How Incremental Development Came to Miami

You have read a lot on Strong Towns over the past several years about incremental development, both of infrastructure and buildings. Strong Towns’ evangelization, which began in 2008, is part of a larger movement in favor of fine-grain planning and small-scale development. I would like to talk about how the movement has unfolded both in the United States and abroad, how I came to be involved, and how it is shaping my own work as a developer and advocate in Miami.

The Movement Over Time & Space

This movement is, fittingly, made up of many proponents, not one main champion.

It had a champion, as did many of the best urban planning ideas, in Jane Jacobs. But after Jacobs the topic seems to have disbursed, proverbially wandering in the desert, finding infrequent outlet in disparate places like The New American Townhouse, by Alex Gorlin (2000); Pet Architecture, by Atelier Bow-Wow (2002); the New World Economics blog by Nathan Lewis (2006); The Urban Housing Handbook, by Eric Firley and Caroline Stahl (2009); and “Density Without High-Rises?,” a seminal 2009 article by Ed McMahon.

In 2010, the topic finally registered with my dim intellect. That’s when I started paying attention to what smart people were saying and writing. It seemed that I stumbled on the topic around the same time that, to paraphrase Arlo Guthrie, it became a movement:

Old Urbanist Blog, by Charle Gardner (2010)

Singapore Shophouse, by Julian Davison (2011)

“Reinventing Real Estate” by Jim Heid (2011)

Launch of ULI Small Developer Forums (2012)

House in the City, by Robert Dalziel and Sheila Qureshi (2012)

“Limits of Density” and “For Creative Cities, the Sky Has Its Limit” by Richard Florida (2012)

And in 2014 and after, the movement took hold in more institutions:

Launch of “small balance” loans by Freddie Mac for small apartment buildings (2014)

Launch of Lean Urbanism (2014)

Launch of Incremental Development Alliance (2015)

“Older, Smaller, Better” by the National Trust for Historic Preservation (2016)

Making Massive Small Change, by Kelvin Campbell (2018)

Every year from 2015-2018, I organized a Small Summit. We convened leaders from a variety of sectors—Strong Towns, AARP, Congress for a New Urbanism, the American Institute for Architects, and the Urban Land Institute, to name just few. We met in one conference room for one day. During our short time together, we shared any and all achievements from the previous year related to small and incremental, we made plans for the coming year, and we looked for opportunities to collaborate.

In fact, the movement of the small and incremental went beyond the fields of urban planning and real estate development. In addition to Strong Towns favorites by Nassim Taleb, books like New Kind of Science by Stephen Wolfram and Cathedral & Bazaar by Eric Raymond taught us that the small and simple can create incredible complexity, increase both efficacy and participation, and maximize risk-adjusted financial returns.

The “how” of small and incremental development is founded on an even more important “why.” Charles Montgomery wrote about it in The Happy City. But I want to give the last word to Richard Sennett. He is the author, most recently, of Building and Dwelling: Ethics for the City. But back in 2011, Sennett wrote:

I’d like close these remarks about the quality of life in cities by focusing on the Holy Grail for urban designers like myself, the quest to build truly mixed-use environments in order that the inhabitants develop a more complex, adult understanding of one another. […] The key to this kind of planning is informality: leaving the mixed spaces loose in form, open to a succession of small entrepreneurs and businesses. […] My argument to you is that alertness and attentiveness to the unfamiliar, the strange, and the uncertain is an adult strength, a form of human development which urban designers and planners like ourselves can foster by taking down the internal, isolating walls of the city.

That sounds like an urban neighborhood where I’d like to live!

The Movement in Miami

I did what I could to help support the movement in Miami. In 2012, I wrote a grant to the Knight Foundation to fund for four years a small urban building prototype course at FIU School of Architecture. The course was designed by department chair Jason Chandler, who also made it a mandatory graduate course and has continued the course to this day with other funding.

Hi-Res Miami. Plans available for free here.

