The Congestion Con: How Bad Land Use and Transportation Decisions Go Hand-in-Hand

Steve Davis is the Director of Communications for Smart Growth America and Transportation for America. This guest post introduces a new report, The Congestion Con, published by Transportation for America.

Join us in a webinar on March 17th to learn more about the findings.

At 2 p.m. EST on Tuesday, March 17, you can hear from T4America director Beth Osborne and Strong Towns founder and president Charles Marohn as they discuss the findings from The Congestion Con.

In an expensive, decades-long effort to curb congestion in urban regions, our transportation agencies and elected leaders have overwhelmingly prioritized spending hundreds of billions of dollars to widen and build new highways. Yet this strategy has utterly failed to “solve” the problem at hand, and in many cases, has actually made it worse. The Congestion Con, a new report from our Transportation for America program, examines how and why, and in this post we look at how land use is right in the middle of it all.

This is the basic story from The Congestion Con: How more lanes and more money equals more traffic:

Between 1993 and 2017, we added 42 percent more freeway lane-miles in the largest 100 urbanized areas, which significantly outstripped the 32 percent growth in population in those regions over the same time period. So congestion and delay went down, right? No, it exploded—up by a staggering 144 percent, far outpacing population growth. Not everyone was building roads at the same rate, but the story was the same all over the country:

Among urban regions with moderate or high population growth, some cities saw their populations grow at a much faster rate than freeway lane-miles, and also faced significant increases in delay—no big surprise. At the same time, however, freeway lane-miles were expanded a roughly equivalent pace as population growth in cities like San Diego, CA and Nashville, TN yet they saw larger increases in delay: 175 percent for San Diego and 329 percent for Nashville. Meanwhile, lane-miles were added at more than three times the population growth rate in places like Pensacola, FL and Omaha, NE yet delay still increased by 233 percent and 231 percent, respectively. And delay increased by an astonishing 446 percent in Boise, ID, where population grew by 117 percent and lane-miles grew by 141 percent. …in Jackson, MS, population grew by a comparatively low 9 percent and the region expanded its freeways at seven times that rate, yet delay increased by 317 percent. Buffalo, NY’s population dropped by 12 percent, and the region still faced a 175 percent increase in delay.

We are spending billions of dollars to widen or expand roads and seeing nothing logical or helpful in return. And yet we are continuing to double down on a strategy that isn’t working.

It’s been an expensive gambit. If you read Repair Priorities back in 2019, you might remember that states alone spent more than $500 billion on highway capital investments in urbanized areas between 1993-2017—much of that on expansion projects. States are on the hook for maintenance, which makes these expansions major financial liabilities now and for years into the future—something you’re unlikely to hear trumpeted by the elected leader promoting the latest big widening project. For roads already in good condition, it still costs approximately $24,000 per year on average to maintain each lane-mile in a state of good repair. The price tag just to maintain what we’ve already got is staggering.

If the “solution” to congestion isn’t working and we’re producing more liabilities than we can ever possibly afford to maintain, why continue plowing billions of dollars into this tactic?

Somebody needs to call a “time-out.”

Why aren’t we reducing congestion and what does land use have to do with it?

The Congestion Con primarily looks at data on freeway lane-mile growth, but you can see the same issues at play on state and local roads, and it’s not always just the fault of our transportation agencies: land use is a primary driver. But bad transportation decisions begat bad land use decisions and vice versa, as we’ll explain momentarily.

A better question to ask than the headline above would be this: Why should a land-use and transportation system perfectly designed to generate maximum congestion ever be expected to reduce it? This is one of the fundamental truths about congestion that is yet so misunderstood. As the report quotes Chuck Marohn from Strong Towns, “we manufacture a flood” of congestion, and we do it on purpose. How?

