Lessons from the Streets of Tokyo

I had the good fortune to visit Tokyo, Japan in early August. I couldn’t help but compare and contrast that city to the cities and towns back in the United States. There are four elements of Tokyo I want to highlight in particular: its urban biodiversity, how they control the speed of cars, their approach to off-street parking, and the way they utilize every available last bit of land.

Urban Biodiversity

Cities are living organisms, not machines, and just as we are drawn to biodiversity in natural settings, we are similarly drawn to urban biodiversity. I loved the urban biodiversity of Tokyo’s different neighborhoods and streets:

Segregating Street Space by Speed

The Toronto proposal from Sidewalk Labs threw around the idea of segregating street space by speed, rather than the more common approach of by vehicle class. We tend to segregate our streets by giving dedicated space to pedestrians and dedicated space to motor vehicles. Often on narrow streets, the result is very uncomfortable. We build streets with skinny little sidewalks (sometimes with tree trunks in the way) because we believe the asphalt in the middle is for cars and the way to accommodate people is to build sidewalks.

Sidewalk with a tree trunk in Hoboken, New Jersey.

Tiny little sidewalk in Boston.

I have criticized this approach before in my article on Complete Streets, because what results from this framework — giving every mode of transportation its own dedicated space (wide sidewalks, bike lanes, parking, car lanes, bus lanes, benches, etc.) — is what I call a "fat street": a very wide street that tries to do too much and is expensive both to build and maintain.

A fat street that tries to fit in as much as possible. (Source)

The Japanese take a different approach. Narrow streets are uncomfortable to drive on so cars do not drive fast. When cars drive slower (less than 20 miles per hour), people and vehicles can safely mix.

It makes sense to separate cars and people on wider streets where cars can go faster and would be dangerous to pedestrians.

The narrow streets were safe and pleasant, both because they felt very human-scale and because of how few cars you actually encountered as a pedestrian. These streets did not have to ban cars. Because they were uncomfortable and inefficient to drive through, and because there is often nowhere to park unless you lived on the street, drivers avoid these streets unless this is where their journeys began or ended.

I was also impressed with how quiet the city was, especially for a dense urban area in one of the world's largest cities:

This following scene is particularly interesting. This is a sidewalk near a major road. Yet the cyclist is cycling alongside the people on the sidewalk, rather than among the fast and dangerous cars. I like this, because it makes more sense for the cyclist to be grouped with the human-scale speed of pedestrians, rather than the high-speed cars.

I am sorry that the cyclist is so small (in the distance, to the left of the ramp. His bicycle has a light.) I could not capture the photo fast enough when he cycled past me.

This would not work in New York City because of how narrow our sidewalks are in relation to how many people use them:

Try to cycle on the sidewalk here and you would bump into everyone. For how wide the avenues of Manhattan are, very little space is allocated to people; they are even overflowing into the bike lane!

Off-street Parking

When you have sidewalks, having a lot of off-street parking is generally considered a burden because it results in a lot of curb cuts — interruptions to the pedestrian-only space that often feel like an intersection crossing.

I was surprised at how many residences had off-street parking in Tokyo. When people are free to occupy the entire street, there is no curb to cut. And when the granularity of the street is maintained there is a front door every few dozen feet that is flush against the street. As a result, off-street parking was not as invasive as it would have been in an American city. Often I did not even notice it I was walking past a parked car.