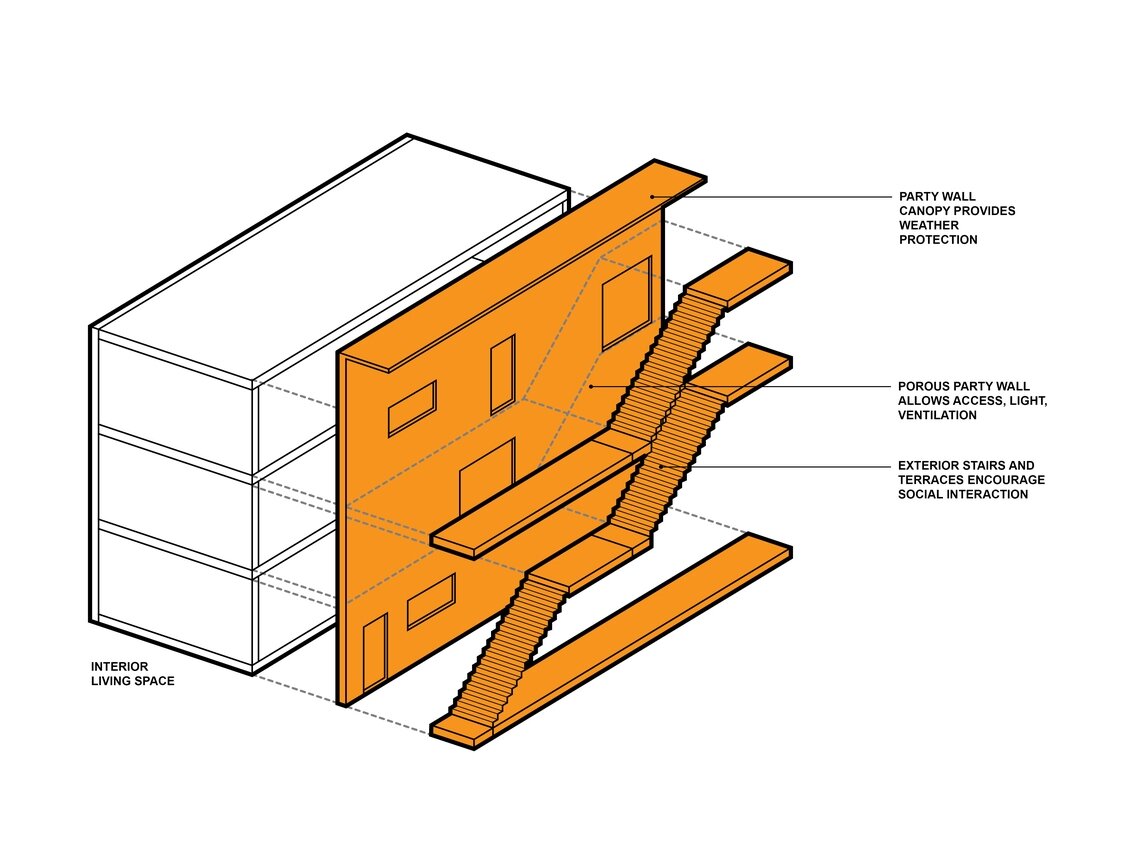

That same year, I wrote another grant to the Knight Foundation to fund architect Brian Phillips of ISA to apply in Miami what he had learned designing his famous “100K House” small urban housing prototype for Philadelphia. We put his “Hi-Res Miami” plans online for free and provoked some discussion, but we knew that the prototype could not be built because it did not have the on-site parking required by Miami zoning.

Before starting both the studio course and free design projects, I knew that parking requirements would block any attempt to resume fine-grain urban neighborhood development. I say “resume” because the city’s original pattern of development was fine-grain, for example the small apartment buildings of South Beach and Little Havana.

Starting in 2011, I had a series of discussions with the city’s planning department about an exemption from required parking for small buildings. In 2013, I shifted to build support for the idea among a coalition of business and community development organizations. In 2014, with a stack of letters of support, City of Miami Commissioner (now Mayor) Francis Suarez agreed to sponsor the legislation. And in October of 2015, the small building parking exemption became law.

Shortly thereafter, I put under contract a 50 feet-wide lot in Little Havana, closed, and filed at the city a fully engineered set of construction drawings. The drawings were already prepared because two years prior, I had hired Jason Chandler to design a 25 feet-wide, no-parking “brownstone” prototype that I hoped would become legal. I say “brownstone” because it is a townhouse, but not single-family, rather divided into four apartments. (You can download the plans for free here.)

While the city reviewed the plans for building permit, I found investors among family and friends, a construction loan from the only bank based in the neighborhood, and a general contractor who had recently immigrated from Venezuela. I broke ground in mid-2016, completed around a year later, and around the same time bought the lot abutting to the east for another pair of “brownstones” that I recently completed.

I tried to develop these buildings in a way that followed conventions and outsourced technical knowledge as much as possible—most common lot size in Miami, local investors, neighborhood bank, hired architect and engineers, hired general contractor, conventional construction materials and methods—so that other small lot owners would have every reason to think “I can do that too.”

And it has already started to happen. Just on the same block as my projects, two other single lot owners have broken ground on small no-parking apartment buildings. Others around the neighborhood and city are following suit with small no- or reduced-parking buildings.

I hope this is just the beginning of a local movement to change how we build neighborhoods, and who gets to build them.

About the Author

Andrew Frey is a real estate development professional with more than 15 years of experience. He is a developer, zoning lawyer, educator, advocate, and winner of the ULI Southeast Florida Young Leader of the Year. He is the founder and principal of Tecela, a real estate development company in Miami specializing in incremental development projects. (The name Tecela is a play on the Latin word tessella or tessera, which means a small tile for a mosaic and reflects how the firm thinks of each project in its neighborhood.) In addition to Tecela, Andrew is Director of Development at Fortis Design + Build, a firm specializing in creative infill projects in emerging neighborhoods. He is an occasional adjunct professor at the University of Miami School of Architecture, where he won the Faculty Award.

Everyone has an entry point on their journey to taking action for their place. For Bernice Radle, it was witnessing the steady depopulation of Buffalo, NY, and seeing a landscape of unused, unloved buildings headed for the wrecking ball.