Seems to Me That "Maybe" Pretty Much Always Means "No"

This historic house once belonged to the Janovich family, a fishing family who donated their purse seiner as a centerpiece for our history museum. The two small houses behind it were likely built to house crew members when they were working in town. Because of our zoning laws, this practical way of supporting local businesses is nearly impossible to do today.

The justification for zoning by land use has always been to protect homes from the negative impacts of industrial activity. Over time, we have greatly reduced both the number of factories in North America and the noise and pollution they produce, but the majority of people still believe their homes—and home values—will be adversely affected if uses are not regulated by geographical zones.

Zoning by land use provides homeowners with a sense of security, but it often closes the door on innovation and bottom-up investment. Along with restrictions on the number of housing units and inflated off-street parking requirements, land use requirements that segregate uses frequently reduce access, contribute to dependence on private motor vehicles, and thereby diminish residents' quality of life and the ability of governments to meet their obligations.

Some urbanists have made the case that the public would be better served by form-based codes regulating height, setbacks, and lot coverage; but allowing people to use their land as they see fit, as long as they otherwise follow the law.

These urbanist arguments, along with examples of thriving places that have adopted form-based codes, may eventually sway public opinion. But this would be a radical departure from the way things are done in most places and I doubt it will happen anytime soon.

In the meantime, I believe we should focus on adjusting our current use-based codes to encourage more productive investments in our places.

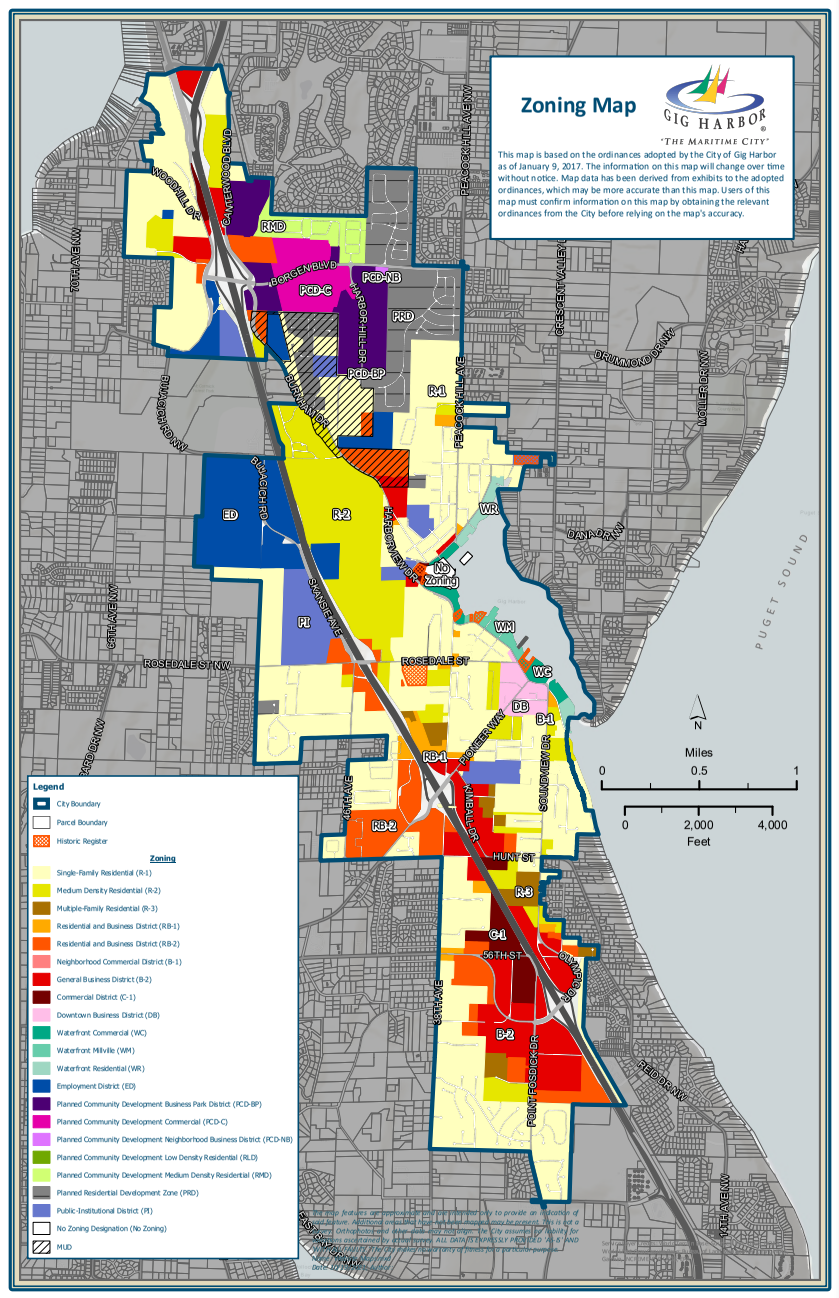

To that end, I’m going to walk you through the zoning code in my 12,000-person town of Gig Harbor, Washington (a 42-minute drive away from bustling Seattle). I have suggestions for minor shifts in policy here in my town, ideas that might enable it to evolve incrementally, and in turn be stronger and more resilient.

Gig Harbor’s zoning map. Click to view full-sized version.

What's in Your Code?

In Gig Harbor, our Land Use Matrix shows a table of all the city's planning zones (there are 20 of them within our small city of six square miles) against all defined uses (69 of those). The definitions section is needed to unravel less straightforward uses, like levels of restaurants or lodging. Zones can be found on the zoning map. The "P"s in the intersection of use and zone indicate the use is allowed in the zone. The dashes mean that it is not.

