The Earliest Roots of the Suburban Experiment

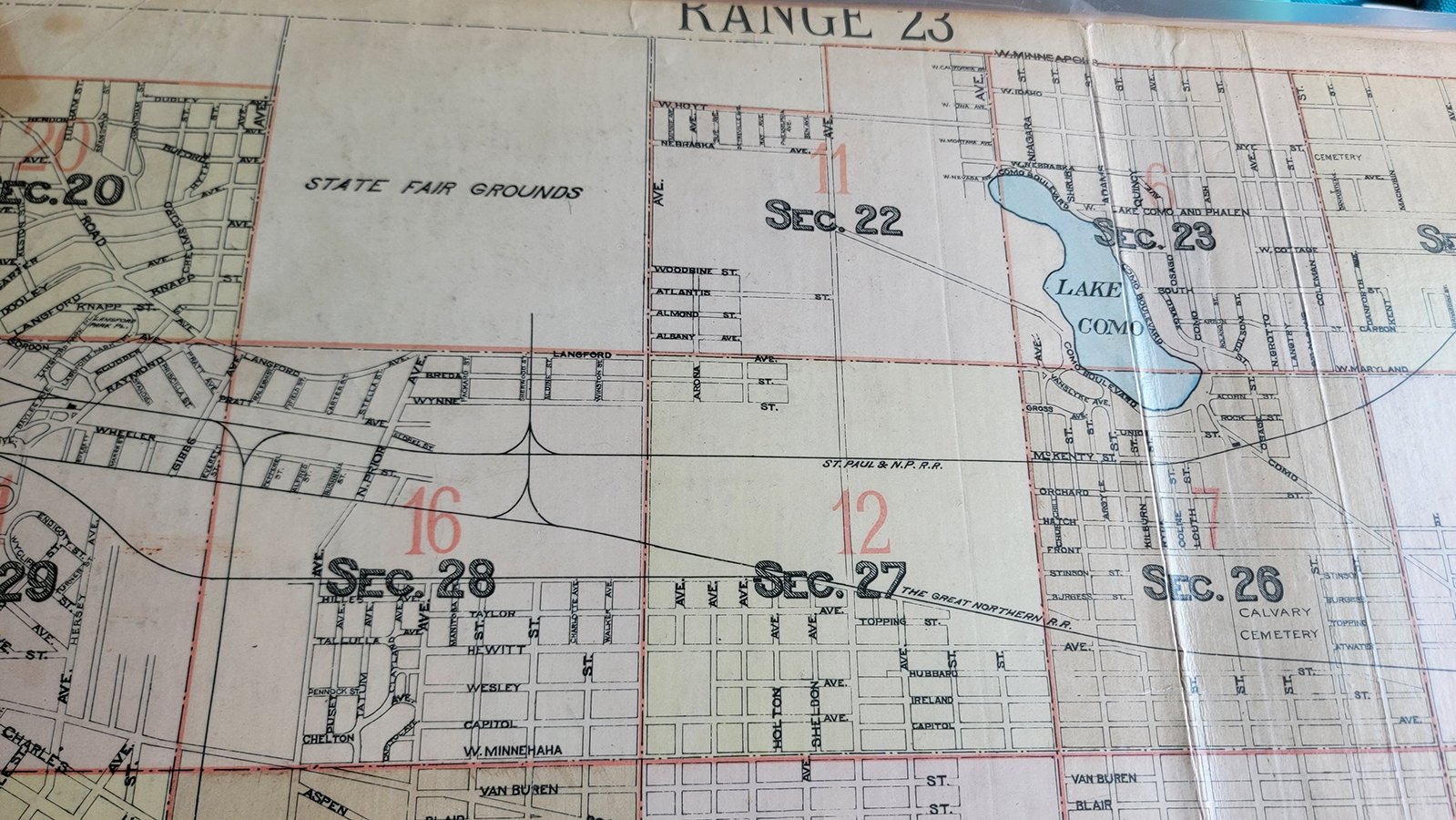

My wife and I enjoy a good antique store, but we don’t have the same priorities. When we popped into one in St. Paul, Minnesota, on a whim a few years ago, she walked out with a lamp, and I walked out with a map. (This will surprise no one who knows me well: I had a map collection when I was five years old.)

What drew my attention about this particular poster-board-sized map of St. Paul, from an 1897 atlas, was that it captures my childhood neighborhood in the process of being developed. You can clearly see little broken extensions of the street grid, a few blocks here and a few blocks there, at the edge of the old city, surrounded by what I presume was agricultural or wild land. A number of the street names differ from their modern ones. The map is a snapshot in time of the development process of the city, one that occurred not by the orderly implementation of a single master plan, but by the incremental replication and extension of existing patterns.

