In the Name of Urbanism

This article is published as part of Strong Towns’ ongoing partnership with the data analytics firm, Urban3. Visit this page to learn more.

Another permit review, another multi-family development. Across the U.S., cities are getting more and more 5-over-1 developments, or some form of “boxy, mid-rise building.” Amid a country-wide housing affordability crisis, projects are pushed forward under the guise of necessity.

A site in Asheville, North Carolina, is subject to a new development proposal to build multi-family housing. The proposed project is across the street from The District, another multi-family development built in 2017, and a couple of blocks from River Mill Lofts built in 2019. YIMBYs rejoice! Housing production is chugging along. But I wonder, is this good design?

The project would be replacing a beloved antique store, “ScreenDoor.” I’m not here to lament the loss of that particular institution or to argue against change generally. I do think this scenario poses a larger question, however: Are we building things that meet—or exceed—the value of what they replace?

The District generates $3,942,289 per acre and River Mill Lofts generates $3,541,723 per acre. Site of new development highlighted in orange.

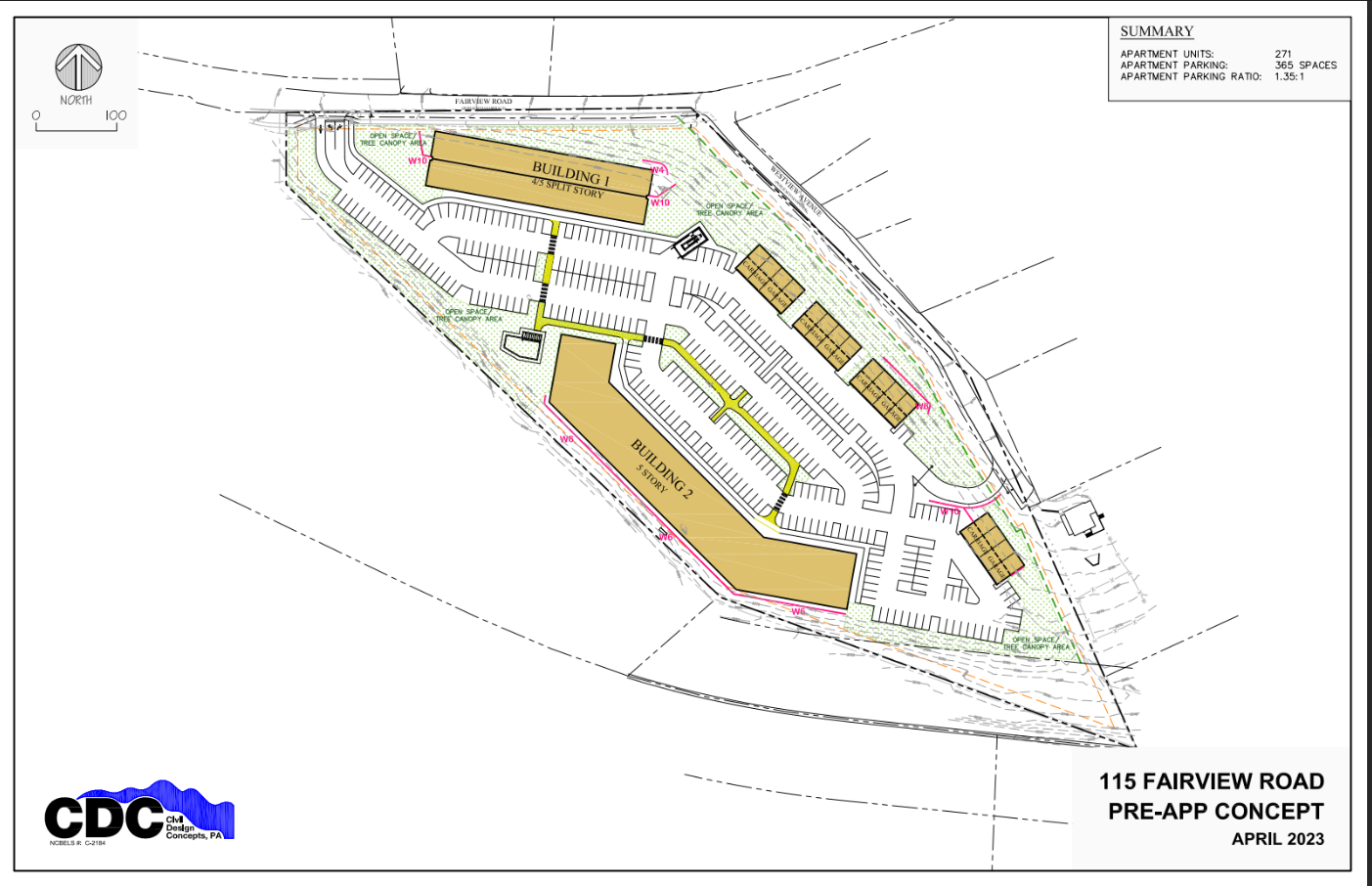

These apartments are located in South Asheville, an area that, outside nearby Biltmore Village, lacks a connected, walkable street network. The new development would have a mostly stepped-back relationship with the street. The majority of the site would remain surface parking, with building footprints coming in the form of three- to five-story apartment buildings. The buildings themselves are dense, but the site design feels suburban.

New development proposal.

Think of The District across the street. It actually does have ground floor activation, but half of the buildings are set back behind parking. Think of what it’s like being a resident in one of those buildings, where the space between you and the road is defined by surface-lot parking. To use a design term, the affordance to drive is high, and low to walk.

A Lost Alternative

Given the issues with the street network in this area, are we destined for these kinds of developments, or are there other options to pursue? It turns out that Seth Harry and Associates, Inc. and Daryl Rantis Architects had a more comprehensive vision in the early 2000s. Their proposed design would have created a walkable village with a variety of housing types in a type of compact development comparable to what exists and is being proposed.

This proposed development would have encompassed The District’s site, as well as the new development replacing ScreenDoor. Instead of two large developments disconnected by surface parking, these structures would have been part of a neighborhood built at a human scale. Instead of a site plan built around car storage, there would be a site plan built around connectivity and walkability. The neighborhood would have streets safe enough for children to play on. These aren’t just whimsical ponderings. They are very real things we lose when we forget the human element integral to good urban design.

