Activating Spaces and Developing Places with "The Neighborhood Playbook"

Joe Nickol and Kevin Wright didn’t set out to write a book together, let alone start a full-service urban growth firm. But a coffee meeting about one thing turned into a two-hour conversation about something else.

“My wife and I were moving to Cincinnati,” says Nickol, “and I wanted a good grounding in what was happening in the city. Kevin and I talked about that for all of four or five seconds, and then we talked for two hours about what we were noticing around city growth and development, from his perspective doing boots-on-the-ground economic and neighborhood development, and what I was seeing doing master planning and development planning all around the world.”

Together, Nickol and Wright identified a major gap in the conventional planning process. Think of the conventional approach to planning as a spectrum. On one side, says Nickol, you have the grand visions for the future of a city or a neighborhood. These are the people “camped out in a church basement or rec center, putting dots on a map and talking about what needs to change in 30 years.” On the other end of the planning spectrum you’ve got hope for change—new development, new connections, new parks, safer streets.

“And then,” says Nickol, “there’s the giant gap in-between, where very few plans wander into: What can we do next weekend?”

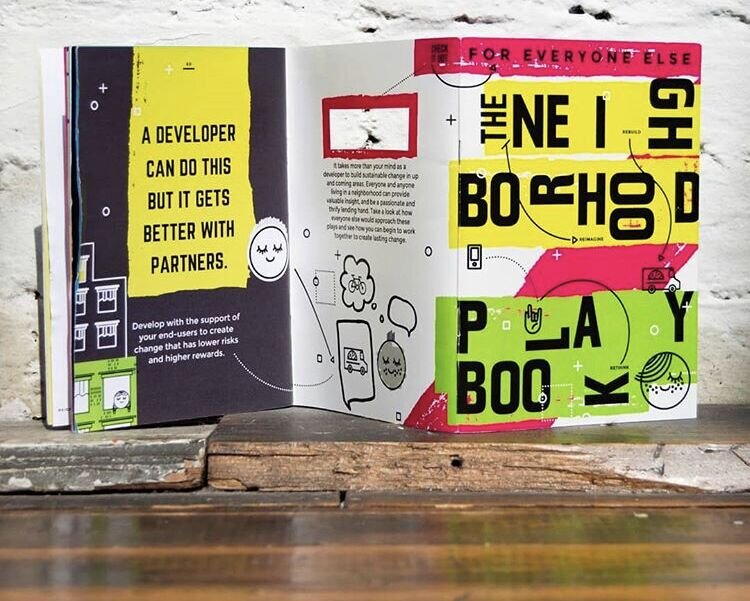

This gap is a significant barrier to creating the kind of resilient, human-centered development that neighborhoods actually want and need. To address it, Nickol and Wright got a grant from People’s Liberty to create The Neighborhood Playbook, an innovative guide to helping both developers and residents create positive change. Later, they founded YARD & Company to build on the momentum generated by The Playbook.

The Neighborhood Playbook is a physical product, not an app or PDF. It is made to be written in, marked up, doodled in, and kept in your back pocket as you walk a neighborhood. Users progress through a series of five steps, or “plays.” And it’s written for both developers and residents (two playbooks in one), but ingeniously designed so that the two groups literally meet in the middle.

This is important, says Wright, because the Playbook attempts to answer the question: “How can development happen with a place instead of to a place?”

I interviewed Joe Nickol and Kevin Wright about The Neighborhood Playbook, its impact in Cincinnati and beyond, the flaws in the mainstream “If you build it they will come” approach, and much more.

STRONG TOWNS

What makes The Neighborhood Playbook approach different?

JOE NICKOL

Typically, development doesn't want to come into a place where the market is untested or nothing seems to be happening. Or, if it does, it's usually incentivized by a massive subsidy to overcome the lack of anything going on. We thought this gap needed filling. A couple steps from how cities have always grown, particularly cities we love, had been value-engineered out of the growth process. The Playbook is principally involved in the first step after planning (which really happens during the planning), which we call Build Demand.

How does the community, or community leadership, or a developer interested in a place create or uncover a story about who would come there, why, and what they would do? The Playbook outlines a process by which this can happen. And, if done correctly, it transitions a property or a place into the next step that's missing, and that's what we call the Smart Small phase, where that tiny foothold—whether it's a corner bar or a coffee shop or a night market or something that creates a more permanent amenity for the neighborhood—starts to make sense because it's been informed by the demand creation phase.

The whole development process becomes not only smarter and more in tune with the marketplace, but it becomes more inclusive of the people who live there. By doing so, it becomes much more rooted in the differences between all of our neighborhoods and, at a bigger scale, between one city and the other.

