California's SB 9: A Slow Reversion to the Historic Mean

This article was originally published on Strong Towns member Johnny Sanphillippo’s blog, Granola Shotgun. It is shared here with permission. All images for this piece were provided by the author.

Several different friends have asked me about a new land use law here in California. Senate Bill 9 (SB 9) creates a state level administrative mechanism for single-family homes to be restructured into two distinct legal homes as of right. It also allows existing single-family lots to be subdivided into two separate legal parcels. The end result is that an existing property occupied by a plain vanilla suburban home could be reorganized into two unassociated properties, each with two units, for a total of four homes on the same bit of land. As you might expect, the law is controversial.

Supporters of SB 9 expect these rules to facilitate the construction of many new homes, particularly in areas that are already built out and in the most desirable locations close to jobs, culture, and amenities. This increased supply would eventually rebalance the decades-long, pent-up demand and result in more reasonable prices for both owner-occupied homes, as well as rental units. There are some who suggest this would also have beneficial effects on the environment and society as outward development pressure into farmland and nature will be diminished along with corresponding long commutes with the associated pollution, et cetera.

Opponents are up in arms and see this as yet another example of the kind of social engineering that’s destroying America. So-called “stack ‘em, pack ‘em, and track ’em” policies are interpreted as attempts to strip the population of freedom and impose either top-down government control or rentier corporate capitalism—or both. And there’s the old argument that plenty of cheap little homes and crappy apartments will attract the wrong element into otherwise respectable neighborhoods, where such people don’t belong. In terms of the environment, densely populated cities are devoid of nature, polluted, crime ridden, and prone to disease. Only a dispersed suburban or rural living arrangement is considered a tolerable human habitat suitable for democracy, freedom, prosperity, and health. The division between opponents of SB 9 and supporters of it tends to fall, respectively, between the people who already own and inhabit single-family homes and those who don’t. Okay. Hold that thought.

This afternoon I was helping friends move house. They placed an ad on Craigslist offering their old refrigerator to anyone who would take it away. A woman arrived and I carried it out to the sidewalk for her. As I slid the fridge into her Toyota pickup, I looked at her. She was a tiny lady in her mid 60s. The fridge was taller than she was. I asked her how she was going to get the fridge into her house. She waved her hand saying she’d figure it out somehow. So I asked her again. Was there anyone who would help her when she arrived back home? After some back and forth, I offered to travel with her to do the lifting and she agreed. Partly this was my mitzvah for the day. My good deed. And partly she seemed like an interesting character and I was hoping for a glimpse into her world. I was not disappointed.

She lived in a rented two-bedroom apartment. Her unit was on the lower level of a back garden duplex. Out front was the main house which was also a duplex. This property was built over a century ago and is typical of many such homes all over San Francisco. The standard development pattern back then was for a family to buy a vacant plot of land, usually on a cash basis or a short term, interest-only loan with a balloon payment after a few years. The land wasn’t necessarily on a paved road, didn’t always have access to municipal water or sewers, and there was no electricity, natural gas, or telephone connection back then—at least, not at first. Over time the owners would build whatever they could afford; again with either the cash they had on hand or a series of more short term loans. Over a number of years or decades, the property was build up in stages.

The house in the back could have been the original space and the house in front might have come later, or vice versa. And these spaces almost certainly went through a series of permutations over the last hundred years. Both homes might once have been occupied by the same multigenerational extended family, or each structure might have been a single-family home before they were subdivided later on. And sometimes a duplex or fourplex was recombined into a single-family home again. It was also common for businesses of various sorts to occupy the front or rear of many of these homes.

While this incremental construction was underway, all the properties next door and up and down the block were proceeding in a similar fashion. Not everyone liked everything their neighbors did (or neglected to do) but this was all part of the normal established way towns formed and grew. This particular place isn’t exactly compliant with SB 9 specifications, but it comes pretty close to the spirit of the law in many ways. These little mini-cluster buildings were absolutely normal all over the country right up until zoning regulations, building codes, financing mechanisms, and cultural attitudes shifted around the 1950s. Then everything about them became illegal and socially repugnant. Yet here they are, all these decades later still kicking.