A proposal like this doesn’t fit into the regular development process. It's an expansive, visionary plan born out of a community engagement process that would require substantial private and public collaboration to be implemented. Planning this site required addressing steep slopes and irrigation needs to implement contextual architectural design and gentle density, all while weaving a new neighborhood into an existing community. Planning this way takes time, but the quality and attention to detail are the return on investment.

Auto-Oriented Density (AOD)

Recently, I’ve noticed that more arterial corridors are deemed suitable to handle highly compact development. In Buncombe County’s recent draft comprehensive plan, mixed-use districts are spread linearly along major corridors. These corridors are currently designed to move lots of vehicles at high speeds. However, the future land use map assumes that they can also accommodate access for compact, mixed-use development. They will be expected to accommodate both throughput and access. Sound familiar?

Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) is the idea that compact development can and should be concentrated at important intersections along major transit corridors. However, some urban planners have taken this concept and determined they should allocate all their proposed compact development along the local stroad. It’s not TOD when there’s no transit and the only way to walk from place to place is along a highway.

In his book Rural by Design, Randall Arendt covers the concept of the “townless highway and the highwayless town.” This concept puts forth that development should not occur alongside a road (not to be confused with a street), creating a “motor slum,” but off the road in nodes or “stations.” When Benton Mackaye and Lewis Mumford originally introduced this concept in 1931, they called it the “divorce of residence and transport.”

Projects like The District offer semblances of urbanism, in density and form, while fulfilling the promises of privacy and driveability offered by suburbanism. Sure, you’re living in an apartment building, but you’re promised a parking spot and exclusive amenities. They take the ethos of suburban development and make it vertical. They offer the illusions of Transit-Oriented Development but deliver Auto-Oriented Development.

When this kind of “vertical sprawl” is built in urban areas, it wastes valuable space, degrades urban form, and ruins the opportunity to maximize compact development and walkability. When it’s built in suburban areas, it adds development where walking is already dangerous and car traffic is horrendous. Auto-Oriented Density is similar to a stroad: they seek to accomplish two diverging goals at once—compact development and drive-ability—with reduced returns on both goals.