STRONG TOWNS

Through your approach, developers and residents are in dialogue with one another in a deep way. They’re both considering possible development through the eyes of the other. Do you see this approach as being one that could address concerns around gentrification?

KEVIN WRIGHT

As we were writing The Playbook I was really excited about its potential to help with gentrification. Or at least helping the conversation around it. I think the lack of sophistication around the gentrification conversation acts as a challenge to growth and positive change in neighborhoods—both of which, in my opinion, could be powerful forces in helping to solve problems related to poverty and education and health.

The theory behind The Playbook, as well as YARD & Company, is that if developers and neighbors work together to create the demand for ideas, the demand for growth, then whatever gets developed will be reflective of the community. We’ve seen it on the ground in Cincinnati, and we’re seeing it elsewhere in largely African-American and Latino neighborhoods. The community is showing up and testing ideas and creating ideas; they’re the face of it.

As Joe said, that’s the opposite of how things have traditionally been done, which is that we invite people into a meeting, ask for their input, and then hit the STOP button on engagement. Why are we surprised then when they’re angry about what we built? The Demand Discovery process is a way to keep people engaged post-plan, and really throughout the entire building process.

STRONG TOWNS

That Demand Discovery process flips the script on the “If you build it they will come” approach. Instead you’re talking about getting people to come to the neighborhood first—or actualizing the people who are already there.

KEVIN WRIGHT

In my work before YARD, we had done a lot of “supply stuff.” We purchased buildings, acquired sites. We had a lot of tools at our disposal. And yet, no one was calling me back saying they wanted to put their money into the neighborhood. So, yes, we are flipping the model of “Build it and they will come” to “Come out and they will build it.” We’re getting people to show up, to show that there is a demand, a passion for the place that just needs to be uncovered.

JOE NICKOL

Sometimes we talk about “supply addicts.” In development and infrastructure and city-building at large, sometimes it seems like the building of something is more important than why you are building it. The Silver Bullet Project becomes the pursuit, and not the bigger job to be done through building places. That's a problem.

What we’re finding is that our approach not only makes the planning process better, but most of our projects yield some kind of permanent investment before the planning process even gets done. It also limits the number of white elephant projects that happen. I know that’s a big point of contention for the Strong Towns audience—building giant things that never fulfill the aspirations that were set out for them. We definitely seek to avoid that in our work.

STRONG TOWNS

There are a number of resonances with Strong Towns. Another is the emphasis you place on experimentation and iteration. There is a cycle at work, from pop-up to permanent.

I'd like to ask about the format of The Neighborhood Playbook, because it's striking and, frankly, a lot of fun. Why did you decide to format it as a “playbook?”

JOE NICKOL

A lot of credit goes to the support network at People’s Liberty, who were very committed to working alongside us a grant provider. And we should also mention BLDG, our book designer who helped us make the format as engaging as the written content.

It was important for us to reach two audiences that historically have always been at odds, the development community and what we phrase as “Everyone Else.” We wanted to create a system where those two groups realize in the end that they're playing for the same team. It's an empathy tool where you come together in the middle. You're almost invited, if you are the community member, to flip it over and say, "I wonder what they're telling the developer to do," and you start to understand how a developer might be thinking about this. That drove the format.

The other thing that was really important for us was to have something that was analog, something the right size for you to take out on the walk and use as a live documentation tool. Most people said that we had to make it free and downloadable. However, we felt strongly in the power of holding something in your hands and dog-earing pages.

The Connect Challenge program invites cities to compete for funding to design and install pilot street projects with the community that will inform permanent investment in safer, more active streets. Image credit: YARD

STRONG TOWNS

What has the response been so far to The Playbook?

JOE NICKOL

It’s been amazing. The Playbook turned three in October. Just by the nature of how it was created, it started with a fairly local audience here in Cincinnati—which was kind of the point to the funder, People’s Liberty. However, our network and reach is pretty large, so we started selling them nationally fairly quickly and internationally too.

We were both holding down full-time jobs independent of one another, as well as holding down the fort with growing families. Then we started getting regular requests to come talk about The Playbook, to share the story and the rationale, to share the Demand Discovery process, and what it means for people using The Playbook. By early 2018, we were both now essentially working two full time jobs. We knew we had to shut this down or go all-in. So in April 2018, YARD & Company was launched to take the Demand Discovery process to another level. That's what we've been focused on since.

STRONG TOWNS

Who are some of the people you’ve heard from who are using The Neighborhood Playbook?

JOE NICKOL

We've visited a lot of places where they’re using it, and we have been just blown away. One group early on in The Playbook's formation (they were a bit more local so we could participate more in it), created what was called the Old Kentucky's Maker Market. Long story short, that turned into a permanent market called the Fairfield Market.

