Freeway Widening for Whomst?

This article was originally published on longtime Strong Towns contributor Joe Cortright’s blog, City Observatory. It is shared here with permission. All images for this piece were provided by the author.

The proposal to spend $5 billion to widen a five-mile stretch of I-5 between Portland and Vancouver is being marketed with a generous dose of equity washing. While it is branded the “Interstate Bridge Replacement,” or IBR, replacing the bridge is less than a quarter of the total cost; most of the expense involves plans to double the width of the freeway to handle more peak hour traffic. The project has gone to some lengths to characterize suburban Clark County as an increasingly diverse population to create the illusion that the freeway widening project is primarily about helping low- and moderate-income households and people of color travel through the region. A quick look at Census data shows these equity claims are simply false. Peak hour freeway travelers commuting from homes in Washington to jobs in Oregon are overwhelmingly wealthy and white compared to the region’s average resident.

What this project would do is widen—from six lanes to as many as 14 lanes—five miles of Interstate 5 between Portland and Vancouver. The principal reason for the project is a claim that traffic volumes on I-5 cause the road to be congested. But congestion is primarily a peak hour problem, and is caused by a large and largely unidirectional flow of daily commuter traffic. About 60,000 Clark County residents work at jobs in Oregon, and they commute across either the I-5 or I-205 bridges. Fewer than a third that many Oregonians work in Clark County, with the result being that the principal traffic tie-ups coincide with workers driving from Clark County in the morning, and back to Clark County in the evening. Plainly, this is a project that is justified largely on trying to provide additional capacity for these commuters. That being the case, who are they?

Census data show that the beneficiaries of the IBR project would overwhelmingly be whiter and higher income than the residents of the Portland metro area. As with most suburbs in the United States, Clark County’s residents, who are those most likely to use the IBR project, are statistically whiter and wealthier than the residents of the rest of the metropolitan area. In addition, the most regular users of the I-5 and I-205 bridges are much more likely to be white and higher income than the average Clark County resident. This is especially true of peak hour work commuting from Clark County Washington to jobs in Oregon, which is disproportionately composed of higher income, non-Hispanic white residents.

Peak Hour, Drive-Alone Commuters Are Overwhelmingly White and Wealthy

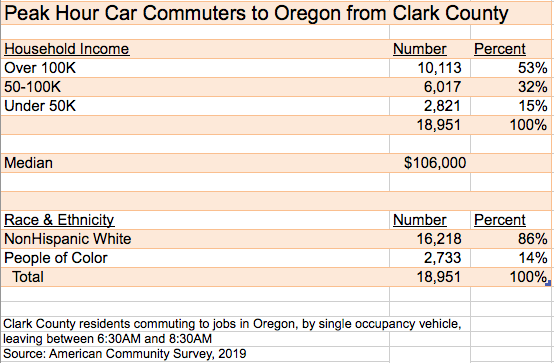

Data from the American Community Survey enable us to identify the demographic characteristics of peak hour, drive-alone commuters going from Clark County Washington to jobs in Oregon on a daily basis. Here are the demographics of the nearly 20,000 workers who drive themselves from Clark County to jobs in Oregon, and who leave their homes between 6:30 a.m. and 8:30 a.m. daily. Some 53 percent of peak-hour, drive-alone commuters from Clark County to Oregon jobs lived in households with annual incomes of more than $100,000. The median income of these peak hour drivers was $106,000 in 2019, well above the averages for Clark County and the region.

Fully 86 percent of the peak-hour, drive-along commuters from Clark County to Oregon jobs were non-Hispanic whites. Only about 14 percent of these peak hour drivers were persons of color. The racial/ethnic composition of these peak hour car commuters is far less diverse than that of Clark County, or the region. Clark County workers who work in Clark County are about 50 percent more likely to be people of color than those who commute to jobs in Oregon.

Clark County is Whiter and Wealthier than the Region and Portland

Suburban Clark County, Washington, is whiter and wealthier than the rest of the Portland metropolitan area, and the City of Portland. Clark County may be more racially and ethnically diverse than it once was, but so is the entire nation. And it’s still disproportionately whiter and wealthier than the rest of the region. Only about 23 percent of its residents are people of color, compared to about 38 percent for the region as a whole, and about 30 percent for Portland, according to the 2019 American Community Survey. Clark County’s median household income of $80,500 is higher than for the region ($78,400) and for the City of Portland ($76,200).

Few Low-Income Workers and Workers of Color Commute to Oregon from Clark County

Not only is Clark County less diverse than the rest of the Portland region, only a small fraction of its low-income workers and workers of color commute to jobs in Oregon at the peak hour. More than ten times as many low-income workers and workers of color who live in Clark County work at jobs in Clark County than commute to jobs in Oregon. About 38,000 Clark County workers in households with incomes of $50,000 or less work at jobs in Clark County; only about 2,800 are peak-hour, drive-alone commuters to jobs in Oregon. About 31,000 Clark County workers of color work at jobs in Clark County. If we’re concerned about addressing the transportation needs of low-income workers and workers of color in Clark County, we should probably focus our attention on the vast majority of them who are working at jobs in the county, not the comparatively small number commuting to Oregon.

Middle- and Upper-Income Households Are Far More Likely to Commute to Jobs in Oregon

In general, for Clark County residents, the higher your income, the more likely you are to commute to a job in Oregon. Only about one in five workers in households with incomes less than $40,000 in Clark County commute to jobs in Oregon. About 30 percent of workers in middle- and upper-income families in Clark County commute to Oregon jobs, meaning that these higher income households are about 50 percent more likely to commute to jobs in Oregon than lower-income households.

Data for this post is from 2019 American Community Survey, via the indispensable University of Minnesota IPUMS project.

Joe Cortright is President and principal economist of Impresa, a consulting firm specializing in regional economic analysis, innovation and industry clusters. Over the past two decades he has specialized in urban economies, developing the City Vitals framework with CEOs for Cities, and developing the city dividends concept.

Joe’s work casts a light on the role of knowledge-based industries in shaping regional economies. Prior to starting Impresa, Joe served for 12 years as the Executive Officer of the Oregon Legislature’s Trade and Economic Development Committee. When he’s not crunching data on cities, you’ll usually find him playing petanque, the French cousin of bocce.

Car companies have been talking about making cars a third place for years, and the concept has been engrained in North American culture for even longer. But can cars actually function as a third place? More importantly, should they?