The lady was happy to have the free fridge. Her old one was small and had stopped working months ago. She thanked me for installing the replacement in her kitchen and we chatted as she drove me home. She pays $1,400 a month for her two-bedroom apartment and it comes with a parking space in the garage. That might seem like a lot of money in other parts of the world, but it’s a real bargain in San Francisco. She’s happy to have it and knows if she ever had to move out it would probably mean leaving the city altogether, or paying more for a lesser space. Could she live in a better space for a lot less money in rural Kentucky? Absolutely. But she values life where she is, even on her tight budget.

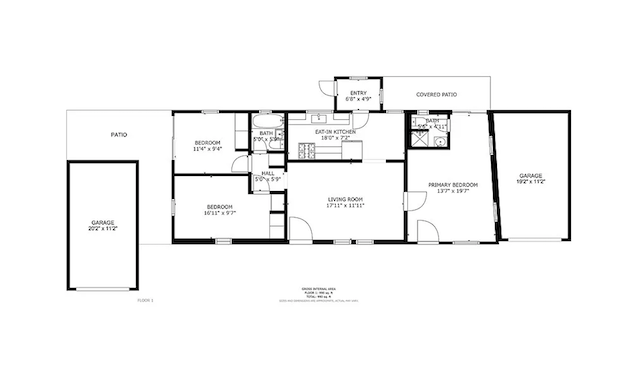

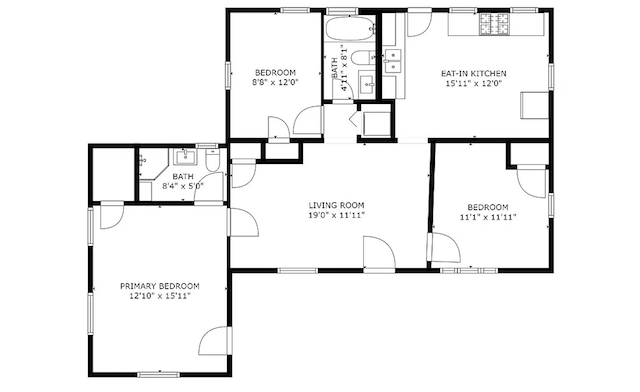

I want to make a point about post-war suburban development. Here are photos of my friend Chris’s home down in Los Angeles. The property was built in 1947. Notice that there are two modest one-story homes sitting on a single lot. This was a normal thing for people to build within living memory. A duplex makes sense for the owner who could occupy one unit while renting the other. In many cases these homes were meant to provide multigenerational housing for extended family. Chris couldn’t have afforded to buy this property if he didn’t have the rental income from the second unit to offset a significant portion of his mortgage. His tenant couldn’t have afforded to rent her unit in this location if it were a single-family home with a larger garden.

Also notice that each home clearly began as a two bed–one bath and each was modified at some later date to become a three bed–two bath by converting garage space into living space. This also was completely normal for decades. Properties were routinely altered to fit the changing needs of the occupants. Over time, new laws were introduced to restrict such modifications, or to make them far more onerous and expensive.

That was the whole point of exclusionary zoning and building codes that mandate particular outcomes. The relentless insistence on single-family homes is a relatively recent development. These rules were cultivated specifically in order to make property less attainable. Supply was intentionally restricted in order to drive up prices and filter out people who couldn’t reach that first financial rung. These policies have been highly effective for decades. Four years ago, Chris paid $875,000 for this place. He died a couple of months ago and his family sold the property for just shy of $1,300,000. That kind of rapid asset appreciation has many contributing factors, not all of which have anything to do with zoning regulations. But let’s not pretend there’s a free market in property when the scales are artificially tipped so far in one direction.

SB 9 is an attempt to get back to some small compromised version of the older normal development pattern of small scale, incremental, and adaptable town building. I’ve listened to the arguments for and against and I’ve decided it’s much ado about nothing. There are a limited number of existing properties that lend themselves to this kind of adaptation, given the prevailing rules. They’re mostly older, smaller homes on relatively large lots. Some prosperous homeowners will expand their dwellings to include granny flats and in-law suites to meet their personal needs. I’ve written about this before. But let’s not pretend this is about increasing the housing stock or generating more affordable units.