Another group, also local, created a project called Unlock the Block which was all about figuring out an area of Covington, Kentucky that was really not functioning as well as it could.

We’re working with a lot of neighborhoods down in Memphis, where they are using The Playbook in a variety of ways. What's cool about it is that we always thought of The Playbook as an amenity creation tool. Yet as we've tinkered with it more and solidified the Demand Discovery model, it's become a methodology that can be used to do everything from reimagining and improving streets, to creating public spaces and activating storefronts. It's been interesting what people have read into it and how they've applied it to the problems they're trying to solve.

With the Neighborhood Playbook a group of five residents developed the Old Kentucky Makers Market (OKMM) that brought together music, local microbreweries, local food and makers with an overtly Kentucky brand. Image credit: YARD

STRONG TOWNS

One last question. I know you’re working not just in Cincinnati but around the region, around the country, and around the world. But I wanted to ask you about Cincinnati in particular because it’s a city I’ve visited five or six times over the last three years. I have friends and acquaintances involved in asset-based community development there, including Megan Trischler from People's Liberty.

The sense I get when I visit Cincinnati and hang out with these folks is that something is afoot in Cincinnati. Is it just my imagination or does there seem to be a higher proportion of people there taking the future of their neighborhoods into their own hands?

JOE NICKOL

That's a good question, and I think Kevin in particular, who's been working in Cincinnati for three times longer than I have, will have some good insight on that. Coincidentally, we just wrapped a gathering of all the neighborhood development leaders of the Cincinnati region to celebrate exactly what you're talking about. There's certainly a lot of creative people here. But I'm going to let Kevin talk about what the secret sauce in Cincinnati is, if there is one.

KEVIN WRIGHT

I don't want to be the guy who thinks the grass is always greener. You know how you always think it's better in other cities? You're kind of doing that in a way. And I'm sure we would come to your place and be like, "Oh my gosh, I wish we were doing that."

I will say that Cincinnati has a strong community development corporation system, compared to other cities. But I don’t even know if that’s an answer to your question because a community development corporation can sometimes be pretty “top-down.” It's amazing how quickly things have changed in Cincinnati. I remember when we started the Walnut Hills Redevelopment Foundation back up, there were no community development corporations utilizing social media. Now they all are. Community development corporations were doing a lot less in the event space and programming space in their neighborhood; now every one of them is doing monthly programming and street festivals and things like that.

With a tiny budget and a little bit of creativity, YARD installed Bird Cages in public spaces around downtown Cincinnati in a matter of hours. Image credit: YARD

And then along came People's Liberty, which was funded by a foundation who said, essentially, "Why is it that the institutions are the ones getting the money? What if we put the money in the hands of people who actually live in neighborhoods and have ideas?" I have to say: People's Liberty just shut their doors. They closed, because it was a five-year experiment, and so they were never going to be permanent. I think People’s Liberty really changed the culture here and changed what's possible, changed the idea of "Somebody needs to do something for me," to "I can go out and do it." I think that, paired with the changes in technology, the national urbanism movement that Strong Towns helps lead, and Tactical Urbanism, these have helped change the thinking here in town.

There's something about community engagement, community activation that can start with a small amount of money and lead to big things. Now I definitely feel like I'm rambling, so I'll stop, but that's my take on it. I think it is often hard to sit in your own city and see the positive things that are happening, and it is really nice to hear you say something like you said about Cincinnati. I think we have a long way to go, but I think we've changed a lot in the last few years.

JOE NICKOL

I’m not from here and I’m still learning to call this place home. And yet there is something comforting about coming back to Cincinnati. We work in all different types of cities, but it's always good to come back. I think that speaks to the magic that this place has, even if we don't acknowledge it all the time.

KEVIN WRIGHT

People who have never been to Cincinnati think of it a certain way. Then they come and realize it isn’t what they imagined at all. The geography of it (they didn't realize it was right next to Kentucky), how beautiful it is, the amenities that exist here, and just the general spirit of the city. Cincinnati is very surprising.

Top image via YARD: YARD & Company was engaged to work with neighbors to develop a program that brought people together in a new way while powerfully redefining the western edge of a Fort Wayne neighborhood.

John Pattison is the Community Builder for Strong Towns. In this role, he works with advocates in hundreds of communities as they start and lead local Strong Towns groups called Local Conversations. John is the author of two books, most recently Slow Church (IVP), which takes inspiration from Slow Food and the other Slow movements to help faith communities reimagine how they live life together in the neighborhood. He also co-hosts The Membership, a podcast inspired by the life and work of Wendell Berry, the Kentucky farmer, writer, and activist. John and his family live in Silverton, Oregon. You can connect with him on Twitter at @johnepattison.

Want to start a Local Conversation, or implement the Strong Towns approach in your community? Email John.