Utilizing Every Inch of Land

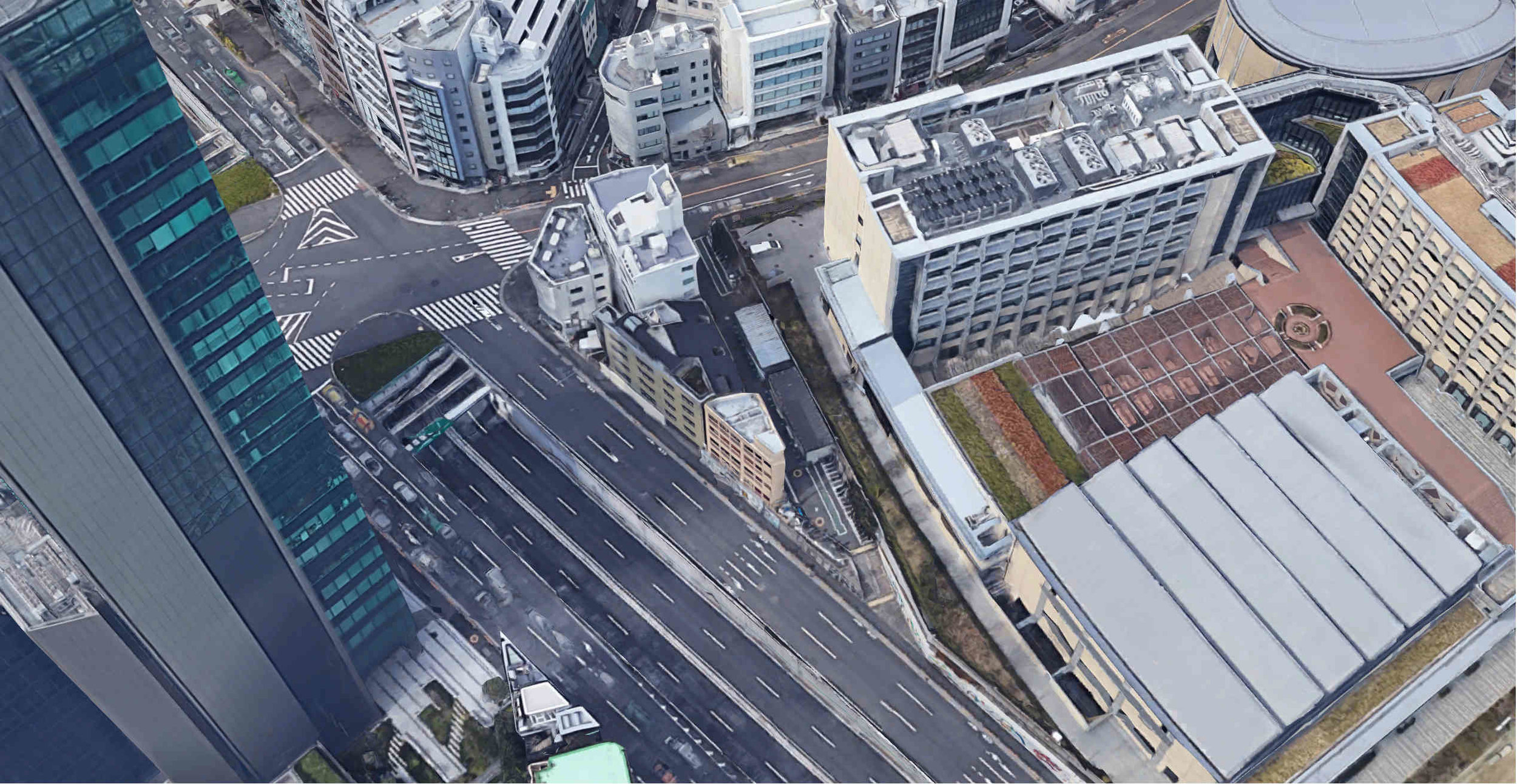

I hate seeing wasted space in cities. This is space that could be put to productive tax-generating use — providing us with more housing, more amenities, more businesses. It was wonderful to see how in a place like Tokyo, where land value is high, the Japanese utilize every nook and cranny. This is the space between two elevated rail lines:

I loved how safe and inviting it felt. It did not feel as if the elevated structure (be it a rail line or a road) divided the neighborhood in half.

And land that could be built on, was built on. These buildings fit nicely in a shallow triangle of land up against a major highway:

