loss of opportunities for local ownership, to mounting debt and deferred maintenance obligations.

I’ve heard planners and local elected officials alike (in many places, not just here in Sarasota County) boast of being forward thinking, of practicing cutting-edge planning, of rejecting “sprawl,” of embracing "density" and "walkability" because they approved something like Waterside Place. It’s easier to do that than to fundamentally reconsider the way your development code works or the kinds of things it allows. But the latter is what’s actually necessary to build a generation of stronger places.

A collection of historic photos helped this advocate show how urban renewal marred his hometown, and left an inhospitable mess in its wake.