And yet, a deeper look into what was going on at the time, as the burgeoning city carved its way into the hills and fields in the last decades of the 19th century, complicates the notion that what was happening was unplanned or organic.

At Strong Towns, we’ve often drawn a sharp distinction between the “traditional” development pattern of cities around the world and the post-World War II “Suburban Experiment.” The traditional pattern is highly incremental and emergent: development is mostly small-scale and undertaken by many participants over time, and the resulting places are fine-grained and oriented toward people who walk. The suburban model, by contrast, consists of places built all at once to a finished state, using large amounts of up-front financial capital, and designed for mass, if not universal, motor vehicle use.

We often get accused of being ahistorical for insisting upon this distinction. That criticism has merit. Let’s be clear: I believe the “traditional” vs. “suburban” distinction is useful and meaningful. But we can’t use it to draw a firm dividing line between an imagined, pure, or organic past and a corrupted present. There was no single Rubicon, in 1945 or any other year. We have to try to understand the cities of the past as real, messy places, as their inhabitants might have understood them, if we want to learn the right lessons from them.

My ongoing fascination with how things actually developed in the past led me recently to poring over a series of “context studies” commissioned by St. Paul, describing the city’s 19th-century development in great detail. The studies were produced in order to inform modern-day historic preservation efforts. These reports are a window into the earliest roots of what we might later call the Suburban Experiment.

The First Suburbs

It is clear that a huge transformation took place in St. Paul’s development, roughly between the city’s first 30 years and its next 30. St. Paul began in the late 1840s as an informal settlement at, essentially, the furthest upstream landing on the Mississippi River that was reachable by boat. (St. Paul’s twin city of Minneapolis grew up a few miles further upstream around St. Anthony Falls, both a natural barrier to navigation and a convenient source of power for the flour mills that became that city’s economic engine.)

From the 1850s through the 1870s, almost 100% of St. Paul’s development was centered on the river landing and the relatively flat land within a walkable radius of it. There was no other choice: walking was the only game in town. Settlers built upon an early street grid, but there was no master plan and no orderly separation of activities: homes, shops, civic buildings, and industry were interspersed. The working classes lived a stone’s throw from the rich. The high bluffs overlooking the river were mostly unpopulated, due to the difficulty of ascending them as part of one’s daily travel.

1874 panorama of St. Paul.

By the 1880s, though, St. Paul’s population was exploding, and land speculators began carving up the city’s hinterlands at a rapid pace. They were aided in this by the new technology of electric streetcars (and often lobbied for the extension of those very streetcar lines). What unfolded was a pattern of developer-led suburbanization that is surprisingly modern in its basic outlines.

The streetcar suburbs of the 1880s through 1920s, though we no longer call them “suburbs,” comprise most of what is today within St. Paul’s boundaries, including the neighborhood where I grew up and that I saw pictured on my vintage map. They accommodated extremely rapid growth. St. Paul’s population quadrupled between 1880 and 1900, from about 40,000 to about 160,000. (Its present day population is about double that again: 311,527 in the 2020 census.)

There were lots of places in the U.S. where the poor were building shacks on the edge of town in the 1880s, but that wasn’t how St. Paul, or other large Midwestern cities, grew. Large-scale speculative developers were an integral part of our history, and there’s no point pretending otherwise. In fact, the names of the real-estate barons of the time are immortalized in many of St. Paul’s street names today.

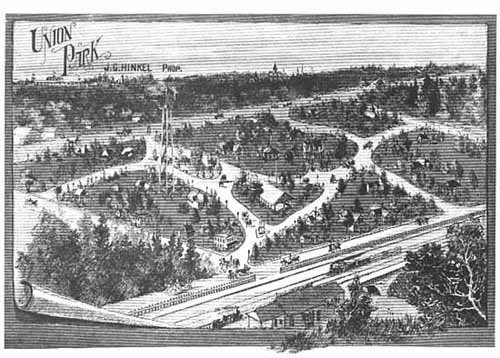

As you follow a rough line between downtown St. Paul and Minneapolis, you pass a series of neighborhoods—even today—with “park” in their name: Union Park, Merriam Park, Desnoyer Park, St. Anthony Park. The description of how the “Parks” came to be is not at all unlike the origin of modern suburban subdivisions. They were master-planned and mass-marketed communities for the upper middle class. Their developers sold them with an appeal to values that are basically suburban: healthy air, peace and quiet, a pastoral refuge from the chaos of the city.

Union Park, 1886.

The Northwest Magazine in 1885 sang the praises of these new residential enclaves:

All large and growing cities throw out suburban villages that serve as quiet retreats for businessmen who get enough of the noisy town during their working hours in offices and stores, and like to make their homes in the midst of the restful influences of nature. … The inter-urban district is high, well drained, and entirely free from all influences injurious to health.