The bulk of the genuinely affordable housing in places where it’s most needed is being supplied in an ad hoc manner under the radar. In working-class suburban neighborhoods, ordinary single-family homes are quietly retrofitted into de facto multi-family properties. Bunks are offered for short term rental and fill a need in the absence of any other options. Officialdom is aware of the phenomenon and turns a blind eye because our towns and cities can’t function without an army of low-wage workers, and those people need to live somewhere. The key is to contain these accommodations to a designated area in the least desirable part of town with separate school districts and lesser levels of municipal services—then milk them for tax revenue.

The happy medium for middle class sub rosa duplex accommodations has long taken the form of the “craft room.” Property owners who are more or less solvent and otherwise respectable (define as you may) often chose to carve out a section of their existing property and take on a “roommate” for income. Most home owners, as well as renters, prefer their own space and don’t like sharing beyond a certain point. Creating legally segregated spaces is an administrative can of worms and gets very complicated and expensive really fast. But a bed with a private bath and a door out to the garden works pretty well. Add a wet bar, microwave, portable hot plate, and mini fridge, and it’s just a spare room with some plug in appliances. Nobody here but us chickens.

All across the country there are basements, attics, garages, back bedrooms, and garden sheds that have been repurposed as income suites without crossing the invisible cultural lines. This is what’s possible under the present circumstances. The more expensive and scarce housing becomes, the more of this sort of thing emerges. It isn’t enough. It doesn’t work for everyone everywhere, but it’s the best option at the most reasonable price point for both the landlord and renter. I spent much of my youth living in exactly these kinds of spaces, myself.

Now, here’s the fascinating thing I see happening in new developments in expensive parts of the country. This particular spot is three hours east of San Francisco. It’s where grazing cattle bump up against freshly paved roads, shiny new office parks, and fluorescent floodlit strip malls.

Land just about anywhere in California is expensive. On top of the cost of land, there’s the enormous expense of establishing infrastructure to make that land buildable: roads, water and sewer pipes, electricity, natural gas, telecommunication cables, grading, storm water retention ponds… It’s a long list of spendy items that can’t be avoided. In addition to the hard infrastructure, there are the soft costs. Building permits, impact fees, environmental assessment studies, set-asides for parkland and buffer zones, school fees, blah, blah, blah. Add it all up and a standard suburban quarter acre lot is going to cost $1 million before a house is even built on it. The average home buyer can’t absorb that price point, so if a developer expects to sell any homes, there needs to be more units squeezed onto less land. This reality has given rise to the “Platypus.”

Making the homes smaller isn’t really an option. Buyers are looking for three or four bedrooms and two or three baths, with a two car garage. Even if developers thought they could make money selling little 600-square-foot cottages, municipalities have spent decades honing zoning regulations and building codes specifying minimum square footage for new construction. 2,400 square feet (223 square meters) is the norm in many suburbs these days. It’s one of the ways towns filter out the riffraff. If you can’t afford a large home, you don’t belong there. I took these photos a few years ago, so this construction has nothing to do with SB 9. These are straight-up boilerplate condominium complexes trying really hard to look like single-family homes. They’re meant to appeal to buyers who can’t afford a place with a yard.

The scale of these new neighborhoods is quite similar to what can be found in many older parts of San Francisco. The buildings are about the same height and volume and the same distance apart from each other. It’s convergent evolution across time. Unlike construction and finance methods from a century ago, these new developments are built all at once to a finished state and are sold off with thirty year government-backed mortgages. They aren’t expected to ever change. Homeowner association bylaws and municipal regulations are designed to keep everything trapped in amber forever. That doesn’t mean they won’t ever change. It just means that when the change does come, it will be on the sly.

If these homes survive long enough, they might mutate in unexpected ways. A hundred years from now society may have very different ideas about what’s appropriate. These homes are made of compressed dust and thin plastic films. I can’t say I expect them to endure. Time will tell, but I won’t be around to find out.

Here’s another little mini development in another part of the Bay Area an hour and a half north of the city. This may be one of the better examples of how recent market trends and subtle shifts in zoning regulations are taking us Back to the Future.

These new homes are remarkably similar to the old San Francisco row houses, complete with accessory dwelling units above the garages. Did these materialize instead of ranch homes with front lawns and backyards because of some obscure state legislation? Or was it just the relentless push of external economic reality catching up with suburbia?

Just as a fragile ecosystem can wither without the right conditions, our housing system is struggling under the weight of imbalance. But small, intentional shifts can restore stability. The seeds of change are already planted. It’s time to cultivate them.