Not to mention, putting “affordable” housing in driving-required areas sets people who can’t afford a car up for failure and, potentially, worse health outcomes. Cities should question the impact of piling people alongside roads with high traffic volumes that emit pollution and noise. According to recent studies covered by the New York Times, “Those who lived in areas with high levels of transportation noise were more likely to have highly activated amygdalas, arterial inflammation and — within five years — major cardiac events.”

Other urban forms have been bastardized by sprawl as well, such as the shopping mall. Originally intended to introduce Americans to walkable urbanism, the inventor today regrets popularizing the concept. While very walkable inside, malls care little for their surroundings and are nearly always located in drive-to suburbia.

Some malls, like Dania Pointe below, are trying to lean more into their appropriation of urbanism by making their interiors feel more like streets. If I didn’t tell you the following image was from a mall, would you know?

Admittedly this mall’s design is quite impressive—yet it’s still just a mall in open-air form. Hallways are converted to streets that feel like boulevards, providing drive-to-walk urbanism for suburbanites. From above, it’s easy to see the trick being played here. There is a 350-foot walkable strip, but no way to walk to Dania Pointe.

Exercise and good civic design have become premium goods, only available in limited doses to a privileged, paying few.

Urban “Boulevards”

Cities should also be careful accepting plans to replace highways with urban “boulevards.” Much like housing, there is general consensus that removing highways from downtowns is largely a good thing. If the end product is more stroad than street, local leaders should ask if the effort and expense justify the result.

For instance, MDOT’s plan for I-375 in Detroit narrows the right-of-way that the highway takes up and creates developable lots that will attempt to repair the lost street grid. This effort will likely enhance the vibrancy of this area and improve tax revenue. But the renderings are less like a boulevard and more like an at-grade highway.

Asheville Infill

Asheville is no stranger to infill development, in either its downtown or its historic neighborhoods. Even its famed and historic Montford neighborhood (median sale price of $600,000) has apartment buildings. The building below could not be built today since it violates the density maximum and minimum setback requirements of Asheville's RM8 zoning, a purportedly “Medium Density District.” Only two dwelling units would be legally allowed here now, as opposed to the current six.

$3,761,000 per acre.

The Garage Apartments downtown fit over 30 new housing units on a strip of land less than 40 feet deep.

Garage Apartments by Public Interest Projects, Alberice Architecture + Design, Rowhouse Architects, and Garanco. $31,430,714 per acre.

This development occurred in Asheville’s Central Business District zoning area, which ironically allows the type of development we would expect to see before the invention of modern zoning. It relaxes parking requirements and setbacks so new buildings can fit into the existing urban fabric.

If Asheville is to grow upwards, downtown is precisely where they should be doing this. Downtown housing units just surpassed 50% of all housing and hotel units. Asheville’s downtown vibrancy is due in no small part to visitors, and tourism is, of course, a major economic driver here. It is possible to balance tourism with residential priorities, and we should still build more housing for locals. There is no shortage of underutilized surface parking in West Downtown, a prime location for car-lite development.

Conclusion

In today’s difficult housing market, more units of housing anywhere are generally good. What isn’t so good is piling more people into neighborhoods where driving is essentially required. This choice creates congestion while diminishing the very things people crave about cities: positive public health outcomes, vibrant social life, and resilient, interesting communities.

Planners and politicians, therefore, need to be more intentional about allowing compact development to occur where the market wants it and where its financial and environmental benefits will be most readily realized. There is too much opportunity downtown to allow auto-oriented development to get worse under the guise of “urbanism.”

Billy Cooney is an analyst at Urban3 where he crunches data on tax policy and land use. In 2022, he earned a Master’s in City Planning from Georgia Tech, focusing his studies on urban design and GIS. Prior to graduate school, Billy worked in the public sector where he helped write plans and policies for multi-modal transportation and affordable housing. Before that, he studied urban history and the sociology of public space at New College of Florida.

Are there any instances where sprawl is actually good? Hear Strong Towns President Chuck Marohn discuss this with Joe Minicozzi, principal of Urban3.