A master developer would subdivide a neighborhood into individual streets and lots, and then separate builders handled homebuilding on those lots. The developer typically provided for a commercial center, and designated space for civic features such as schools, parks, and churches. Neighborhoods were largely built out over the course of a couple decades. Here’s the thing: this is still a basically accurate description of suburban development today, whether you’re in The Villages, Florida; McKinney, Texas; or Maple Grove, Minnesota.

Years before zoning became a standard feature of every city’s bylaws, these incipient suburbs used deed restrictions to impose a standardization and predictability that was lacking in the city’s earlier (1850–1880) phase of growth. We see here the first glimmers of a different way of understanding the city.

"Are you concerned about the kind of improvements that may be placed on the lot adjoining your home?" asked a 1909 advertisement for lots in the Roblyn Park subdivision, in which “no duplex, double house, store, flat or tenement house was allowed.” In other streetcar suburbs, restrictive covenants established a minimum sale price for any house that could be built.

The streetcar suburbs are the prototype not only of the economic entity that is a commuter suburb, but of the ideology that would come to characterize American suburbia. This ideology would later be articulated by real-estate titans such as J.C. Nichols of Kansas City, whose 1948 speech, “Planning For Permanence,” to the National Association of Realtors is as close to a manifesto for the Suburban Experiment as I’ve ever seen. Nichols sought to do away with what he perceived as the senseless waste wrought by the incremental redevelopment and evolution of cities. Instead, he proposed that places be carefully and scientifically planned, every detail accounted for from the placement of parks and shopping centers to the size of homes—and then, said Nichols, they should remain unchanging.

“We are the men to lead the attack” on incremental city-building, Nichols told the assembled real-estate professionals. This attitude did not begin with him. Its seeds lie far earlier, carried on the winds of the broader modernist transformation of society, and the ascendant 20th-century cultural belief that there was nothing organic that could not be perfected with scientific management.

Scale Matters

Nonetheless, there are huge, meaningful differences between the streetcar suburbs of the end of the 19th century and the automotive suburbs of the end of the 20th. It is in these differences that we find the key to why so many streetcar suburbs—despite their inorganic elements and the role of top-down planning in their creation—hold up so well today as beloved and highly functional places.

Foremost among these factors is physical scale: in the 1880s and onward, we were still building places at a human scale for people who walked. A streetcar-oriented community—the predecessor of today’s TOD—is centered upon a walkable radius around the transit station. In cities like St. Paul, although the streetcars are gone, the station locations can easily be identified today by clusters of commercial buildings that serve as neighborhood mini-downtowns. These provide a local sense of place, and enable some degree of freedom from car dependency.

Quite simply, walkable places work, and those which originated as large bets versus small bets still have big commonalities.

There is also a difference in economic scale between the suburbanization of the 1880s and that of today. Back then, there were many more and smaller firms involved in the creation of a new neighborhood. The superficial similarity in the process—a master developer and subcontractor builders—may disguise that this was a much more local economy with shorter feedback loops than we see today. The builders were local firms, not national goliaths like today’s Pulte or Lennar. The houses followed common templates, but they weren’t identical down to the paint color and the trim. Many smaller subdivisions, as small as a block or two, filled in the interstitial spaces between more ambitious master-planned villages: in total over 1,800 separate additions had been platted in St. Paul by 1912.

The size of these subdivisions was smaller, and they were much more interconnected with the rest of the city, building upon the existing street grid instead of turning inward and away. (Walkability required this kind of connectivity: the comical extra distance that we routinely require drivers to travel today would have been a non-starter.)

This is a source of greater resilience in a number of ways. Neighborhoods contain more diversity of housing sizes, styles, and price points, and don’t suffer from the problem typical to blocks of identical homes, in which they all physically deteriorate at the same time. Connectedness to the street grid reinforces the value of location: while the marketing brochure for early suburbia might have emphasized pastoral serenity, these places worked because they were accessible to more established neighborhoods and the amenities and businesses to be found there.

In a modern gated or otherwise walled-off community, on the other hand, you’re selling exclusivity and isolation, not connectedness. And this means that each new home nearby only degrades the value of that sales pitch, instead of enhancing it. It’s a perfect recipe for NIMBYism and stasis.

Truly small-scale developers and individuals could participate in the growth of the streetcar city, in a way that they can’t today. The bar of entry was lower. You could buy a single lot and custom-build your house, and you could probably even put up a small apartment building, have an ADU in the back or a retail storefront downstairs. Zoning had yet to shut down those options in these St. Paul neighborhoods, though we were already seeing the beginnings of the desire for homogeneity and control as a marketing approach.

