How Highways Finally Crushed Black Tulsa

Joe Cortright (Twitter: @CityObs) is a longtime Strong Towns contributor who runs the think tank City Observatory. This post first appeared in slightly different form on the City Observatory website, where you can find other articles, original research, and data-driven analysis of cities and the policies that shape them.

Last May 31 and June 1 marked the centennial of the Tulsa Race Massacre, in which hundreds of Black residents of Tulsa’s Greenwood neighborhood were brutally killed and the neighborhood itself leveled. Recent news stories have made more Americans aware of this tragic chapter of our history that unfolded in 1921: Greenwood’s residents were shot and beaten, their homes and businesses burned and their neighborhood bombed.

What’s less known is that despite the best efforts of the violent racists, they didn’t kill Greenwood. In fact, the neighborhood’s Black residents returned and rebuilt, in less than five years. The rapid rebuilding—done in spite of the obstacles put in its place by the City of Tulsa, and continued racial discrimination—drew praise for the neighborhood’s resilience. In 1926, W.E.B. Dubois wrote that “Black Tulsa is a happy city,“ saying:

Five little years ago, fire and blood and robbery leveled it to the ground. Scars are there, but the city is impudent and noisy. It believes in itself. Thank God for the grit of Black Tulsa.

Rebuilt and thriving Greenwood in North Tulsa, 1930s.

Greenwood’s heyday stretched into the 1950s, and even its moniker—”The Black Wall Street”—dates from this period.

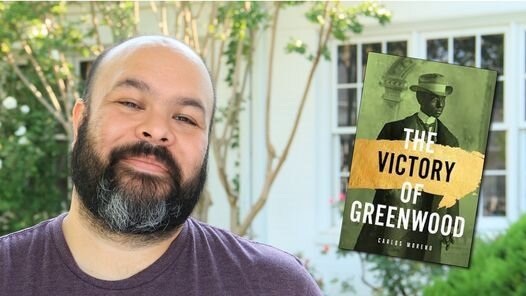

What finally killed Greenwood wasn’t an angry racist mob, it was the federally-funded interstate highway system. Coupled with urban renewal, highways built through North Tulsa’s Greenwood neighborhood in the late 1960s did what the Klan and white racists couldn’t do: demolish the and depopulate the place. That’s the key conclusion of a newly published book by Carlos Moreno, which chronicles the neighborhood’s destruction, rebirth, and ultimate demise at the hands of the highway builders. NBC News interviewed Moreno, and reported:

In his new book set to be released next week, “The Victory of Greenwood,” Moreno explores how the neighborhood had a second renaissance led by Black Tulsans after the massacre, rebuilding even bigger than before. It was not the bloodshed that eventually destroyed most of Greenwood, however; rather, it was this, he said, pointing to the spaghetti of interchanges to the south and the expressway that stretches north.

In an essay at Next City, Moreno explains:

What often gets erased from Greenwood’s history is its 45 years of prosperity after the massacre and the events that led to Greenwood’s second destruction: The Federal-Aid Highway Acts of 1965 and 1968. As early as 1957, Tulsa’s Comprehensive Plan included creating a ring road (locally dubbed the Inner-Dispersal Loop, or IDL); a tangle of four highways encircling the downtown area. The north (I-244) and east (U.S. 75) sections of the IDL were designed to replace the dense, diverse, mixed-use, mixed-income, pedestrian, and transit-oriented Greenwood and Kendall-Whittier neighborhoods.

As in so many other US cities, the construction of freeways was used to demolish, divide and isolate communities of color. President Biden acknowledged the federal government’s role in Greenwood’s decline in his proclamation of a Day of Remembrance:

And in later decades, Federal investment, including Federal highway construction, tore down and cut off parts of the community. The attack on Black families and Black wealth in Greenwood persisted across generations.

Carlos Moreno and his book, The Victory of Greenwood. Image via Happening Next.

At a community conversation sponsored by Tulsa Urbanists, Moreno summarized his research on the role of the 1921 race massacre and later highway building and urban renewal efforts in destroying Greenwood: “Greenwood looks the way it does today, not because of the massacre. It came back. And there’s a video footage of that. But North Tulsa/Greenwood look the way it does today because of the federal highway project, and because of urban renewal…”

And Tulsa continues to widen highways even as it refuses to discuss reparations for the destruction of Greenwood. Again, Moreno:

Somehow it’s okay for Tulsa to pay $36 million to repair one mile of road between 81st and 91st on Yale in South Tulsa, like that’s okay. We have no problems doing that. We just passed a road widening bill and every single citizen of Tulsa is paying a part of that $36 million. But somehow reparations for Greenwood is a non starter…

A hat tip to Next City for publishing Carlos Moreno’s synopsis of his book and Graham Lee Brewer of NBC News for his reporting on how the highway’s wounds still trouble Greenwood to this day.

It’s hard to imagine anything more hateful and horrific than the bloody attack on Greenwood in May, 1921. In the past century, that kind of violent overt racism has given way to a more subtle, more pernicious and more devastating kind of systemic or institutional racism—including in the form of highway construction.

Joe Cortright is President and principal economist of Impresa, a consulting firm specializing in regional economic analysis, innovation and industry clusters. Over the past two decades he has specialized in urban economies, developing the City Vitals framework with CEOs for Cities, and developing the city dividends concept.

Joe’s work casts a light on the role of knowledge-based industries in shaping regional economies. Prior to starting Impresa, Joe served for 12 years as the Executive Officer of the Oregon Legislature’s Trade and Economic Development Committee. When he’s not crunching data on cities, you’ll usually find him playing petanque, the French cousin of bocce.