Road Diet Seven Years in the Making—Was It Worth Every Minute?

(Source: Bike West Hartford.)

With little fanfare, other than a local blog post and a couple passing mentions, my town of West Hartford, Connecticut, approved a road diet last week, quietly culminating a difficult campaign over seven years to make North Main Street safer for everyone.

There was much trepidation and many manipulations necessary to bring a relatively straightforward, time-tested, idea to completion in this town of 63,000.

In our town, which is in the first ring of streetcar suburbs outside the city of Hartford, North Main connects a retail center and acres of surface parking with the town center. Before the road diet, it consisted of four lanes of arterial traffic routinely traveling 40 to 50 mph, sometimes barely a foot from the sidewalk and front lawns of single-family residences. There were sections of North Main where the sidewalk was literally a utility pole diameter and a curb width away from the travel lanes.

For many years, town residents complained about the speed of travel, frequent crashes, and the difficulty in crossing North Main Street, especially at the American School for the Deaf campus, a midpoint in the 1.8-mile road diet project area.

The public litany included one memorable anecdote from Mayor Shari Cantor, a supporter of the road diet, whose son was ticketed on North Main for driving 50 mph. His defense to his mom was he was traveling the same speed as traffic, she told a meeting last year. Mayor Cantor has been a consistent supporter of the road diet, and she was ultimately joined by two-thirds of residents who answered a large survey.

When I first moved here two years ago, I discovered the river of near-highway-speed traffic on North Main a few blocks from our quiet neighborhood street, and I couldn’t believe it was tolerated by the community. As it turns out, it wasn’t.

The prescription offered and delivered was for a road diet, a change in lane alignment usually only needing paint (lane striping) to transform four travel lanes (two in each direction) to two travel lanes with a center left-turn lane. Road diets are promoted as cost-effective solutions to addressing speeding and crashes on arterials and stroads.

Pre-road diet alignment of lanes on North Main Street. (Source: Google Maps.)

In West Hartford, the process might have been more cost effective, but the town found difficult headwinds from a vocal core of residents.

Originally, there was a campaign by local advocates in 2015 which resulted in a $75,000 feasibility study funded by the regional transportation planning organization. It recommended a road diet and several more costly interventions, including new trail construction that needed right-of-way acquisitions.

The town manager at the time wasn’t ready to move ahead with the proposal, but a successor responded to public advocacy—particularly by one resident leader named MaryEllen Thibodeau, who did amazing work to organize neighbors and spearhead support for the road diet. Sadly, she passed away in November 2020 before seeing the project finalized.

North Main re-striped with two travel lanes and a center turn lane. (Source: Google Maps.)

The town allocated public money to try again in 2020, hiring a consultant for $280,000, according to figures provided by Town Engineer Greg Sommer. The consultant recommended a six-month trial project that began in September of 2021.

Measured by trial period data, there was a significant reduction in crashes (down to 16 in a six-month period from a high of 51) and a slight reduction in speed. According to speed data in the consultant’s report, the 85th percentile speeds along North Main Street between Fern Street and Asylum Avenue were 46 mph northbound and 48 mph southbound prior to the road diet trial implementation. During the road diet trial, the 85th percentile speeds at this location were reduced to 39 mph northbound and 44 mph southbound, for a net reduction of 4–7 mph.

A very notable change in the crash data was in the category of side-swipe crashes (from lane changes) which were reduced to four from a peak of 27 in 2020.

A final recommendation from the consultant is to allocate an additional $330,000 to pay for some widening of the right of way at one end of North Main to allow for five-foot-wide unprotected bike lanes for the length of the project area, a new signalized non-motorized crossing and some signal timing modifications. Another $60,000 provided the road striping changes, signage, and traffic signal modifications, but not a new bridge that needed to be rebuilt, anyway. Total cost: $745,000.

Road diets are meant to be cost effective, but they don’t always work out that way because they face massive public headwinds. A big, controversial road diet I advocated for in Anchorage, Alaska, involved a lot of new construction and took 20 years and at least $10 million of bonded debt for less than a mile of improvements.

So is it worth doing?

Road diets save lives and prevent injuries and property damage by making it safer for everyone using the roadway, especially people who are driving cars, the largest group of users for any arterial roadway. It’s become more and more of a common practice on crash-prone roads below a certain volume threshold (less than 20,000 per day) to reduce travel lanes and add a center left turn lane, the basic mechanism of a road diet.

These projects inevitably cause controversy when they are proposed because it doesn’t make sense to non-engineers that removing half of the travel lanes from a four-lane roadway like North Main Street in West Hartford can make the road safer and more efficient, with only a minimum of increased travel time.