The Manicured Suburbs Versus the Messy Core: Cycles of Decline and Rebirth

We often commit the error of compressing pre-World War II urban history into “old” in our minds—at least I do. But St. Paul had been a city for 100 years at the end of World War II! By then, it had undergone multiple cycles of massive change, long before the freeways came through and middle-class and white flight to the suburbs ensued.

The most fascinating of the historical context studies I stumbled upon concerns not streetcar suburbs, but rather the neighborhoods built before the streetcar era, which were almost entirely within walking distance of downtown (though there were horsecars from the 1870s), and which were truly built without master planning. The context study calls these the “neighborhoods at the edge of the walking city.”

In these “edge” neighborhoods, you would have seen a more unplanned mixture of commercial and residential uses. The evidence of this survives today in things like an old bakery building on an alley in the middle of a residential block.

The mixing of social classes was also the norm on the edges of the walking city, as the working classes sought cheap and available land to make their homes. The very idea of working-class neighborhoods that developed as such is almost nonexistent today: the cost of development pushes rents in essentially all new buildings out of reach of lower-income residents. America has almost completely ceased to build or permit starter homes. The closest thing today to what, say, Frogtown was in the 1870s would be a new mobile-home park at the fringes of a metropolitan area. This of course happens, but these places aren’t viewed as desirable by planners. Far more often, today, that land at the outer edges of development, accessible to the metro by freeway, gets carved up into generous suburban estates for the upper classes.

The neighborhoods of the “walking city” in the 19th century were subject to incremental change by many hands, and as a result were quite unstable. Their fortunes rose and fell dramatically. Sometimes this was due to changing demographic or market forces which pushed a place into a tipping point of rapid transformation. Sometimes it was due to heavy-handed government actions. The controversies surrounding gentrification and displacement we have today are not without precedent in the more distant urban past; this isn’t a new phenomenon.

St. Paul’s largely forgotten history includes the fascinating case of Lafayette Park, an elegant neighborhood where many 19th-century elites had their mansions. Today, the site of the grand fountain in the neighborhood’s eponymous park is marked only by a manhole cover in a parking lot near some warehouses and the drab headquarters of the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources.

Lafayette Park’s decline wasn’t imposed from the top down, the way urban renewal schemes a couple generations later would condemn whole blocks to the wrecking ball. The rich simply moved away as the railroads came through and brought industry to their doorstep, and as streetcar technology made more attractive sites up on the bluff newly available. The neighborhood first became a lower-class residential area, then was abandoned entirely to industry. It transformed rapidly, but not in a top-down way. This is not too unlike the flight of urban wealth to the suburbs in the mid-20th century.

Central Park, on the other hand, is another lost St. Paul “park.” This one fell victim to top-down plans: the creation of the state capitol complex. Its location is now a parking garage.

Central Park, 1895.

Learning From the Past Without Romanticizing It

The Strong Towns approach is a vision for how cities can better achieve antifragility and iteratively become more prosperous and suitable places. It’s no accident that America’s oldest neighborhoods, and the ones with the most intact pre-car fabric, tend to be the most successful today. If there’s a core lesson there, it’s, “Hey, there’s evidence all around us of what works. Let’s learn from it.”

I love St. Paul for that older fabric, especially the eclecticism of the city’s oldest neighborhoods. The still-intact places that were functioning communities by the close of the 19th century offer both remarkable beauty and functionality today. Our forebears did a lot right.

But we can learn from it without falling into the ahistorical trap of romanticizing the past. Cities were nastier places a century ago than they are now. They were less healthy, more polluted. They were in many ways more unequal. Some of our most beloved places today weren’t built by noble, resourceful bootstrappers, but by ruthless profiteers. And the people of the pre-car city weren’t exempt from the concerns about change and displacement that trouble city-dwellers today.

If we want to understand what real, practical space there is today for a revival of Strong Towns principles—incremental development with a lower bar to entry, allowing places to be co-creations of many hands, resulting in a fine grain and human scale—then we should want to have an accurate understanding of how the places we hold up as models came to be.

Daniel Herriges has been a regular contributor to Strong Towns since 2015 and is a founding member of the Strong Towns movement. He is the co-author of Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis, with Charles Marohn. Daniel now works as the Policy Director at the Parking Reform Network, an organization which seeks to accelerate the reform of harmful parking policies by educating the public about these policies and serving as a connecting hub for advocates and policy makers. Daniel’s work reflects a lifelong fascination with cities and how they work. When he’s not perusing maps (for work or pleasure), he can be found exploring out-of-the-way neighborhoods on foot or bicycle. Daniel has lived in Northern California and Southwest Florida, and he now resides back in his hometown of St. Paul, Minnesota, along with his wife and two children. Daniel has a Masters in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Minnesota.