The Modern Approach to Development Doesn't Work for Local Communities

This article is part two in a new in-depth series we’re launching on the economic challenges facing resource-based communities, and strategies that can help build lasting prosperity. Read part one here and part three here.

Image via Flickr.

A Strong Town is a place that, at a minimum, has the resources and the capacity to maintain its core systems over time, providing the critical services and ongoing maintenance necessary for the community to endure. Places that cannot meet this threshold do not control their own future. Such places require ongoing assistance from the federal and state governments, a rising level of debt and taxation, or a Ponzi scheme-style commitment to growth and expansion, just to maintain essential services. They are fragile, dependent on others for their very survival.

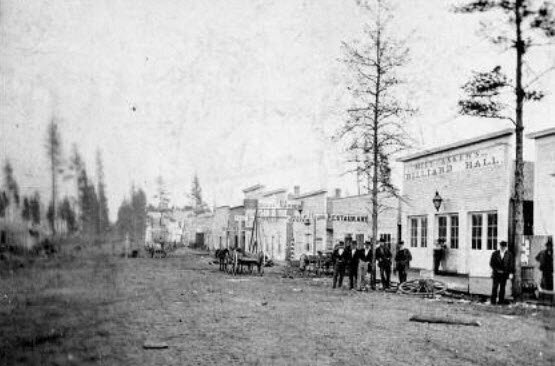

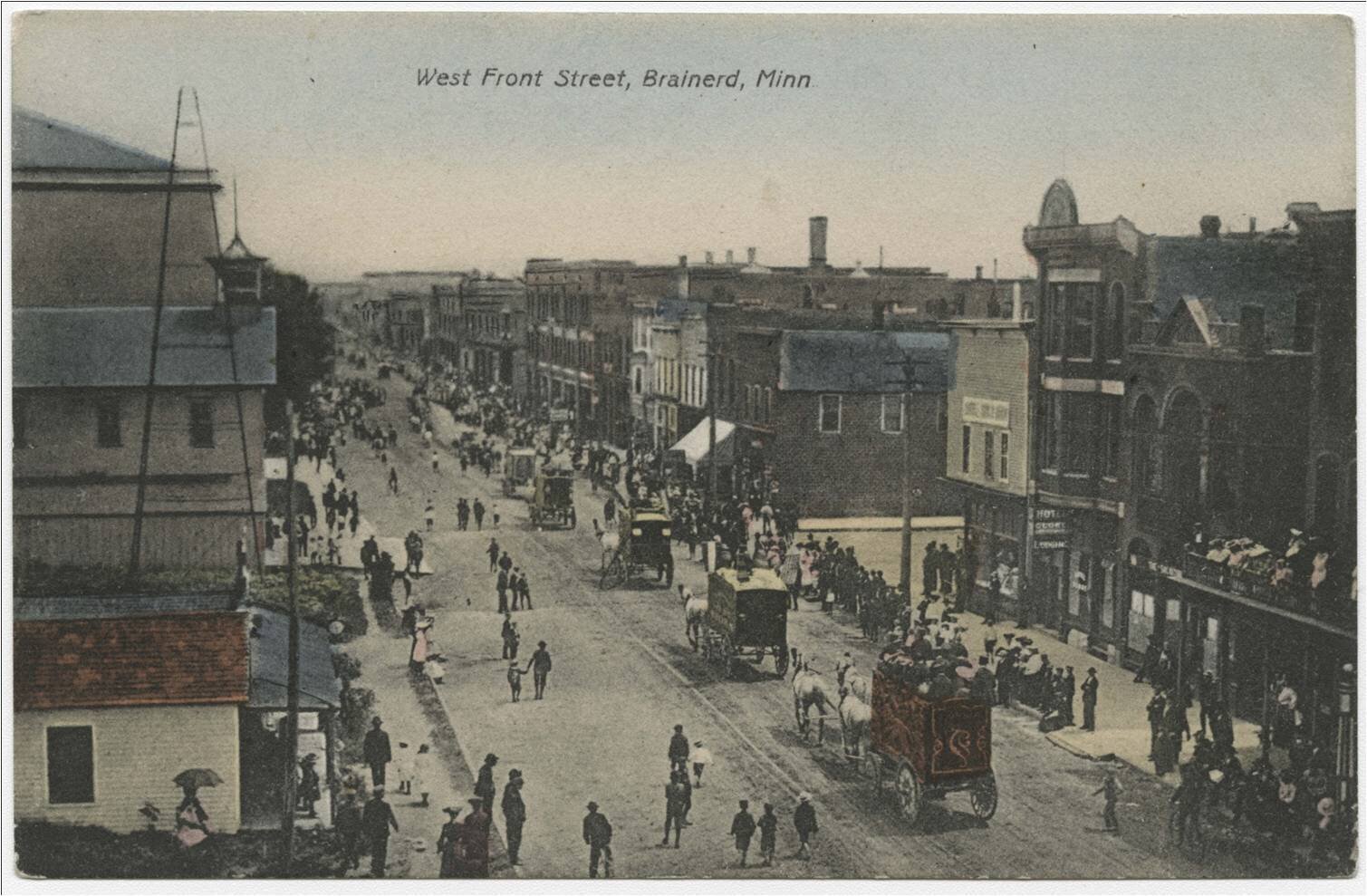

Cities of the past—especially small, remote cities that grew up around the exploitation of natural resources—were Strong Towns. They had to be or they would not have survived; there was nobody coming to bail them out. We can learn a lot by studying these places and the incremental way they grew. The quintessential frontier town was merely a collection of popup shacks assembled along a dirt street. There was very little private investment in them and even less public investment. We can think of this phase as a “little bet,” a small experiment to see whether or not the place would take.

Many cities never got beyond that initial phase; they failed before they really got started. Those that endured, however, all grew in the same way: incrementally. Like a culture in a petri dish, the small city would grow incrementally upward and incrementally outward while the popup shacks were converted into more intense buildings. The process would continue over time, with the city continuing to expand outward while also thickening up within. Rising land values and aging buildings combined to create natural redevelopment pressure that resulted in buildings of even greater intensity, particularly in the core of the city where land values were highest.

Above: Brainerd, Minnesota, in 1870, 1894, and 1930s, incrementally growing up, step by step.

With each step in this cycle, private wealth increases the capacity of the community. That capacity was tapped to improve public services, whether it was paved streets, improved drinking water and sanitation, or better parks. This phasing where private investment came first, and then public investment, is one of the primary features of traditional community development.

A different approach to community development grew out of the experiences of the Great Depression and World War II. To avoid economic downturns, federal and state governments, along with the Federal Reserve, banks, and other financial institutions, add capital to the financial system in order to keep the economy growing. A build-it-and-they-will-come mentality has the public sector (especially at the local level) making initial investments to attract and support subsequent private-sector investment.

Traditional Community Development: Increased private investment supports subsequent increases in public investment.

Modern Community Development: Public investment is used to induce subsequent private investment.

This shift has created tension between what is good for the macro economy and what is best for local communities. The goal at the national level is economic growth, particularly as represented by Gross Domestic Product (GDP), a measurement of transactions in the economy. At the community level, economic growth is positive so long as it doesn’t undermine long-term stability. The key to success for local communities (and in particular those that are resource focused) is building community capacity through wealth creation.