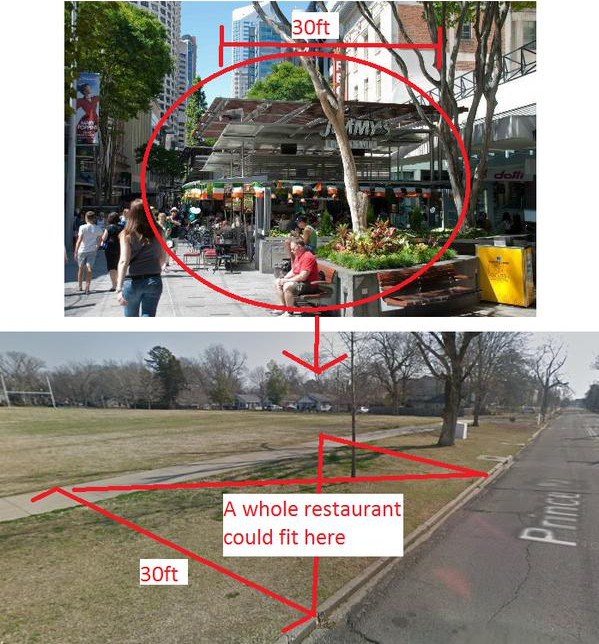

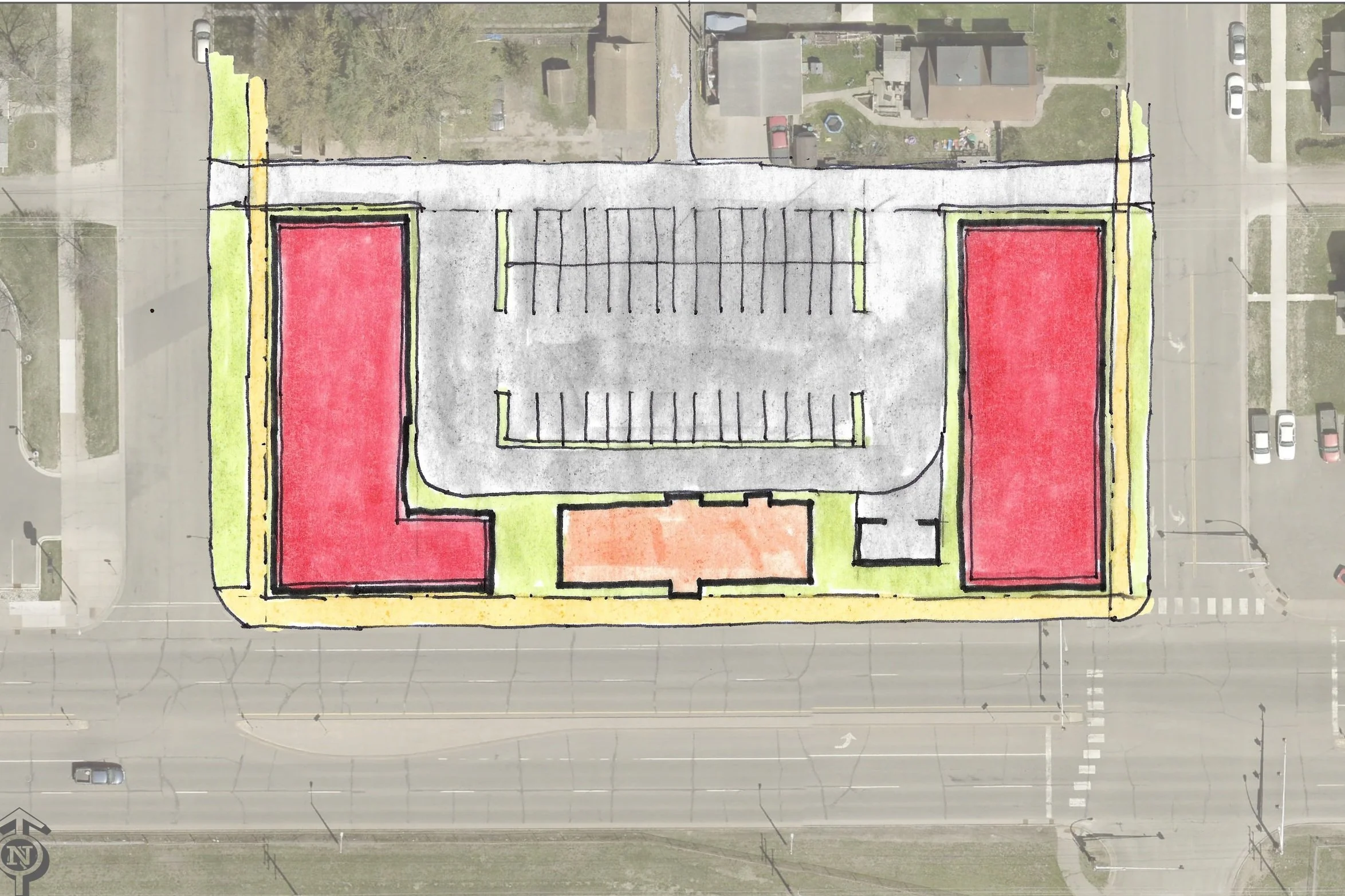

This makes me think of the untapped potential of all of those useless patches of greenspace around highway ramps in urban areas, and the space we waste by large setbacks, minimum lot sizes, and lot coverage limits. I made this image four years ago and it is worth re-sharing here:

I took the bottom photo while walking down the street thinking about how I have seen businesses take up less space than width of the sidewalk and setback.

Conclusion

My trip to Tokyo was fascinating. There is a lot we can learn from the Japanese on how to build great cities. I loved exploring the diversity of the neighborhoods. The Japanese have really taken to heart the lesson that one size does not fit all, and there is an obvious division between streets (which are the platform for building community and wealth) and roads (which are a tool for getting from A to B).

And yet, for as much as I adored the city, living there permanently would be struggle. I would miss the traditional architecture and older buildings from where I live now. Like all good travel, my visit to Tokyo helped me appreciate the home I was coming back to — even as it reminded me of things we could be doing better.

According to the United States Census, prior to the pandemic, half of all businesses in the U.S. were home based and nearly eight million people worked primarily from home…but according to urban planners, this is illegal!?