If the use and a zone intersection shows a "C,” the use is allowed conditionally. Procedures to be considered for approval—a complete application by the applicant, a report by planning staff with a recommendation for the hearings examiner, and a formal hearing—are described in various sections of the code. Applicants can refer to the city's comprehensive plan to convince the judge that their intended use fits into the objectives of the district they hope to operate within, but the code itself does not detail all criteria taken into account when determining whether a conditional use will be permitted. Clicking through the links outlining the conditional use permitting process, it is clear that approval of a conditional use adds significant time, money, and uncertainty to potential development.

The stated intent of conditional uses is that "Certain uses, because of their unusual size, infrequent occurrence, special requirements, possible safety hazards or detrimental effect on surrounding properties" cannot be allowed outright and must be examined on a case-by-case basis. It would be hard to argue that is not appropriate for some building types—say, hospitals, which are by definition large and uncommon. But in the case of small projects, such as accessory dwelling units, or using a house or part of a house as a short-term rental (both conditional uses in many places in my city), the code is being misused.

For these less unique buildings, elected officials, planning commission, citizens and staff should be able to determine what is needed to make a project acceptable within a zone and a review of whether conditions are met should be by staff, rather than by an arduous process requiring a public hearing for each instance.

Those in favor of broad use of conditional use zoning may advocate for being extra careful before allowing projects that might deviate even slightly from the norm to move forward. Conducting the hearing allows all those who might be affected by it to be informed of it and have their say. While that may be true, this benefit should be weighed against the drawbacks of applying these added layers of red tape and the inherent unfairness of ambiguous laws.

These apartments over a flower shop that was once a gas station in our historic downtown are a permitted use. Our historic downtown is the most beloved part of our city, so why don't we allow, by right, residential above retail in other business and commercial zones?

For Whom Does Maybe Mean No?

The most detrimental consequence of this extra caution is that it discourages some of the best projects that can happen in place and privileges some of the worst. Regardless of their size, projects need to generate enough revenue to offset costs. R. John Anderson's famous line, "if you can't get the rent, you can't build the building," is worth repeating (there are videos of him making whole rooms of aspiring developers do just that). Costs include those incurred before a building permit is even issued; these initial costs are not trivial and they are increased when permission for an intended use hinges upon a set of nebulous qualifications.

Small developers, that ”swarm” we would like to unleash in the Strong Towns approach, are most encumbered by the extra resources required to get special permissions. They are wise to choose to invest where the pathway to approval is clear. Conditional uses have all the hazards of projects that require variances and for small developers, that often means giving the project a pass. (See Johnny Sanphillippo's cautionary tale of a building he bought and spent a great deal of energy trying to develop.)

To the dismay of residents, my small city continues to grow in ways that make it worse. I've written about our "bad party" and Jeff Siegler took an even harsher view in a post titled “Hating the New Neighbors.” National developers are well positioned to absorb the delays and the expense of hiring experts needed to emerge triumphant from a prolonged, tangled zoning battle. We can see the generic housing developments and big box stores that extract wealth and leave long-term liabilities for those who stay behind. Less apparent is the lost potential of projects that never come to be because small developers, often locals, are deterred by the risks of investing where getting permission is uncertain.

The form of this "plex" building respects rules about lot coverage, setbacks, and height restrictions. After it was built, the land its sits on was zoned R-1, low density residential. It could not be built under current zoning.

How Do We Get from "Conditional Use" to "Allowed by Right"?

Conditional uses are a part of the zoning code that most people do not discover until they want to build something or make a change to the way their property is being used. Many property owners near me were unaware that Airbnbs are only allowed conditionally; a hearing was held to give permission to one and the city council enacted a six-month emergency moratorium on accepting other applications for this conditional use. Some of them have banded together to propose a set of conditions that they are willing to abide by so they can be granted permission to operate short-term rentals without applying for a conditional use permit. They will be heard by the planning commission later this month.

The movement to normalize short term rentals is being led by property owners who stand to profit from them. Accessory dwelling units, "plexes," and other multi-family housing have no such champions in my town at this time. Still, it will be interesting to see what sort of compromises may be reached and look to that process as a model for removing some of the barriers to bringing more varied and affordable housing, built by smaller developers, to our city.

Zoning's nefarious past of imposing laws that prevented those deemed to be inferior from living in desirable places should give us reason to be wary of the control that zoning bestows upon people in power. Requiring a public hearing in order to allow an accessory dwelling unit seems to me to be extending an invitation to those who seek to block even the most gentle, incremental changes. I hope that citizens and elected officials will open their eyes to the small changes that can be made to our code, right now, to get more projects that make us stronger built.

(All images for this piece were provided by the author, unless otherwise noted.)

Dive deeper through our 2022 Local-Motive Tour stop, “4 Quick Zoning Code Reforms for a Strong Town”!

In this one-hour webinar, you’ll learn four zoning code reforms that you can act on immediately, and which will dramatically unlock potential for prosperity in your city.

Marlene Druker is an architect and Strong Towns advocate in Gig Harbor, Washington. Her professional website is under construction at marlenedarchitect.com and her local advocacy page is Grassroots for a Healthy Harbor. Many of her volunteer activities involve sharing her love of cycling. In addition to leading rides for Cascade Bicycle Club, where she is tour leader for their Gig Harbor Tour Lite, she is founder of the facebook group Bike - Gig Harbor! and the Greater Gig Harbor Foundation's Rattle Dem Bones Halloween Bike Ride and Costume Contest.

What began as a quiet act of care—building benches where none existed—just got the City of Richmond’s official blessing.