It’s counterintuitive, but at certain flow rates the lack of interference from turning traffic, especially left turn movements, makes the roadway more predictable and more smooth flowing. Sideswipes and rear-end collisions can be reduced by almost half. An Iowa Department of Transportation public education project explains in further detail how these changes in traffic movements reduce friction and turbulence—much like the fluid dynamics of water flowing in a pipe—to make traffic flow more efficiently.

Besides improving traffic flow, road diet benefits include reducing travel speeds by narrowing travel lanes with buffers and center turn lanes designed to accommodate emergency vehicles. Space freed up by lane reductions makes room for walkers and bicyclists. Less traffic volume and lower speeds support more pleasant and productive places, places more like streets instead of highways or stroads.

The main reason this project and others like it matter to the Strong Towns approach is that U.S. roadways, especially urban arterials and stroads—as Chuck Marohn explains in the Strong Towns book Confessions of a Recovering Engineer—are designed with speed and volume as the first two considerations. Safety and cost are the lowest priorities for most engineers.

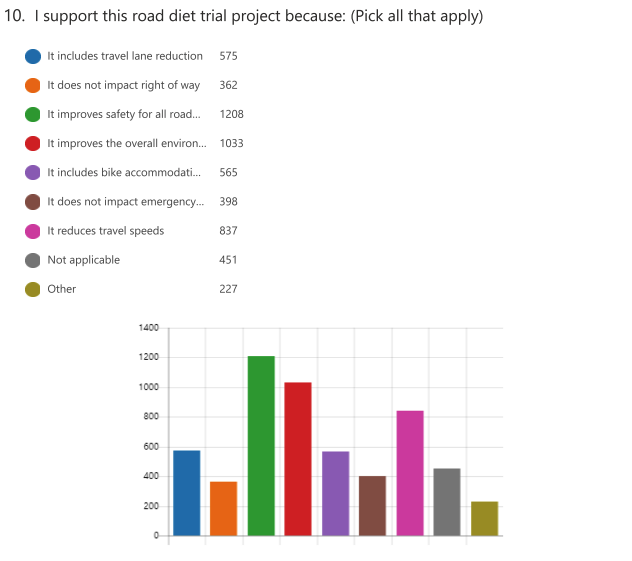

Strong Towns has repeatedly pointed out that most people in our communities would prefer to turn this list of priorities upside down. West Hartford residents answered a survey question during the road diet trial (1,900 respondents) with overwhelming support for the goal of safety over speed and volume:

(Source: “North Main Street Road Diet Study.”)

(Source: “North Main Street Road Diet Study.”)

This alone is a major change in perception for our town: While traffic engineers focus on speed and volume, people who use streets would prefer safety and cost-effective design. Road diets get us there and illustrate this Strong Towns approach to creating safe and productive streets with more economic value.

As in this example, road diets are not always as cheap as the cost of paint. I think this project will produce further dividends if it can be the start of a community transformation to focus more on safety and productivity for our streets, rather than a dangerous and unproductive focus on automobile throughput.

As West Hartford considers other road diet projects, North Main will be a successful example to point out, but why couldn’t we have just done it with cones and spray paint? For these minor physical changes, it really shouldn’t have taken seven years and $745,000. That’s too much for a change-the-striping, basic-road-diet approach. But, like West Hartford Town Engineer Greg Sommer, I think the North Main project has paved the way for the next road diet projects.

“(It) has proven to be very beneficial and we most likely will not need to perform similar studies and trials for future road diet projects, such as the upcoming New Park Avenue Complete Streets project,” he told me in an email.

Ethan Frankel of the non-profit advocacy group Bike West Hartford worked on the North Main Road Diet from the start in 2015. He still remembers a very difficult first presentation. “We were all taken aback by the folks who stood up at that meeting, speaking angrily against it,” he told me. “I feel like (advocates and town staff) were all shocked by the pushback.”

One resident said bicycles were meant for recreation, not transportation, Frankel remembers. “We all knew we were up against a lot of negativity and it seems like we all had PTSD from [one particular] comment and the feeling in the room.” Frankel asked the commenter where her anger and fear came from and he was surprised to learn she had never ridden a bike before and mostly stayed home.

West Hartford needed to change hearts and minds to navigate the headwinds of a very auto-centric culture to get the North Main Street Road Diet in place. I’m glad Mayor Cantor, town staff, and all the advocates stuck with it. And I hope that the next one is a little easier.

North Main Street at Bishop’s Corner (retail center) not included in the road diet. (Source: Author.)

Jay Stange is an experienced community development consultant, journalist, grassroots organizer, musician, teacher, and off-grid project manager. Raised in Alaska, his passions include transforming transportation systems and making it easier to live closer to where we work, play, and do our daily rounds. Find him shopping for groceries on his cargo bike, gardening, and coaching soccer in West Hartford, Connecticut, where he lives with his family. You can connect with him on Twitter at @corvidity.