Traditional Community Development: Growing community wealth increases community capacity.

Modern Community Development: Growing economic transactions increases community capacity.

Traditional cities were designed to retain capital, to have the money that entered the community circulate locally and stick around as long as possible before exiting the community. These places would sacrifice absolute growth in order to experience greater wealth creation. That balanced approach provided stability while increasing capacity to undertake collective action.

Think of traditional cities as a bathtub where money is represented by the water. Turn on the faucet and water (money) pours in. Open the drain and water (money) pours out. The simple strategies for a traditional city were to increase the flow from the faucet while decreasing the flow out the drain.

For modern cities responding to the incentives of a transformed economy, it is all about increasing the flow. Macroeconomic policy has focused on making the flow of capital as great as possible while encouraging local communities not to bother about retaining that capital. So long as the flow keeps expanding, the fact that it flows right through and out the drain is immaterial.

The modern approach theoretically works for the national economy, and it might work for a handful of large cities, but it is ultimately ruinous for most local communities.

Working harder just to stay in place is a common experience for Americans, especially those living in resource-focused communities. To become a Strong Town, a city needs to get off this treadmill and get back to work building their local wealth and capacity.

The Strong Towns Approach to Economic Development

To build a prosperous place—one that is improving so that community members experience and anticipate a future they want to be part of—a community needs to focus its energy and resources on strategies that build local wealth. The Strong Towns approach combines five strategies that do just that.

Cities will build stability and prosperity when they are:

Redirecting the flow of capital so that it stays in the community longer, growing local capacity and providing greater community benefits.

Making low-stakes space for entrepreneurs (people in the community with crazy ideas and the passion to run with them) to fail quickly, learn, and get back to innovating.

Accelerating success by aggressively growing enterprises that import capital into the community.

Allowing the community to grow incrementally again, to thicken up and become more productive while shunning the large leaps and silver bullet projects that are a distraction today and a drag on future prosperity.

Reinforcing the Main Street economy that expands the opportunity people have to improve their quality of life, and the lives of those around them, while growing their own financial security and stability.

The strategies in the Strong Towns approach are within the reach of every community to implement, regardless of size or current capacity. They simply require a change in approach, a mental shift in thinking, that redirects existing resources away from unproductive activities to things that produce local wealth and capacity.

A Strong Towns approach is not a quick fix but a commitment to good habits and more intentional decision making. Think of it like diet and exercise for your community’s economic health.

The generational ranch model has been wobbling since WWII, but here's how one small community in Montana is keeping grazing land as working lands, as well as bolstering opportunities for young producers.