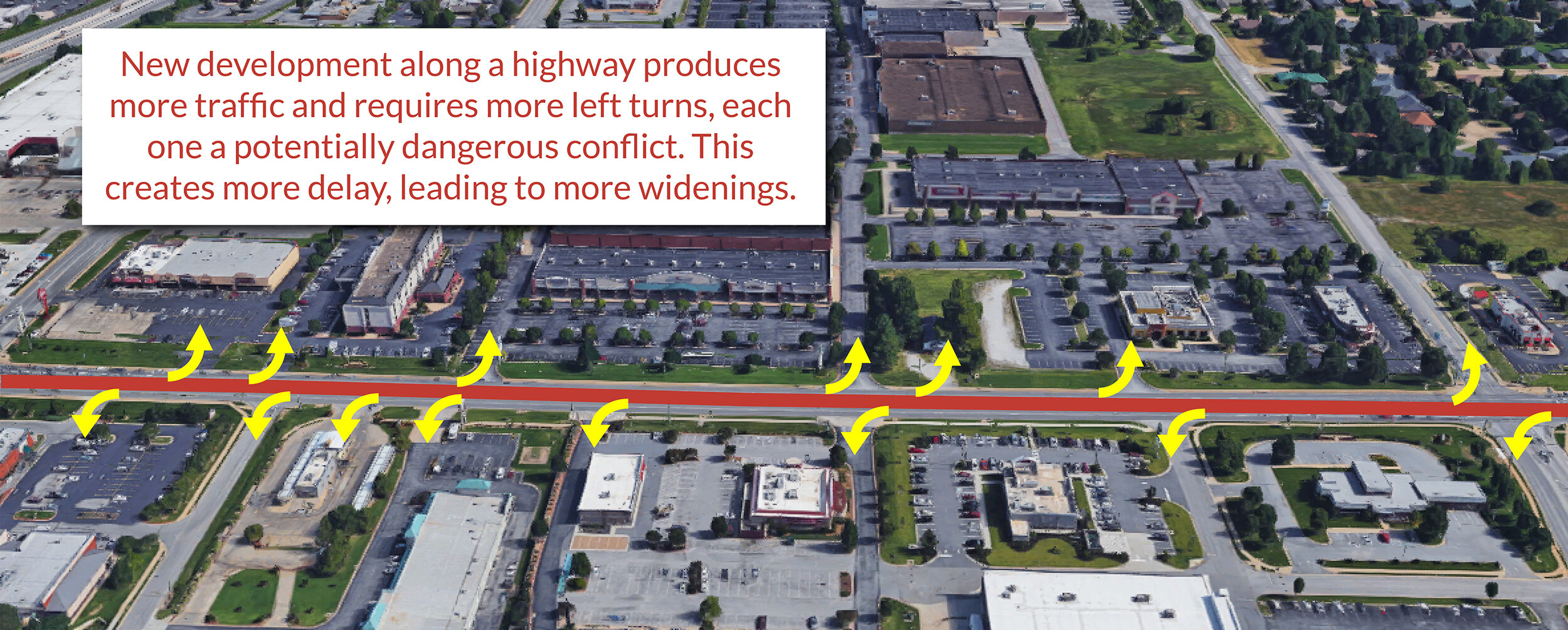

Here in the first graphic below is a pretty typical pattern of land use and transportation investment in most growing metro areas. There’s a state-owned road, and a community starts sprawling outward, adding new subdivisions and more development along the road.

When we let development sprawl like this, we create greater distances between housing and other destinations which forces people to take longer and longer trips on a handful of regional highways to fulfill almost all of their daily needs.

In this one frame above, there are 300 houses (with more clearly on the way) that create thousands of car trips every day on the same two-lane highway, which is the only way to reach regional job centers, retail, schools, and pretty much every single other daily destination. The frontage lots are likely zoned for commercial retail uses, so one day this highway will be filled with more new curb cuts requiring left turns, which eventually means signals, which will guarantee more delay.

Every single increment of new development here—every new subdivision, every new curb cut for a retail center—is virtually guaranteed to create more delay on that highway. By design. And when attempts are made to “solve” that congestion by widening the highway (the bad transportation decision), it just encourages and enables more similar development further out (the bad land-use decision), guaranteeing yet more delay through the corridor.

This vicious cycle is the reason we are spending billions on a “solution” that’s failing us and keeping millions stuck in traffic.

Travel a little to the west in that first image above, and you’ll find more development coming or built the exact same way—all designed to produce maximum congestion.

Every single day during rush hour, this highway is likely to get a little backed up due to delay. Have the calls already begun to widen it in order to “alleviate” all this congestion? And if the state goes through with such a project, after spending tens of millions of dollars to do it, what will happen next? The Congestion Con predicts the future thanks to years of examples:

Just a few short years after investing millions of dollars to expand the highway, traffic has increased enough that the road becomes congested again and travel speeds go back down, leaving people in the same position or worse off than they were before the expansion projects. Residents begin complaining about congestion, and elected leaders start touting a need to widen the road. The cycle starts over.

Is there a better alternative to emulate? There’s an obvious one just a few miles away from here near the center of this same medium-sized town: a network of connected streets that allows more people to generate far fewer trips, shorter trips, and can even eliminate trips altogether by walking, biking or chaining trips together.

A mix of destinations spread throughout a network of connected streets is a far more productive (and fiscally responsible) approach to managing congestion because it disperses trips, improves access, and allows for shorter trips and fewer trips total. We can’t “solve” congestion by only increasing supply (new roads or lanes). More supply will just get filled right up with new trips and new cars, a phenomenon known as induced demand:

The concept of induced demand has significant research backing it up. For example, one recent study by Kent Hymel of California State University of Northridge produced results suggesting that highway capacity expansion generates an exactly proportional increase in vehicle travel—a one percent increase in road capacity can produce a one percent increase in VMT. Hymel’s study also found that induced vehicle travel is expected to revert traffic speeds to levels pre-expansion in just five years.

Just compare the difference in this series of graphics showing how trips are accomplished in a different sprawling area of the same town compared to that compact street network where destinations are mixed throughout:

Addressing congestion without considering land use is like traveling to the moon without considering gravity.

We will never be able to widen our way out of congestion, and we need to stop wasting our money on trying.

We need to instead start thinking about improving access as a guiding principle. How many destinations can one quickly and easily reach by any mode of travel? The second gridded street network above is successful in part because access is high. Anyone who lives or works within view in that image can get to any jobs pictured by multiple routes. A good number of them could walk or bike or take a bus. Even if driving, their trip to every single job within view would be radically shorter than even the shortest trip from one of the above subdivisions to the nearest job center.

“It’s time to critically examine our assumptions about congestion and try something new. Something that doesn’t force people to travel longer distances and allows them to get to the things they need in or out of a car,” said T4America director Beth Osborne in today’s press release. “We focus too much on congestion yet have done nothing but make it worse.”

It’s time for an end to this “con.”

Reminder: Join Beth Osborne of T4America & Charles Marohn of Strong Towns on March 17 to hear more about the report findings and why we’re stuck in this vicious cycle.

Top image via Wikimedia Commons. All other images via T4America.

About the Author

Steve Davis is the Director of Communications for Smart Growth America and Transportation for America. Trained at the University of Georgia’s Grady School of Journalism & Mass Communication, he was an award-winning photographer at the Arkansas Democrat Gazette before following his passion for great places to Smart Growth America. He loves the challenge of figuring out how to turn the complicated policies and details of creating more smart, sustainable, lovable places into messages that resonate with a wide range of people. Steve lives in the Petworth neighborhood of Washington, DC with his wife and three children and loves his three-mile run or bike ride to work.